Enforcing Emancipation: General Robert Milroy and Winchester, Virginia

“New Year’s Eve. A sad and dismal time, weather dark and gloomy, and everyone more depressed than I have ever seen them. We are told that tomorrow emancipation is to be proclaimed from the Courthouse, with the ringing of bells, and that the soldiers are to be quartered on the citizens without distinction….”[i]

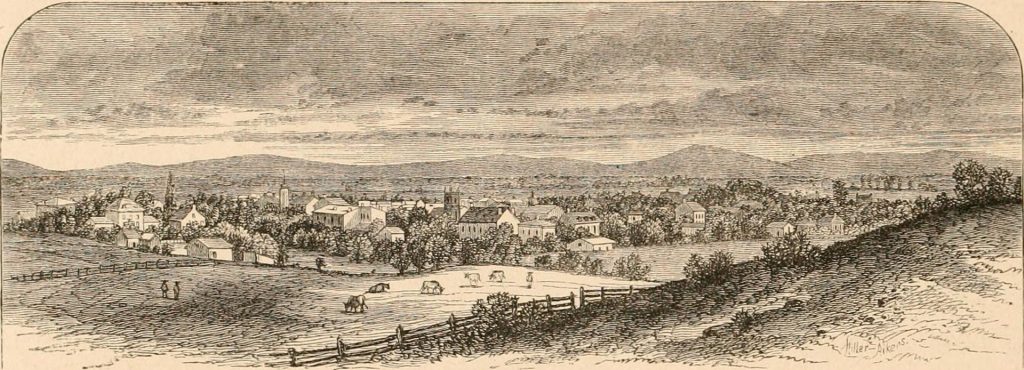

Laura Lee’s diary entry from December 31, 1862, reflected the mood of many white, Confederate-supporting women in Winchester, Virginia on the eve of 1863. The period traditionally known as the Twelve Days of Christmas (December 25-January 6) marked a turning point in both national and local events, producing a variety of reactions in the Winchester community. Most significantly, the arrival of Union General Robert Milroy and more soldiers on January 1, 1863, coincided with the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, a document that Milroy anticipated enforcing in the Virginia city that he occupied. For enslaved people in Winchester and the surrounding counties, the promise of freedom would be protected and enforced under Milroy’s precedents. For white people in military uniform or civilian status, the enforcement of the Emancipation Proclamation produced varied reactions, from open hostility to veiled mutterings to enthusiastic contributions.

The arrival of soldiers in blue around Christmas Eve 1862 annoyed many of Winchester’s white civilians and incidents in the last days of December increased their grievances. In the gloomy winter days, their homes were systematically searched for weapons, alcohol, and bacon, fences were torn down for fire fuel, and an organized “chicken stealing expedition” occurred.[ii]

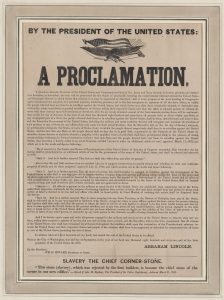

White civilians knew about Lincoln’s promise to sign the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. In September, the president had stated that “on the first day of January…all persons held as slaves within any State, or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”[iii] Unionist Julia Chase noted in her diary on January 1: “According to the President’s Proclamation, all the slaves are to be freed from today. This will give great dissatisfaction to slaveholders but joy to the Negroes. I doubt whether they will be better off by their freedom.”[iv]

In the days leading up to 1863 and for nearly the first week of January, the enslaved Black population in and around Winchester waited. One Union soldier thought it was “strange to say the colored people of Winchester seemed utterly ignorant of the fact that there was such a thing as any proclamation of freedom.”[v] It is more likely that many enslaved individuals did know about the promised Emancipation Proclamation for January 1, but they likely waited to see if the Federal troops would be staying in Winchester for a lengthy period. In previous months, Union soldiers usually stayed in Winchester only a short time before retreating further north. To make their own acknowledgements of hopes for freedom without knowing if they would be protected in that freedom could have been dangerous. Already, enslaved men had been sent from the city and local counties to meet “quotas” of slave labor required by the Confederacy for the defenses of Richmond and other military projects created or maintained by forced work.[vi] The risks stood high to openly talk about freedom, likely leading many enslaved people to hope in secret and wait to see if the new arrival of Federal troops offered any definitive news or protection.

Another diarist, Mary Greenhow Lee, noted cheerily on January 1 that “the day has passed with less excitement than we anticipated – there was no further announcement of emancipation & we find from the papers that Lincoln is afraid to carry out his plan, as yet. Milroy arrived to-day with the rest of his command….”[vii] Four days later, Laura Lee (Mary’s niece) wrote, “Yesterday Lincoln’s proclamation came in the papers, but thus far we have seen no effects of it…..”[viii]

However, forty-six year old Robert Milroy had already made enthusiastic announcements to his soldiers. On the road to Winchester on New Year’s Day, Milroy had ridden along his marching column in great excitement, saying, “this is Emancipation Day, when all slaves will be made free.”[ix] Before he allowed the soldiers to encamp at Winchester, he told the regiments that this day marked “the most important event in the history of the world since Christ was born. Our boast that this is a land of liberty has been a flaunting lie. Henceforth it will be a veritable reality.”[x]

A staunch abolitionist, Milroy’s strong Presbyterian faith influenced his belief that God appointed people to certain times, places, and events. He wrote to his wife, “I am enforcing the proclamation of the President of the U.S., freeing the very slaves that old John [Brown] so insanely attempted to free…Plainly these events are directed and controlled by the Infinite Being who holds the nations of Earth in the hollow of his Hand.”[xi] Conscious of the history of Winchester and the lower Shenandoah Valley, Milroy had entered the region of John Brown’s 1859 uprising hopes, the hometown of the author of the Fugitive Slave Law (1850), and the hometown of the judge who sentenced John Brown to hang. Time, place, individual, and event intersected on January 1 as Milroy rode into Winchester. He knew it, and he would find a way to proclaim and guarantee freedom to the enslaved in his military jurisdiction.

Still, Milroy waited. Other abolitionist generals had acted too hastily in 1861 and 1862, leading to figurative hand-slaps from Lincoln or his administration. Milroy had to make sure that the president had really signed the Emancipation Proclamation. The wait for news to travel buoyed the hopes of the slaveholders and other white civilians that either the proclamation had not been signed or the new occupier would not care about it.

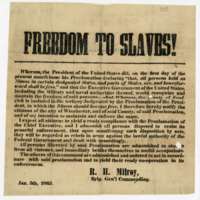

On January 4, the news arrived. White civilians, General Milroy, and Union soldiers read the news: Lincoln had signed the Emancipation Proclamation. Slaves in states or parts of states still in rebellion would be free. Milroy studied the precise wording of the historic document, probably focusing on the areas specifically named; some Virginia and West Virginia counties were specifically exempted from the proclamation, but Frederick County and Winchester were not on that list. Yes, Winchester met the criterion as an area still in rebellion. He could officially proclaim, offer, and enforce liberation. Once he had clarified the details, Milroy wasted no time and did not give his officers a chance to debate the situation. On January 5, Union soldiers pasted and hammered printed proclamations around Winchester, then started taking the news to other nearby towns.

After the emblazon news, Milroy’s proclamation stated that he expected a few particular things:

Freedom to Slaves!

Whereas, the President of the United States, did, on the first day of the present month, issue his Proclamation declaring “that all persons held as Slaves in certain designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free,” and that the Executive Government of the United States, including the Military and Naval authorities, thereof, would recognize and maintain the freedom of said person. And Whereas, the county of Frederick is included in the territory designated by the Proclamation of the President, in which the Slaves should become free, I therefore hereby notify the citizens of the city of Winchester, and of said County, of said Proclamation, and of my intention to maintain and enforce the same.

I expect all citizens to yield a ready compliance with the Proclamation of the Chief Executive, and I admonish all persons disposed to resist its peaceful enforcement, that upon manifesting such disposition by acts, they will be regarded as rebels in arms against the lawful authority of the Federal Government and dealt with accordingly.

All persons liberated by said Proclamation are admonished to abstain from all violence, and immediately betake themselves to useful occupations.

The officers of this command are admonished and ordered to act in accordance with said proclamation and to yield their ready cooperation in its enforcement.

R.H. Milroy, Brig. Gen’l Commanding

Jan. 5, 1863[xii]

By January 7, 1863, Laura Lee wrote: “Milroy has had the freedom proclamation posted up all over town, and the men and even the officers are going about among the servants reading it to them, and assuring them that they are perfectly free. Thus far ours have given no sign of any change, but I suppose they are all waiting for some bold spirit to take the initiative….”[xiii]

Perhaps the continued hesitations that Laura Lee observed can be better understood in the context of the rumors circulating through Winchester and probably overheard by the enslaved individuals. Most of the white female diarists devoted more paper and ink to the rumors that “Stonewall” Jackson was moving toward Winchester (he was not), a Confederate victory in Tennessee (Stone’s River was a Union victory), and various stories about Confederate military movements in the Shenandoah Valley (there was not anything significant in the winter months). It took time for freedom’s hopes to become realities. It took time for courage to grow.

Reactions among the soldiers under Milroy’s command to the proclamation varied. Some stood on the streets and read the news and the placards to African Americans. Some seemed to not care one way or another. Others were openly hostile and wrote that they would not fight for freedom, usually adding name calling or language that is considered racist and offensive in the 21st Century.[xiv] General Cluseret actually resigned, partly out of his disgust at Milroy’s efforts to enforce and protect emancipation.[xv]

By the end of January, Milroy’s efforts had produced confidence, and African Americans left slavery and started making their way toward new lives of their choosing. Unionist Julia Chase noted on January 28: “The blacks are leaving in great numbers, and probably in the course of a few weeks there will be but very few left. We shall be at a great loss to get anything done….”[xvi] The exodus from slavery continued through the spring, and Milroy was not passive in his efforts. Laura Lee complained on March 2: “The soldiers are scouting through Clarke Co., and bringing in large numbers of Negroes who had been satisfied to stay at their houses. There are hundreds waiting here to be sent on to [Pennsylvania]. Ours still are vehement in their loyalty, but there is no faith to be placed in one of them….”[xvii]

To white Virginians in the lower Shenandoah Valley, General Milroy represented one of the greatest threats to their “way of life.” He systematically dismantled “the peculiar institution” and defined loyalty and treason in stark terms with clear actions and consequences. His interactions with white civilians became the stuff of bitter legends, sketches, and long-remembered animosity. However, Milroy had found purpose and stayed his course. Proclaiming freedom and creating a military situation where he could facilitate and protect enslaved people stepping forward into liberty gave him purpose. From January 1 until June 15, Milroy and U.S. soldiers occupied Winchester and during that time hundreds of African Americans started new chapters of lives.

Not all Union generals and soldiers supported the Emancipation Proclamation. Many—perhaps even a majority—opposed it in 1863 with varying degrees of hostility. What happened in Winchester, Virginia during Milroy’s occupation is somewhat unique. His swift response, active proclamation, and strong protection for freedom-seekers ensured that the statement “henceforward and forever free” became a true reality in that city and region.

Sources:

[i] Julia Chase and Laura Lee, edited by Michael G. Mahon, Winchester Divided: The Civil War Diaries of Julia Chase and Laura Lee (Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books, 2002). Page 75.

[ii] Ibid., Pages 74-75.

[iii]Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation: https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/american_originals_iv/sections/preliminary_emancipation_proclamation.html

[iv] Julia Chase and Laura Lee, edited by Michael G. Mahon, Winchester Divided: The Civil War Diaries of Julia Chase and Laura Lee (Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books, 2002). Page 75.

[v] Jonathan A. Noyalas, Slavery and Freedom in the Shenandoah Valley during the Civil War Era (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2021). Page 89.

[vi] Ibid., Page 93.

[vii] Mary Greenhow Lee, edited by Eloise C. Strader, The Civil War Journal of Mary Greenhow Lee (Winchester: The Winchester-Frederick County Historical Society, 2011). Page 176.

[viii] Julia Chase and Laura Lee, edited by Michael G. Mahon, Winchester Divided: The Civil War Diaries of Julia Chase and Laura Lee (Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books, 2002). Page 76.

[ix] Jonathan A. Noyalas, Slavery and Freedom in the Shenandoah Valley during the Civil War Era (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2021). Page 88.

[x] Ibid., Page 88.

[xi] Ibid., Page 89.

[xii] Robert Huston Milroy, “Freedom to Slaves!,” Remaking Virginia: Transformation Through Emancipation, accessed January 6, 2023, https://www.virginiamemory.com/online-exhibitions/items/show/431.

[xiii] Julia Chase and Laura Lee, edited by Michael G. Mahon, Winchester Divided: The Civil War Diaries of Julia Chase and Laura Lee (Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books, 2002). Page 76-77.

[xiv] Jonathan A. Noyalas, Slavery and Freedom in the Shenandoah Valley during the Civil War Era (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2021). Page 91.

[xv] Cornelia P. McDonald, A Woman’s Civil War: A Diary, with Reminiscences of the War, from March 1862 (New York: Gramercy Books, 1992). Page 114.

[xvi] Julia Chase and Laura Lee, edited by Michael G. Mahon, Winchester Divided: The Civil War Diaries of Julia Chase and Laura Lee (Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books, 2002). Page 79.

[xvii] Ibid., Page 81.

I really enjoyed this post! I’ve been fascinated by Milroy since reading the Confederate government put a bounty on his head.

As always, Sarah has written a very well researched and insightful article. She mentioned in her piece “slave quotas”, not being familiar with this demand of the Richmond government, I would like to find out more about it.

Yea, Milroy was quite a character. He exiled Winchester families for violating his rules. He exiled folks who provided goods or information to Confederate forces. But, he also exiled folks who simply voiced support for the Confederate forces in which their sons, fathers and neighbors served. He exiled folks who wore a ribbon for the deceased Stonewall Jackson in May, 1863. He said “his will was absolute law.” and he meant it.

He exiled the Logan family at the corner of Braddock and Picaddilly streets because they harassed a “Jessie Scout” – Union soldier dressed as a Confederate. But, the Winchester residents say he exiled the Logans mainly because his wife wanted their house. He saw himself as fulfilling the role of an Old Testament prophet ending slavery. Thank goodness he did. But, he could have employed New Testament charity in the process.

Tom

Indeed, prior to Winchester duties, Milroy held responsibility for dealing with Southern partisans in West Virginia. Unable to catch them, he took focused on the “known” Confederate sympathizers. He decided that Union supporters who suffered from the partisan raids would present a bill for the value of property lost. Local commanders would then apply that bill to “known” Confederate supporters in their area. If the Confederate supporter failed to pay, the sympathizer’s house would be burned and the Confederate supporter would be shot. Thus, one West Virginian had to pay $1,000. Another 82 year old German immigrant – infirm – had to pay $285. This order produced some $6,000. Protest was sent from Gen. Lee to Gen. Halleck. Halleck found the order to violate the rules of war and that Milroy lacked the authority for such measures. Thus began long antagonism between Milroy and Halleck.

Regarding Brig.-Gen. Cluseret, yes, Cluseret objected to “fighting for Negroes,” but he also objected to arresting women. And he believed that it violated the rules of war to refuse to feed prisoners – in which he was correct. And, he believed that maintaining some accommodation with the locals would assist in the Federal occupation. Milroy reversed Cluseret’s more accommodating policies.

Tom

I enjoy many of SKB’s posts, including this one. General Milroy presents as a true “character.” I look forward to reading the Wittenberg-Mingus book on Second Winchester, which, I suspect, will reveal Milroy in an interesting light.

Great article Sarah! Milroy is a fascinating character. For a deeper dive on Milroy, try this:

Noyalas, Jonathan A. (2006). “My Will Is Absolute Law”: A Biography of Union General Robert H. Milroy. McFarland.