The “Other” Lee

Mention the surname “Lee” to a Civil War enthusiast or quite possibly any American that sat through a high-school American History class and the name Robert E. Lee is the first one given in reply. Ask that Civil War enthusiast to mention another “Lee” that fought in the Civil War and that person would respond with either Fitzhugh Lee or Rooney Lee, both correct answers.

Yet, there was another “Lee” with no relation to the Lees’ of Virginia who served admirably and faithfully to the Confederate cause too. He even served longer than the three gentlemen officers that shared his same last name. Unlike those Lees he was not a Virginian, but claimed Charleston, South Carolina as his birthplace and hometown.

Stephen Dill Lee was born in that port city of the Palmetto State on October 22, 1833 and at the age of 17 entered West Point Military Academy where he graduated 17th in his class. The next four years Lee would serve around the United States, from the newly formed Dakota Territory to the tropical clime of Florida. During that tumultuous winter of 1860-1861, Lee resigned his commission in the United States Army on February 20, 1861 and began service in the South Carolina Militia as a captain and Assistant Adjutant and Inspector General of the Forces at Charleston. In April Lee was commissioned a captain Confederate service and was chosen for a plum assignment as an aide-de-camp to General Pierre Gustave Toutant “P.G.T.” Beauregard.

Lee would become quickly played a part in the escalating tensions around Charleston Harbor on the morning of April 11th. Lee was tasked with rowing a communiqué out to Major Robert Anderson of the United States Army who was commanding Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. Beauregard entreated Anderson to surrender his post, but the Union major declined and the first shots fired in anger in the American Civil War followed.

During the build-up that followed, Lee returned to his position in the South Carolina Militia after briefly commanding an artillery battalion at Castle Pinckney and Fort Palmetto, both near Charleston. His invaluable service to Beauregard plus his pre-war army experience would single out Lee for further promotion and a chance to play a more active role in the expanding conflict.

Being, according to Ezra Warner, “an artillerist” by profession Lee was promoted in June 1861 to major in the Confederate Army and marched toward Virginia in command of a light battery in General Wade Hampton’s Legion. He began a stellar career in charge of artillery that would lead to another promotion in March 1862 to lieutenant colonel and the following month to assignment as chief of artillery in Major General Lafayette McLaw’s Division.

After stellar service during the Peninsula Campaign and brief service in the cavalry, Lee was appointed commander of an artillery battalion in Major General James Longstreet’s wing in July. He would later take control of all artillery under Longstreet.

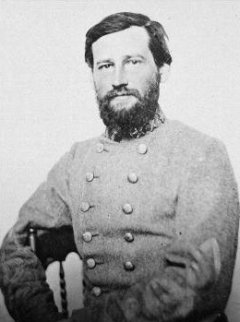

All this was a warm-up to the impeccable service Lee would serve at Antietam. Described as a “slender [and] dark-bearded” historian Richard Slotkin writes that it was on that September day Lee showed the “abilities [that] would eventually earn him command of an army.”

At the Battle of Antietam, Lee’s artillery would play a major part in the defense and actually play a role in defending all three sections of the Confederate battle line. By 9 a.m. Lee’s batteries had already suffered enormous casualties but following the assaults along the Sunken Road and middle of the Confederate defensive line Lee’s artillerists actually found themselves the only Confederate defending a few hundred yard line. They continued at a rapid rate firing shells into the Union ranks until the blue-clad soldiers halted their advance and infantry was rounded up to plug the gap. The now famous photo of Confederate dead in front of Dunker Church is of members of batteries commanded by Stephen Lee.

One Union infantrymen attested to the accuracy and rapidity of shots fired by Lee’s artillerists; “The shot and shell fell about us thick and fast, I can tell you.”

By the end of the day, Lee reported to Robert E. Lee about the severe losses suffered by his batteries. According to his official report, the artillery commanded by Lee suffered 86 casualties out of a force of approximately 300 in addition to the loss of 60 horses.

Yet, Lee’s guns stood, like the rest of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia in the same general defensive area on the morning of September 18th as they did the previous day. Early that morning of the 18th, General Lee thought an opportunity could be presented along General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s front.

Showing the rising trust the upper echelon of Confederate command had with artilleryman Lee, he was sent to provide his input and he surveyed the lines with Jackson. The eccentric wing commander informed Lee; “I wish you to take fifty pieces of artillery and crush that force which is the Federal right. Can you do it?”

Lee responded, “Yes, General, where will I get the fifty guns?”

“How many do you have?” asked Jackson. To which Lee answered, “About twelve out of the thirty I carried into action yesterday, my losses in men, horses and carriages have been great.”

After a few more minutes of dialogue, Jackson asked for Lee to give his “positive opinion, yes or no” on whether the artillery could play its part in the proposed assault. Lee after surveying the field remarked, “General, it cannot be done with 50 guns and the troops you have near here.” With that Jackson—of the same mind apparently—directed Lee to ride back with him to inform the army commander.

Lee thought he had failed and quickly asked permission to “fight the guns to the last extremity.” Jackson according to Historian James V. Murfin, was “benevolent in attitude and perhaps with a slight grin” answered the young South Carolinian.

“It is all right, Colonel, everybody knows that you are a brave officer and would fight the guns well.”

The following day, Lee and the rest of the Army of Northern Virginia retreated back to Virginia. The campaign had ended with a downward turn, but Lee’s stock was quickly going the other way.

On November 6th Lee received his brigadier general’s star and with it a promotion to command General Pemberton’s artillery at Vicksburg.

Out west he was transferred to command infantry and led a division at the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou in December 1862. He commanded a force half the size of the Union assault force but used the excellent terrain for his defense in repulsing with heavy loss the blue-clad assaults. The following May, he again led infantry at the Battle of Champion’s Hill, where he received a wound in the shoulder. Although not serious the wound rendered the arm “very painful and later turned black from the shoulder to the elbow.” One account pegged Lee as “the hero of Champion Hill.”

(courtesy of Vicksburg NMP)

Like the rest of the Confederate garrison though, he was surrendered on July 4, 1863. By the end, according to Lee, Vicksburg was “full of sick and wounded men, quarter-master, commissary employees and extra duty men, and hangers on of every kind.” These men were given paroles although they took no part in the fighting, something that Stephen Lee biographer Herman Hattaway hinted had discouraged the South Carolinian.

While on parole Lee was promoted on August 3rd to the rank of major general. With the promotion came another switch in branch of service, as he was tabbed to command the cavalry in the Department of Mississippi, Alabama, West Tennessee, and East Louisiana on August 16th. Yet he would not be official exchanged until October. By May 1864 Lee was in charge of the Department of Alabama and East Louisiana.

During his tenure as commander of this district he was the superior officer of the famed cavalier Nathan Bedford Forrest. On June 10th, Forrest scored a victory at Brice’s Crossroads and when reinforced by 2,000 soldiers under the personal command of Lee, fought the Battle of Tupelo. This second engagement which was staged to do further damage to the supply lines of Union General William T. Sherman’s army was defeated by General Andrew Smith blue-clad forces.

Before the Battle of Tupelo, Lee was appointed the rank of lieutenant general on June 23rd. He found out after the Battle of Tupelo that with the rank came another assignment. He was tasked to command General John Bell Hood’s old corps in the Army of Tennessee. Now the youngest lieutenant general in Confederate service, he would lead the corps through the Battles of Atlanta and into the Nashville Campaign that fall.

During the Battle of Ezra Church, it was Lee’s Corps that pitched into the Federals first and the ferocity of the attack left even veteran soldiers startled. One private seeing stretcher bearers rapidly taking the wounded back commented, “Their litters..were as bloody as if hogs had been stuck on them.”

(courtesy of Harper’s Weekly)

Lee’s Corps was the first to begin the invasion of Tennesee crossing the same name river on November 20th. His corps fought in the Battles of Nashville and Franklin, where his command arrived late in the day and undertook a night attack. As Hood’s remnants of an army streamed southward Lee’s Corps comprised the rearguard and at Spring Hill on December 17th, a shell fragment struck his spur and “shattered a few bones in his heel.”

However, he played one more role in the retreat. According to Historian Winston Groom the event took place at a Duck River crossing. As Hood’s army began its retreat from the environs of Nashville, Hood had sent a message to General Forrest, who was Murfreesboro, Tennessee to return to the army. Forrest’s cavaliers arrived at the Duck River the same time General Frank Cheatham’s Southern infantry, preparing to cross. Forrest insisted that the cavalry had the right-of-way to cross. Cheatham countered that the infantry had the priority, replying, “I think not, Sir. You are mistaken. I intend to cross first and will thank you to move out of the way of my troops.”

Forrest, never one to back down from a confrontation, drew his pistol and answered, “If you are a better man than I am, General Cheatham, your troops can cross ahead of mine.” With that the standoff grew and two of the best cursers in the Confederate army began trading barbs. Tensions quickly mounted and as some of Cheatham’s infantry cocked their rifles to protect their commander, Lee’s ambulance came bouncing up the road.

When he heard the commotion, Lee summoned the strength to emerge from the ambulance and intervene in the dispute. He was able to separate the “red-faced generals” and able to effect a solution to the problem.Lee then returned to his ambulance and would make it to Florence, Alabama where he was hospitalized a few days.

As the calendar turned to 1865 Lee was on leave, recovering from the wound yet he did find time to marry Regina Harrison, even though he attended the wedding on February 9th on crutches.

His services though were needed and even asked for. Lieutenant General Richard Taylor thought that Lee’s services were needed with his old corps; wounds permitting. Lee did take over command of his old corps—or what was left of it—on March 18, 1865 around Augusta, Georgia. He would be part of the retreat through the Carolinas. Left without a command as the army under General Joseph Johnston disintegrated he was present for the surrender of Confederate forces at the Bennett Place, outside Raleigh, North Carolina. He was paroled on May 1, 1865.

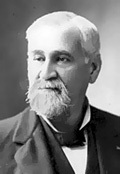

Lee did not return to South Carolina but settled in the home state of his wife, Mississippi. At first he devoted himself to being a planter, but entered politics in 1878 as a state senator and even later served as president of Mississippi State College (now Mississippi State University).

He was also active in the preservation efforts of Vicksburg Battlefield as head of the Vicksburg National Park Association in 1899 and an active member of the United Confederate Veterans. With the turn of the century, Lee’s health worsened and a trip to Hot Springs, Arkansas temporarily decreased soreness in his arm, chest, and back. He suffered from rheumatism beginning in 1900 and had pneumonia in 1905 while having eyesight problems due to cataracts.

His last public appearance was a speech at Vicksburg on May 22, 1908. He complained that night of indigestion—which he attributed to his “heavy supper” at the Carroll Hotel following the day’s events. He moved on to stay at the home of W.T. Rigby and seemed to be in good spirits and improving health, but on the night of May 25th he suffered a stroke. He was unconscious for the last half-day of his life and passed away on May 28, 1908. He was a few month shy of his 75th birthday when he was laid to rest in Columbus, Mississippi.

Ezra Warner labeled him “one of the most capable corps commanders” in Confederate service. His service for the cause was unique as he served in all three branches; artillery, cavalry, and infantry. He was also the youngest lieutenant general in Confederate history.

Even in later life, he was still a die-hard rebel, as his speech to the Sons of Confederate Veterans attests. “To you Sons of Confederate Veterans, we submit the vindication of the Cause for which we fought; to your strength will be given the defense of the Confederate soldier’s good name.”

Overshadowed because of his last name, Stephen Dill Lee had one of the most eventful, distinguished, and interesting services in the Confederate military. As he finished the abovementioned speech to the Sons of Confederate Veterans he wanted one reward for his service to the Confederacy by the members of that organization.

He viewed it as their “duty to see the true history of the South is presented to future generations.”

A Confederate to the last.

(courtesy of Sons of Confederate Veterans)

Sources Used & Further Reading

Stephen Dill Lee:

Herman Hattaway “General Stephen Dill Lee ”

Ezra Warner “Generals in Gray”

Jack Welsh “Medical Histories of Confederate Generals”

Battle of Antietam:

Richard Slotkin “Long Road to Antietam”

Stephen Sears “Landscape Turned Red”

James Murfin “The Gleam of Bayonets”

Western Theatre:

Noah Trudeau “Southern Storm”

Winston Groom “Shrouds of Glory”

Website:

Civil War Trust

http://www.civilwar.org/education/history/biographies/stephen-d-lee-1.html

Reblogged this on Poore Boys In Gray and commented:

This guest blog about Stephen D. Lee doesn’t mention the part he played in the southeast Mississippi homeland of the Poore family.

The family had moved from Newton County a few miles south of the county line into Jasper County in late 1863.

On February 3, 1864, Major General William T. Sherman led 23,519 federal troops out of Vicksburg. The bluecoats struck eastward across the width of Mississippi toward the Piney Woods homeland of the Poore family. The federals headed for the railroad town of Meridian, a major shipping point.

Rebel cavalry Major General Stephen D. Lee had the job of slowing down Union General William T. Sherman’s column long enough to let the Confederate infantry set up a defense line. Lee gathered his horsemen north of Garlandsville, near the Poore family’s Jasper County homestead.

The Yankee invaders entered Newton County on February 12 and Lee’s cavalry made hit-and-run attacks on the 1,000 wagons in the supply train. As it turned out, Lee’s efforts came to nothing. The rebels never made a stand.

Rebel Lieutenant General Leonidas Polk wrongly guessed that the Yanks planned to attack Mobile. Instead of pulling his men together for a defense, Polk scattered the 21,963 troops in the Army of Mississippi across the region, mostly in Alabama.

Lee’s charge to the SCV is still recited at local camp meetings and is on the back of the membership cards.

You are wrong he was related to the lees of Virginia