A Radical Gettysburg Address

President Abraham Lincoln’s two-minute remarks during the dedication of the Soldiers’ Cemetery at Gettysburg on November 19, 1863 may be the most heralded words ever delivered in the English language. For nearly 160 years, the legacy and mythology surrounding that brief address consigned the orations of the two principal speakers of that day, Edward Everett and Charles Anderson, to historical obscurity. Everett’s two-hour address was so instrumental that he convinced organizers to postpone the entire ceremony for almost thirty days so that he could prepare properly. Anderson’s forty-minute effort, which concluded the day’s events, never appeared in print until it was rediscovered in a cardboard box in Wyoming in the twenty-first century.[1]

David Wills invited Lincoln to speak just seventeen days before the dedication, realizing that the president’s enormous responsibilities in the midst of civil war might preclude his attendance. Lincoln finally committed just four days before the event. At this point, the president began composing what would become his most famous speech.

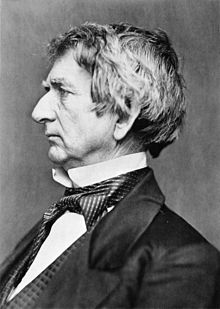

Many historians eschew “what if” questions; however, there was a distinct possibility that events might have caused Lincoln to cancel his Gettysburg trip at the last minute. If that had happened, the president’s most trusted advisor, Secretary of State William H. Seward, was prepared to step in and deliver what Wills requested as a “few appropriate remarks.” Although Seward was an unflinching supporter of Lincoln’s policies, had his remarks graced the platform that late November day, rather than Lincoln’s immortal words, historians would have remembered the dedication much differently.[2]

Seward was born into a slaveholding family in rural New York, so it is ironic that he became known as one of the strongest advocates for racial justice among leading politicians of the nineteenth century. Most politicians like Seward were not free to express their anti-slavery positions fully and openly, as extreme positions on such sensitive issues often meant career suicide; yet Seward’s actions and some of his statements belied strong sympathy with abolitionists. He and his wife sheltered escaped slaves in their home in Auburn, New York. When defending a black man an 1846 trial, Seward made a remarkable assertion of racial equality: “In spite of human pride, he is still your brother, and mine, in form and color accepted and approved by his Father, and yours, and mine, and bears equality with us the proudest inheritance of our race—the image of our maker.”

Seward cemented his reputation as a radical despite his efforts to be seen as moderately anti-slavery in an infamous 1858 speech in Rochester, New York. He described slavery as “intolerable, unjust, and inhuman” and suggested that an “irrepressible conflict” existed in America that could only result in the United States becoming either a slaveholding or a free labor society in its entirety. This controversy had to be resolved, in Seward’s view, “even at the cost of civil war.” That speech may have cost him the Republican Party nomination for president in 1860, as Lincoln was much more adept at opposing the expansion of slavery in the territories while assuring slaveholders that he had no intention to interfere with their peculiar institution where it already existed.[3]

Despite the fact that the Emancipation Proclamation had been in effect for nearly a year when Lincoln and Seward journeyed to Gettysburg, the president took great pains to rise above partisanship and sectionalism is his address and instead evoked his vision of reunion with reconciliation. Although his administration had shifted the focus of the war from merely preserving the Federal Union to destroying slavery in the rebellious states, his language extolling “a new birth of freedom” was not incendiary, never mentioned the Confederacy, and left some room for interpretation. Seward’s speech, in contrast, was direct and provocative.

Texts of Seward’s planned remarks, along with Everett’s long soliloquy, were distributed to the press in advance of the dedication. The night before the event, crowds of serenading citizens gathered to implore the president to speak. He politely declined, defusing the crowd with his typical humor. Undeterred, the well-wishers marched to Robert Harper’s home, where Seward was staying. Lincoln’s top diplomat needed no cajoling and was more than pleased to deliver his short address, as he knew it would be correctly reported in the loyal newspapers afterwards.

Seward began by remarking that, in light of his reputation as an outspoken anti-slavery man, he had never been asked to speak so close to the border with Maryland. Some observers thought that perhaps Seward was confused and believed that Gettysburg was in Maryland or below the Mason-Dixon line. He then launched into a brief, but scathing rebuke of slavery as the proximate cause of the fratricide that shocked even Republican newspaper reporters. One claimed that Seward had “made a speech so radical that Montgomery Blair must have shaken in his boots.”[4]

The secretary reminded his listeners that he had been warning them for forty years that “slavery was opening before this people a graveyard that was to be filled with brothers falling in mutual political combat.” Seward claimed he had done his best to help settle the question within the confines of the Constitution and avoid catastrophe. He described dead rebel soldiers as “misguided” and lamented that the U.S. Army had to “consign them to their last resting place with pity for their errors.” “We will mourn together for the evil wrought by this rebellion,” he assured the crowd.

Seward thanked his God that the present strife would culminate in the end of slavery. “When that cause is removed, simply by the operation of abolishing it as the origin, an agent of the treason,” he predicted, only then would the nation heal and “feel that we are not enemies but that we are friends and brothers.” These words would be paraphrased later in Lincoln’s second inaugural address. Late that evening, Lincoln visited Seward to review the draft of his own address, perhaps confident in sticking to a higher rhetorical plane, as the secretary had already launched his verbal salvos at an enemy who, after all, remained to be defeated on the battlefield. The president would leave the task of rousing the audience back to an aggressive pursuit of his war agenda to Anderson, whose fiery speech the afternoon of November 19 made no bones about what Lincoln had obliquely referred to as “the great task remaining.”

Seward’s speech did not dwell solely on the treason of the rebels or the necessary extinction of slavery. He also took time to reinforce principles of republican governance that echo forcefully in 2021 in the aftermath of yet another contentious presidential election that helped spawn an ugly, violent insurrection this past January 6th. “Let us remember that we owe it to our country and to mankind that this war shall have as its conclusion the establishing of the principle of democratic government — the simple principle that whatever party, whatever portion of the community, prevails by Constitutional suffrage in an election, that party is to be respected and maintained in power until it shall give place, on another trial and another verdict, to a different portion of the people. If you do not do this, you are drifting at once and irresistibly to the very verge of universal, cheerless and hopeless anarchy.”

Lincoln’s brief but brilliant address became secular scripture, destined to be remembered for all time, while the efforts of Seward and other speakers faded from historical memory. It is useful to recall all of the speeches of November 18 and 19, 1863 in context to gain a better understanding of this unusual dedication in the midst of the most violent, radical revolution of the nineteenth century world.

David T. Dixon is the author of The Lost Gettysburg Address: Charles Anderson’s Civil War Odyssey (2015). His website, “B-List History,” may be accessed at www.davidtdixon.com.

Notes:

[1] For the text of Seward’s and Everett’s Speeches at Gettysburg, see the official Report of the Select Committee Relative to the Soldiers’ National Cemetery (Harrisburg, Pa.: Singerly and Myers, 1864), 72 – 3, 81 – 108. For the text of Anderson’s speech, see David T. Dixon, The Lost Gettysburg Address: Charles Anderson’s Civil War Odyssey (Santa Barbara, Ca.: B-List History, 2015), 193 – 216.

[2] The best reference for understanding both Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address and the political context and nature of the dedication is Martin P. Johnson, Writing the Gettysburg Address (Lawrence, Ks.: Univ. Press of Kansas, 2013).

[3] A comprehensive treatment of Seward’s life and political career is Walter Stahr, Seward: Lincoln’s Indispensable Man (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2012).

[4] Johnson, Writing the Gettysburg Address, 92 – 5.

” yet another contentious presidential election that helped spawn an ugly, violent insurrection this past January 6th” I was with you until there. How could you transfigure a peaceful demonstration of earnest minds at the U.S. Capitol, the invitation of the protestors INTO the CAPITAL by the Capital Police, so long as it was kept peaceful, to the anarchist, Marxist mongrels occupying and destroying private property and attempting to eradicate statutes of the VERY HISTORY which presumably you do not want repeated? Entire city sections, for weeks, were violently occupied, wrecking violent havoc and death in multiple locations in the U.S.?

I agree…….there was no insurrection……maybe trespassing. A great article ruined by bringing fake news into the discussion. The real insurrection took place in many American cities where there was real destruction and looting.

Great post!

For Seward, slavery was intolerable because it kept blacks in the US: “The negro is a foreign and feeble element, a pitiful exotic unnecessarily transplanted into our field, and which it is unprofitable to cultivate.” To which he would add: “The white man needs the whole continent.”

Regarding Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, here is one of the few objective analysis:

“The Gettysburg speech is at once the shortest and the most famous oration in American history…

But let us not forget that it is oratory, not logic; beauty, not sense. Think of the argument in it! Put it into the cold words of everyday! The doctrine is simply this: that the Union soldiers who died at Gettysburg sacrificed their lives to the cause of self-determination — ‘that government of the people, by the people, for the people,’ should not perish from the earth. It is difficult to imagine anything more untrue. The Union soldiers in that battle actually fought against self-determination; it was the Confederates who fought for the right of their people to govern themselves. What was the practical effect of the battle of Gettysburg? What else than the destruction of the old sovereignty of the States, i. e., of the people of the States? The Confederates went into battle an absolutely free people; they came out with their freedom subject to the supervision and vote of the rest of the country—and for nearly twenty years that vote was so effective that they enjoyed scarcely any freedom at all. Am I the first American to note the fundamental nonsensicality of the Gettysburg address? If so, I plead my aesthetic joy in it in amelioration of the sacrilege.”

By M.L. Mencken, regarded as one of the most influential American writers of the first half of the 20th century

Yes it is a fact that many abolitionists, despite their moral opposition to slavery, were also white supremacists incapable of imagining a society where blacks and white coexisted as equal citizens. These two positions seem conflicting to our ears but they were distinctly different issues.

Mencken was more controversial than influential. He was an atheist, a racist, an anti-Semite and–shocker–steadfastly against any form of representative government. Read his Diaries published late last century–they say it all. They reveal him for what he was: a faux-intellectual-elitist-fascist. Most people who admired his writing were shocked when they were published. He has his place in American journalism, but he’s a footnote in American history, for good reason–just about everything he believed in was anti-American. I’ll take Lincoln’s perspective on democracy any day over a nihilistic fascist and thankfully so do the majority of Americans.

Lincoln’s pick for Sec. Of State is fascinating because of how Seward was the favorite in 1860 for sometime before Lincoln’s come from behind finish at the convention. Lincoln would then have his biggest rival part of his administration. Secretary of State had been a stepping stone to the President in the early days of the Republic. He would never gain the post and yet Seward’s handling of overseas diplomacy during the war was shrewd an critical in keeping Europe out of the conflict, eventhough it could be argued that Europe was never going to get involved because they would rather see the representative government established in the states crash and burn.

It could also be argued that Seward would be an early visionary of America’s Imperialist aims in the later part of the 19th century. This would cause a dilemma in the American populace as individuals like Andrew Carnegie and Mark Twain would form an anti-Imperialist league to sway Americans from such ventures. “Seward’s Folly”, I don’t feel, is viewd in the same light as it was back in his time. I think it could be said that Seward was one of the most significant Secretary of States in the 19th century and a major contributor to the direction of America in years to come. This would eventually lead to establishing America as a major player in geopolitics that it still maintains today.