The Fall of Fort Henry and the Changing of Confederate Strategy

Fort Donelson has “Unconditional Surrender” Grant. It has an early morning Confederate attack, a breakout by Nathan Bedford Forrest and, in short, the stuff that makes good history. But from this outsider’s perspective looking in on the Western Theater, I believe (and have believed for some time) that Fort Henry, in the grand scheme of things, gets the proverbial short end of the stick.

No, it does not last as long as the operations at Fort Donelson. It does not have the casualties that Donelson witnesses. It does, however, have an impact on Confederate strategy. In fact, the Confederacy repeatedly fell back on that strategy throughout the remainder of the war.

At the war’s onset, Commander in Chief of the Confederate States of America Jefferson Davis and his subordinates settled on the idea of defending all borders of the fledgling nation, which encompassed 750,000 square miles of territory. Historian James McPherson calls this plan the “dispersed defense.” Early in the war, this strategy won political points for Davis and his administration by protecting many points on the periphery of the Confederacy. However, it also made things difficult for the Southern commanders vainly attempting to hold vast swaths of land with minimal manpower. Fort Henry’s fall on February 6, 1862, changed all of that.

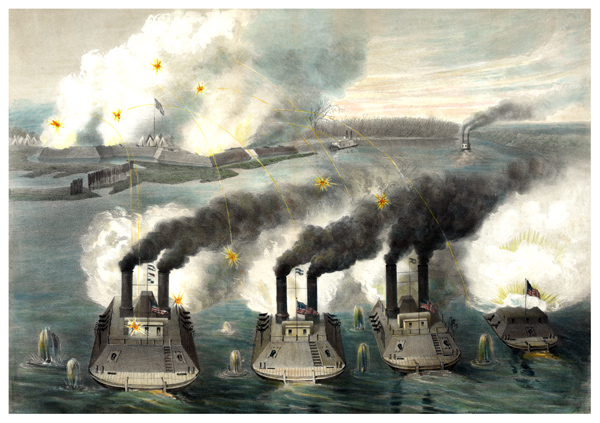

The capture of Fort Henry by Union forces opened much of the Tennessee River and its banks to Northern soldiers. Demonstrating the river’s dagger-like course through the heart of western Tennessee, a cadre of Federal gunboats proceeded along the river in the wake of Fort Henry’s fall all the way into northern Mississippi and Alabama. While the raid ultimately failed to destroy several larger objectives, it none the less proved the Northern hypothesis that the Confederacy was a hollow shell–crack its outer layer and nothing lay in the interior to stop Federal advances.

On February 8, Jefferson Davis began veering the Confederacy away from its dispersed defense. Davis could no longer cave to political pressures while Union forces carved up the Confederacy’s boundary. Accordingly, he ordered Southern soldiers to make their way to Tennessee. Mansfield Lovell’s soldiers began their trek from New Orleans while Braxton Bragg left Pensacola en route for the Volunteer State. Confederate gunboats protecting New Orleans also sailed up the Mississippi River, eventually exposing the Crescent City to Union hands.

While stripping the Confederacy of its exterior defenses, forces began to concentrate in northern Mississippi, poised to strike back the Federal thrust through western Tennessee. It was a new take on Southern strategy, gathering forces at select points to attack the enemy when advantage seemed in the Rebels’ favor. The Confederacy altered its strategy to the offensive-defensive as a way to preserve, as best as it could, the exterior of its hollow shell. This strategy manifested itself first at Shiloh in early April 1862 and later at places like Antietam, Perryville, and Gettysburg.

One small fort on the Tennessee River and its capture by the forces of Ulysses S. Grant and Andrew Foote in February 1862 changed the shape, but not the course, of the Civil War for the next three years.

I think it is important to recognize why Davis dispersed his forces. Explicitly, his decision to create the departmental system was directly related to fears of servile insurrection. Through out the the war in the West, tens of thousands of men were kept away from the front essentially as a slave patrol. The conceit that non-slaveholders would be willing to “die in the last ditch to protect the rights of their more fortunate neighbors” had evaporated at once. Given half a chance, even the most privileged of slaves would self liberate. As it ever was, the very real threat of heartless iron fisted violence kept the slave population in line. It was the necessity of keeping the servile population under control that distorted Davis’ strategy throughout the war.

It is also useful to point out that Fort Henry was underwater for a reason. The Confederate command structure under A. S. Johnston had behaved like a carload of squabbling small girls on a long car trip. (I speak as a father, grandfather & great grandfather of girls.) his inability to bring them under control was just one example of his lack of executive ability. The hubristic, ego driven incompetence of Johnston’s commanders cannot be exaggerated. The adult level, collegial relationship between Grant & Foote could not have been more different.

The essay’s assertion that Johnston’s concentration in Northerm Mississippi was part of a grand strategy could not be further from the truth. As one of his staff officers asserted, Johnston’s muddled, mindless leadership put him in danger of being declared an imbecile & confined for his own protection. As events would make glaringly obvious, there was no grand United Confederate strategy for prosecuting the war.

The essay is right that, after the fall of Fort Henry, the Confederacy (in the West) was on its heels, and could only react to what the Federals were doing. Mr. Cole’s comments about the shortcomings of A.S. Johnston as a commander are equally spot-on.

Great article Kevin!

Thanks for sparking interest in the Story of Fort Henry. Other elements to the story: Fort Columbus was too strong for Union direct assault. 13-inch mortars were late to arrive. Confederate faith in torpedoes was misplaced. Fort Heiman was incomplete. Once-in-40 year flood of Tennessee River surprised a few folks. Flag-officer Foote was certain his gunboats could do the job at Fort Henry. Phelp’s Raid (planned before the attack on Fort Henry) destroyed the locally available stock of torpedoes; captured nearly-complete CSS Eastport; destroyed every steamer on the Tennessee River (except two); identified “pockets of Union support” along the river; disabled the M C & L R.R. Bridge. The subsequent capture by U.S. Grant of Fort Donelson was the final element that “turned” Fort Columbus (and allowed the Union Navy to begin working south down the Mississippi River.)

As for Confederate strategy: the unanticipated movement against Pittsburg Landing in April 1862 was contemplated to reverse the tide in Tennessee (and with luck, lead to pushing Union forces all the way north to the Ohio River.)

I appreciate your response. You are obviously conversant with the campaign. I have come to the conclusion that Shiloh had a great deal to do with A.S. Johnston flailing around for some way to salvage his reputation than anything else. He was, with good reason, being excoriated in the Southern press. Imbecile was one of the restrained epithets being flung his way. Allowing Beauregard to write up his own battle plan & issue orders that Johnston clearly did not understand was just another, final, example of his lack of executive ability.

“Since it was obvious they were going to lose, why didn’t the Confederacy just pack it in after the surrender of Fort Donelson?” Because in February 1862, it was not obvious to anyone what would be the outcome of the War (Rebellion). 1861 had been a year of Rebel successes on the battlefield. And the Measure of Ultimate Success (Rebel) was established as Victory due force of arms; or international recognition of the Confederate States as a viable nation and Government; OR persuading the People of the United States to give up the fight. Despite setbacks at Mill Springs and Fort Henry and Fort Donelson, the South anticipated “things would come good again” …as they did with launch of CSS Virginia; holding onto Vicksburg through 1862; the delaying action at Corinth April/ May 1862; holding off McClellan (followed by Bragg’s offensive into Kentucky) and Victory at Second Manassas. Meanwhile, efforts to perfect torpedoes continued. And efforts to acquire Commerce Raiders pressed ahead. Time and delay counted for much, and prolonging the conflict favored the Confederacy, because as long as the struggle continued, “something” could happen that resulted in Recognition, or the North tiring of the endless struggle (and suing for Peace.)

“There is no failure, until one gives up the struggle.”

Another interesting aspect regarding the flood is that the river level was still high in early April. That may have played a role in the federal gunboats being able to shell the Confederate camps from the area of Dill Branch on April 6-7.