The Myth of Mrs. Bixby’s Letter

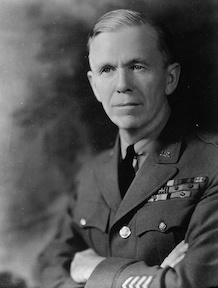

One of my favorite movie scenes of all time comes from Saving Private Ryan when Gen. George Marshall, informed about the deaths of three brothers, tells his staff that they’re going to send a special mission to retrieve a fourth, surviving brother. The staff protests, but Marshall will have none of it. Director Steven Spielberg has already shown the audience the reaction of the boys’ mother when the “I regret to inform you” telegraphs pulls up in her driveway, so we know the emotional stakes. Marshall, not actually privy to the scene, surely has it well in mind, though. Rather than issue orders to his staff, he instead pulls from a desk drawer a letter President Abraham Lincoln wrote to a similar mother some eighty years earlier.

The “letter to Mrs. Bixby,” well known in Lincoln circles, became instantly famous to the American public. It’s little wonder. Actor Harve Presnell delivers a reading of the letter with poignant gravitas—a letter so familiar to the character that Marshall actually stops reading it and instead recites it. Not until the end does he reveal the letter’s authorship, turning Abraham Lincoln into a mic drop. That settles the matter.

The scene is so powerful that moviegoers want the story to be true—and in fact, when Lincoln originally wrote the letter, he believed it to be so. But as with so many great stories in history, there’s more to the story of the Bixby’s letter.

Let’s start with the letter itself, which is a magnificent little piece of writing, worth a moment to read:

Executive Mansion,

Washington, Nov. 21, 1864.

Dear Madam,—

I have been shown in the files of the War Department a statement of the Adjutant General of Massachusetts that you are the mother of five sons who have died gloriously on the field of battle.

I feel how weak and fruitless must be any word of mine which should attempt to beguile you from the grief of a loss so overwhelming. But I cannot refrain from tendering you the consolation that may be found in the thanks of the Republic they died to save.

I pray that our Heavenly Father may assuage the anguish of your bereavement, and leave you only the cherished memory of the loved and lost, and the solemn pride that must be yours to have laid so costly a sacrifice upon the altar of freedom.

Yours, very sincerely and respectfully,

A. Lincoln

Much as he had in the Gettysburg Address, Lincoln admits that words can never live up to the monumental effort of compensating for death. But there’s an especial poignancy to the letter because Lincoln had, by this time, lost two sons of his own (Edward in 1850 and Willie in 1862). The letter is not just the commander in chief writing to the mother of five lost soldiers but one grieving parent reaching out to another.

The letter’s recipient, Lydia Parker Bixby, a widow, lived in Boston. Lincoln had been alerted to her situation by Massachusetts Governor John Albion Andrew, who asked Lincoln if he might send a letter of condolence. Lincoln did, and it arrived in Andrew’s office on November 25. Andrew not only had the letter delivered to Mrs. Bixby, but he sent copies to the Boston Evening Transcript and the Boston Evening Traveller, which both printed the letter in that day’s editions.

Unfortunately, the whole episode, as tragic as it sounded, was premised on inaccurate information compiled by the state Adjutant General’s office. Of Mrs. Bixby’s five sons:

- One deserted the army

- One was honorably discharged

- One deserted or died a POW

- Two sons died in battle, Charles and Oliver

And here’s where the story really caught my eye. The two Bixby sons killed during the war both had local connections to the battlefields around Fredericksburg, where I live.

The first, 22-year-old Sgt. Charles Bixby, had enlisted in the first hot summer of the war on July 18, 1861. He mustered into Company D of the 20th Massachusetts, “The Harvard Regiment.” The 20th Massachusetts had a particularly rough day at the battle of Ball’s Bluff on October 21, 1861, and they later saw action with the Army of the Potomac in its 1862 campaigns. Bixby was among the men who saw action along Hawke Street on December 11, 1862, at the battle of Fredericksburg.

In the spring, when Joe Hooker mobilized the army for the Chancellorsville campaign, the 20th Massachusetts was part of John Gibbon’s II Corps division, detached from the rest of the corps for action with John Sedgwick’s wing of the army. During the May 3, 1863, battle of Second Fredericksburg, Gibbon’s two brigades attacked north of the city but repulsed along a canal by the brigade of Confederate Brig. Gen. Cadmus Wilcox. Sgt. Bixby was killed during the fighting.

The second Bixby brother to die in the war was Pvt. Oliver Cromwell Bixby. Oliver enlisted on February 26, 1864, just a few days after his 36th birthday. He’d sat out the early years of the war and didn’t need to sign up. He mustered into Company E of the 58th Massachusetts, which was assigned to Col. Zenas Bliss’s brigade of Brig. Gen. Robert Potter’s division in Ambrose Burnside’s IX Corps.

On May 12, much of Burnside’s corps advanced against the east face of the Mule Shoe in a morning attack. Potter’s division spent the previous evening moving into position, which put the 58th Massachusetts right on the property that is now Stevenson Ridge, owned by my wife’s family. During the fighting on the 12th, Oliver was wounded. He would survive and go back into service only to be killed in action near Petersburg, on July 30 during the battle of the Crater.

Discovering these connections I have with Oliver and Charles prompted me to look more closely at the Bixby story. Certainly, their deaths together were tragic enough, and the possible death of POW brother George Way Bixby at Salsbury Prison would make it even worse. George fought in the 56th Massachusetts in Brig. Gen. Thomas G. Stevenson’s IX Corps division and was captured at the Crater on the same day his brother Oliver was killed. Unconfirmed reports also seem to suggest George may have galvanized while in captivity—that is, enlisted with the Confederates in exchange for freedom.

Another brother, Arthur Edward Bixby, 18 years old when he enlisted in June 1861, definitely deserted. He served with the 1st Massachusetts Heavy Artillery but left his post at Fort Richardson, Virginia, eleven and a half months into his service. Perhaps it saved his life. The 1st Mass Heavies saw brutal action when they first went into combat on May 19, 1864, at Harris Farm during the battle of Spotsylvania Court House.

Only Cpl. Henry Cromwell Bixby, 31 years old when he enlisted with the 20th Massachusetts alongside his brother Charles, served long enough for an honorable discharge. Captured at Gettysburg, he was paroled in March 1864 and went home.

The tragedy of five dead Bixby brothers appears to be hogwash. And to add insult to injury, Mrs. Bixby was reportedly a Confederate sympathizer, or so descendants later attested. She apparently found Lincoln’s letter not touching or consoling but offensive.

The story gets even murkier. Debate has raged for 160 years over Lincoln’s authorship of the letter. Some scholars believe Lincoln’s secretary, John Hay, wrote the letter because the writing style more closely resembles Hays’s. Unfortunately, the original copy of the letter was lost, so there’s no way to check handwriting.

As it turns out, Spielberg’s retelling of the story in Marshall’s office might have been the truest part of the entire Bixby myth!

Here’s the scene in case you’ve never seen it:

The Bixby letter has a Lincolnian lyricism that John Hay’s florid letters of condolence don’t. Suggesting that, if the letter did not originate with Lincoln, he as a master editor, rewrote Hay’s attempt, much as he had done with William Seward’s suggested closing paragraph to the First Inaugural Address, thus creating literary gold.

Huge John Hay fan here–but I think you are correct. I think this letter is a distillation of both Hay and Lincoln, just as I think Lincoln’s letter to Elmer Ellsworth’s parents has the fingers of Hay in there as well. What a brilliant combo of writers, however. Sort of like JFK & Ted Sorenson.

Thanks for the thought-provoking report. “The fog of war” is one of the reasons why soldiers “who failed to muster after battle,” without evidence that they were wounded or killed, were labelled as “missing.” It then required further investigation to determine whether that missing soldier had a better defined status: captured; lost/absent (reported to wrong unit); Dead (unknown cause); Dead (due to misadventure or accident) Dead (while POW); wounded (status determined upon receipt of Hospital report); absent (reported a few days later and returned to service); deserted (abandoned the unit with the intention of never returning.) If upon investigation a soldier’s status remained “undetermined,” he remained listed as “missing” …although an assumed status might be included, i.e. “Missing: presumed drowned.”

There were serious implications to labelling a soldier as “Deserter.” Not only was that man’s life in peril, if caught; but his wife or parents stood to lose all claim to War Pension entitlements. Therefore, it appears the classification, deserter, was not applied until there was an element of certainty. [On the day that President Lincoln composed his letter, it would be interesting to know the Official Status of each of the five Bixby men.]

Whatever the full story of the Bixby Family, the Mother suffered enough personal tragedy to warrant a Letter from the President.

One would suspect that the sixteenth President of the United States anticipated that the sending of such a letter to the office of the Governor of Massachusetts would inevitably be published in Bostonian newspapers.and thereby garner to him, Mr. Lincoln, the deepest public accolades and admiration. Certainly such has proven to be the case, much as the verses pronounced in Pennsylvania the year before. Whether the Commander-in-Chief was aware of the error of the actual circumstances or not, this letter was assuredly a vast PR coup for “A. Lincoln.”

Interesting that brother Henry was captured while being in the 20th Mass at Gettysburg. Presumably his capture happened on July 2 or July 3 when the 20th Mass helped to repulse first Wright’s Georgia brigade and then Pickett’s Charge, respectively. In either case, the chances of a Union soldier being captured and held by Confederate forces during these firefights — and later sent to a prison camp were extremely low given that the engagements took place on Cemetery Ridge! Poor guy!

After doing a little more digging on Henry, he was serving in the 32nd Massachusetts Infantry when he was captured in the Wheatfield on July 2, 1863 at Gettysburg. This makes more sense than being captured on Cemetery Ridge with the 20th Massachusetts. Henry had served in the 20th Massachusetts earlier in the war and switched to the 32nd Massachusetts in August 1862.

Harve Presnell does an outstanding job portraying General Marshall. The Ryan brothers were modeled in some degree after the Niland brothers – 3 KIA, 1 believed KIA but discovered as a POW in 1945.

Chris: I completely agree on the Marshall portrayal. WWII was a fitting era for using the Bixby letter. The deaths of the five Sullivan brothers on the USS Juneau in 1942 off Guadalcanal was another such event. And they were, of course, of Irish descent and from Iowa …..

well, “hogwash” and Mrs. Bixby’s “Confederate sympathies” notwithstanding, i am moved by the sacrifice of the Bixby family — three of five sons killed in the war … for all you parents, imagine losing a son or daughter in Iraq or Afghanistan — unthinkable … now imagine losing three … perhaps, some of Mrs. Bixby’s angst over “so great a sacrifice” was shining through.

getting it right is historically important, but in this case i am granting the author — Lincoln or Hay — and Mrs. Bixby family a lot grace … for me, letter remains a beautifully written exemplar of the sympathy of a grateful republic for the service of its soldiers and their families.

In my family history, we had a Bixby-like situation with the Smith brothers of Overton County, Tennessee. Seven of them joined Company H, 3rd Kentucky Infantry (Union). Six would die in the war – two from disease, one from either disease or guerrilla ambush, one at Chickamauga, and two at Rocky Face Ridge. William Clay Smith survived the war. It was thought he was an ambulance driver. Their story was featured in a five-part series in the Overton County News in 2012.

With the size of families up until the latter half of the twentieth century, it is not inconceivable that this circumstance occurred with some frequency, even up to the Second World War.My father had two brothers: the youngest did not enlist; the middle was in a support branch of the U.S. Army. My father was the only one of the three who saw combat, as an artillery liaison officer and battery commander in Europe in 1944-1945.

Out of curiosity, is Sgt. Charles Bixby buried in Fredericksburg?

Here is a link to his Find-A-Grave memorial. Looks like his actual burial site isn’t known for certain.

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/49438012/charles-n-bixby

Here is a link to the Find-A-Grave memorial for Oliver Cromwell Bixby. The entry includes some information on his family.

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/49438379/oliver-cromwell-bixby

Yes, that scene in the movie always gets me. There is nothing more profound to any veteran than to see “the brass” appreciate the sacrifice we make. Up in their ivory tower, we want to believe they appreciate the struggles at the line.

Tom

Its interesting that they chose the Marshall character to make that point. In reality, Marshall was more of a field soldier, who very much wanted to be in the field, not the ivory tower. One could well believe he might make such a decision and have memorized that letter.

Tom

What if the real letter still exists? What would one do if the found a letter like this? This bring much confusion to all but I’m honestly interested in know what to do if something of this was found and what type of value would it be worth?

It might be possible that the original still exist. In the 1970’s, Robert E Lee’s Amnesty Oath had been lost in the National Archives and his citizenship was not restored until 1975, more than 105 years after his death. So you never know about such things, the original Bixby letter may yet still be out there somewhere.

I do find it interesting to find out that Mrs. Bixby may have been a Confederate sympathizer. Me, myself, I am a Confederate Partisan.

I agree. Long lost primary sources have occasionally materialized.

My first impression was that the commanding officer of the Third Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia had insight into this subject, which would be remarkable indeed.