The Rocks at Second Manassas: A Postscript of Reconstruction

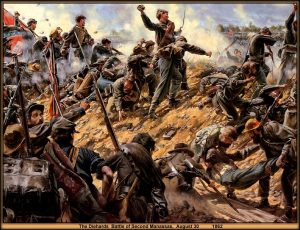

A little while ago, Sarah Bierle shared the story of Confederates, out of ammunition, resorting to throwing rocks at the Deep Cut during the battle of Second Manassas. It’s a fairly well-known account, held up as an example of the nature of the close quarters fighting that took place on Aug. 30, 1862.

Sources credit Private Michael O’Keefe of the 1st Louisiana for being the one to stand up and shout out “Boys, give them the rocks!”[1] Little has been written about O’Keefe outside of his episode at Manassas, but the end of his life provides a fascinating postscript to the Civil War. This post examines what is known about O’Keefe’s wartime service, and ultimately, his murder by white supremacists in 1874.

Born in Ireland circa 1832, O’Keefe immigrated at some unknown point and was living in New Orleans when the Civil War broke out. He stood five and a half feet tall, had dark hair, a fair complexion, and blue eyes. His Compiled Service Record indicates he enlisted in the 1st Louisiana Infantry on April 28, 1861, for a duration of one year. When his enlistment ran out a year later, O’Keefe remained in the Confederate Army, caught up amidst the general conscription that the Confederacy resorted to the spring of 1862. O’Keefe later told Federal authorities that he “has been kept in the Rebel service against his will.”[2]

Now a conscript, O’Keefe served in all the Army of Northern Virginia’s campaigns from the spring of 1862 going forward, including his famed stand at Second Manassas. His Service Record does not indicate any significant time missed; every monthly report from the spring of 1862 onwards marks O’Keefe as “Present.” After the bloodletting of 1862, O’Keefe fought alongside the 1st Louisiana at Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, and the fall campaigns of 1863, receiving a promotion to sergeant.

O’Keefe’s charmed life, surviving every battle unscathed and not even appearing to be sick at any time during the war, came to an end at Spotsylvania. After heavy casualties sustained at the Wilderness, both brigades of Louisianans in the Army of Northern Virginia were consolidated into one, and assigned to defend the tip of the Mule Shoe Salient. During the dawn assault there on May 12, 1864, the Louisianans were quickly overrun and O’Keefe found himself a prisoner of the United States Army. He was forwarded to the prison at Elmira, New York. O’Keefe remained at Elmira for nearly a year before he was released on May 13, 1865. In New York City he took an oath of allegiance and made his return to New Orleans.[3]

By 1870, O’Keefe had married a woman named Maria and taken a job as a patrolman in the ranks of the Metropolitan Police Department. The Metropolitan Police, formed in 1868, was an integrated police force, much to the ire of white supremacists in the city. An interesting tidbit of O’Keefe’s time with the Police Department can be found in what amounts to a throwaway line in a letter written by someone who knew him in New Orleans. W.M. Owen, who had served in New Orleans’s famed Washington Artillery during the war, wrote O’Keefe “was true but said he ‘must make his bread.’” Owen did not elaborate on his statement, so what he meant by “true” remains unclear. It seems most likely that former Confederate comrades looked down on O’Keefe’s service with the police during Reconstruction, a charge O’Keefe defended by claiming he was simply making a livelihood.[4]

By the fall of 1874, O’Keefe was still serving with the Metropolitan Police Department. He soon found himself in a new battle—one being waged by some of his former comrades against Republican rule and opposing Reconstruction in Louisiana.

Violent resistance to Reconstruction began almost as soon as the war ended, and was especially intense in New Orleans. In 1866, former Confederates massacred hundreds of Blacks in the streets near the Mechanics Institute. But it was the 1872 gubernatorial election that proved the backdrop for the final saga of Michael O’Keefe’s life. William P. Kellogg, the Republican nominee, ran against Democrat John McEnery. “Intimidation and fraud marked the contest,” historian James Sefton wrote.[5] In the end, though both sides claimed victory, President Grant recognized Kellogg as the winner. Kellogg was inaugurated in January 1873. Four months later, in April, outside of Colfax, Louisiana, nearly 150 Blacks were massacred.

Resistance to Kellogg’s governorship continued into 1874, and led to the creation of White Leagues, which were “openly dedicated to the violent restoration of white supremacy.”[6] In August, six Republican officials were murdered by White League members in the Red River Parish. By the fall, Governor Kellogg had little political control outside of New Orleans. And the White Leagues sought to change that, too.

In September, detectives within the Metropolitan Police received word that the White Leagues were having guns and ammunition shipped to New Orleans. On September 13, bulletins posted throughout the city called for businesses to close and for White League “companies” to march against Republican rule. “Hang Kellogg!” insurrectionists called out.[7] Former Confederate general James Longstreet, now a general of Louisiana militia, gathered troops and police officers to oppose the White Leagues.

The powder keg exploded on September 14, 1874. White Leagues across the city mobilized and began moving against the police and militia. Longstreet, trying to intercede, was shot in the leg and unhorsed. A wild melee broke out, with gunfire in all directions. The skirmish did not last long, perhaps as little as fifteen minutes. By the time the gun smoke cleared, some twenty White Leaguers were dead, with another twenty or so wounded. The Metropolitan Police Department had at least eleven officers killed, and, some accounts suggest, at least sixty wounded. Laying among the dead was Officer Michael O’Keefe. A coroner’s inquest convened in the wake of the insurrection reported that four police officers, including O’Keefe, had been wounded in the brawling around a building defended by the Police. Someone, or perhaps multiple people, though it was unknown who, had murdered the injured officers as they lay in the street by putting pistols up to their foreheads and pulling the triggers.[8] It’s unclear what happened with O’Keefe’s remains, or where he was buried.

The fighting on September 14, which historian Eric Foner refers to as “armed rebellion,” came to be known as the Battle of Liberty Place. Getting word of the violence, President Grant ordered Federal troops into the city. Their arrival quickly dispersed the White Leagues, and Kellogg remained governor until 1877.[9]

In the end, Michael O’Keefe, who resorted to waging war with rocks at Manassas, gave his life in service against anti-Reconstruction forces. History is full of coincidences big and small, and it is among those coincidences that we find the possibility that someone who threw rocks alongside O’Keefe at Manassas in 1862 ended up murdering him twelve years later. O’Keefe’s story also reminds us that while the war may have ended in 1865, it continued by proxy for years afterwards in the bloodshed of Reconstruction.

___________________________________________________________

[1] John Hennessy, Return to Bull Run: The Campaign and Battle of Second Manassas (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1993), 357.

[2] Michael O’Keefe Compiled Service Record, Page 23.

[3] Ibid.

[4] W.M. Owen to Allen C. Redwood, February 28, 1886, in the Allen C. Redwood Collection, formerly in the Eleanor Brockenbrough Library, Museum of the Confederacy. As the Museum of the Confederacy became the American Civil War Museum, many of its archival sources were sent to the Virginia Museum of History & Culture.

[5] James Sefton, The United States Army and Reconstruction, 1865-1877 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1967), 239.

[6] Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877 (New York: HarperCollins, 1988), 550.

[7] Stephen Budiansky, The Bloody Shirt: Terror after the Civil War (New York: Penguin Group, 2008), 159.

[8] Justin Nystrom, “Redeemer’s Carnival: The Urban Drama of Reconstruction in New Orleans,” (University of Georgia PhD Dissertation, 2004), 174.

[9] Foner, 551; Charles W. Calhoun, The Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2017), 460.

Thanks for sharing O’Keefe’s story. It is always cool when you can trace an individual common soldier through the war and beyond to create a coherent timeline and story and O’Keefe’s story highlights some of the many wartime issues and postwar complexities.

Interesting examination of the postbellum life of a Confederate soldier of some note. Political choices during reconstruction were often motivated by multiple factors and issues. For example, a notorious Confederate cavalry leader, whom W.T. Sherman would lump into a group with N.B. Forrest, became the Republican postmaster of Jackson, Mississippi, and was shot and killed by the editor of a Democratic newspaper on the streets of that city.

Thank you for sharing O’Keefe’s life with us. Life is something else.

Thank you for publishing yet another story of the difficulties that persisted long after the Civil War “concluded.”