500 yards

Part one in series

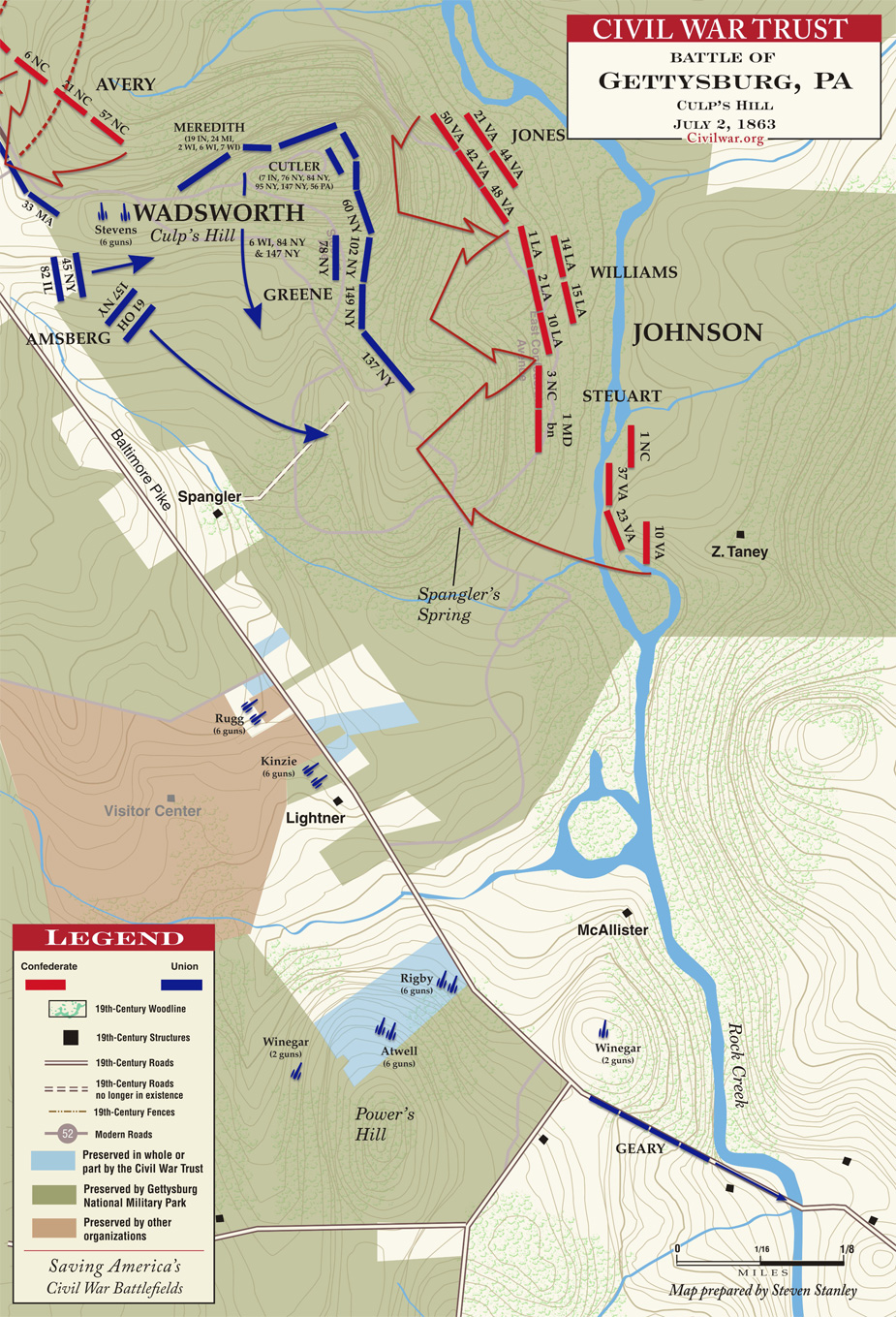

The attack started late in the afternoon of July 2nd. Approximately 2,100 men from three Virginia regiments, two from North Carolina, and a battalion of Marylanders charged up the hill. Overlapping the enemy flank, the charge hit home as daylight waned from the sky. Surging ahead into the darkness, the Confederates got within 500 yards of the Baltimore Pike—one of the main arteries supplying the Union troops in the fishhook portion of Cemetery and Culp’s Hills.

500 yards from coming out on this thoroughfare and behind parts of two Union corps—the I and XI. This would have been the most successful charge at Gettysburg if it would have taken place earlier in the day. Or as Georgian Ambrose Wright would attest to on the other side at Cemetery Hill, if reinforcements would have followed. What made this attack unique was this charge actually ended with Confederate troops holding the captured Federal earthworks and a toehold on Culp’s Hill.

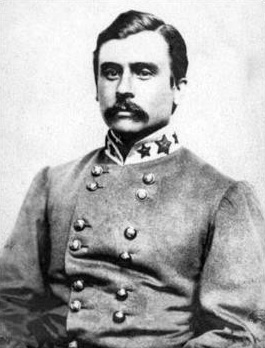

This brigade who exploits were aforementioned belonged to Brigadier General George H. “Maryland” Steuart. Part of Major General Edward Johnson’s Division of Lieutenant General Richard Ewell’s Second Corps, the unit had not arrived at Gettysburg until late on July 1st. Shunted off to the left flank, Steuart’s brigade was one of the last brigades in line in the entire Confederate army (that distinction belonged to the “Stonewall” Brigade), the men went to sleep that night with Culp’s Hill within sight and the sound of the enemy entrenching ringing in their ears.

Yet, the next day the men of Steuart’s Brigade rested and waited—which is trying to any soldiers’ nerves in time of battle. Late in the afternoon an artillery barrage started and shortly thereafter staff officers could be seen riding frantically down the line, a sure indication that an advance was imminent to the experienced soldiers under Steuart, who were still waiting in line. The time was 4:00 p.m.

The men of the brigade sprung to their feet, knowing that this buzzing of activity precipitated the order to advance. Veterans just knew. Lieutenant Colonel James Herbert, in command of the 1st Maryland Battalion, shouted “Forward and Guide center.” With that, like the rest of the brigade, the charge up the heights started.

In front of the advancing Confederates stood Rock Creek and the different commands when facing the terrain features, arrived at the small waterway at different intervals. The men screaming the now infamous “Rebel Yell” splashed across and started the ascent of Culp’s Hill.

(courtesy of LOC)

Coming in on the left flank a few of the regiments—1st Maryland Battalion and 3rd North Carolina, had a little easier slope to cover and pulled ahead of the other regiments. All that stood in front of them was enemy skirmishers of the 78th New York which were easily scattered. Past these skirmishers the Confederates faced a converging cross fire from the Union defenders, due to an angle in the Union fortifications and were caught in the open. As the men hit the ground in front of the Union breastworks casualties mounted, including Herbert of the 1st Maryland. Orders though via Johnson instructed Steuart to bring the rest of the brigade up and the 23rd Virginia came slashing down on the right flank of the five New York regiments holding the hill. These men were under the command of Brigadier General George Greene, who, happened to be the oldest brigade commander in the Army of the Potomac.

The last two Virginia regiments—10th and 37th—came up in support of their fellow Virginians to exploit the Confederate grasp on the Union defenses. At this juncture Steuart ordered his last remaining regiment—the 1st North Carolina forward to support the beleaguered right wing and force the Union defenders from their entrenchments. Only six of the ten companies of the 3rd North Carolina made their way forward. Groping their way forward they made their way to the left flank of the 1st Maryland, this move took the Tar Heels too far out of line to be effective in renewing the assault from Steuart’s right flank.

Darkness enveloped the area but the fighting continued to rage. What was inevitable though was friendly fire incidents which killed an undetermined number of soldiers. In the darkness, Lieutenant Randolph McKim, a staff officer for Steuart, assumed command of this portion of the 3rd North Carolina to fire at the muzzle flashes as they approached the front line. The young lieutenant assumed this fire was from the enemy, but it was not. McKim’s six companies’ volleyed into the Marylanders to their front. Yet, Steuart’s men owned a portion of the Union entrenchments and were able to direct a devastating fire on the exposed wing of Greene’s Brigade. At this point Steuart relied on his experienced regimental commanders which led to further advances, including the capturing of breastworks in front of his right wing by elements of the 1st and 3rd North Carolina and the 1st Maryland Battalion. As Major W.W. Goldsborough of the 1st Maryland recounted, “to stand there was certain death…therefore, why not sell our lives as dearly as possible?” That sentiment prevailed among the Confederates under Steuart’s command during the ensuing hours of carnage and death on Culp’s Hill.

(author’s collection)

The last attack issued by Steuart that day fell on the 10th Virginia who advanced and delivered a telling fire into that exposed flank of the 137th New York, on the extreme right of Greene’s Brigade, finally forcing this stalwart unit from their works. The Virginians hailing from the heart of the Shenandoah Valley, continued their advance into the night. As they did though, Union reinforcements from McKnight’s Hill and the Union center, including a regiment from the Iron Brigade, appeared in their rear and after a welcoming volley from the returning bluecoats forced the Southerners back.

July 2nd thus ended for Steuart’s hard-fighting Confederates. All day the Confederates from one flank to the other had advanced against entrenched Union defenders. Yet, by the time the calendar flipped from July 2nd to July 3rd, only one Southern brigade still held onto a portion of the Union lines. And this brigade was, as Historian Bradley Gottfried stated, “an anomaly” being comprised of regiments from three different states; including one that had not seceded and joined the Confederacy!

Notice the end of the red arrow from Steuart’s Brigade and the Baltimore Pike.

(courtesy of CWT)

And in the darkness, just a short 500 yards from where the attack wound down in the darkness, stood the vital Baltimore Pike. Filled with supplies and reserve artillery and providing a conduit for Union troops to move, the road was one of the critical arteries needed to be defended by the Union army. Granted one brigade could never have held the road for any extended period of time yet a temporary hold or just the appearance of Confederate soldiers would have caused a stir. Darkness, though, shielded that possibility, leaving what would have happened to scores of historians in decades to come to discuss.

How close were the Confederates to that pike in actuality? Goldsborough opined that the rebels were only 600 yards and that when Steuart and Johnson visited his section of the line, he and the two generals stood hearing traffic on the Baltimore Turnpike. Johnson made note of it but rode away. Another of those “what-ifs” from the Battle of Gettysburg now occurred because at this late time in the night and no further word from Johnson, any emphasis for an attack also waned.

As Goldsborough and the 1st Maryland Battalion went to sleep that night, they, with the rest of the brigade could recount with pride that they held an advanced position within the enemy lines. But, what was disconcerting was they had launched their assault too late in the day and came up just short of reaching the critical roadway needed by the Army of the Potomac. Darkness did not stop, however, the scattering fire of the two antagonists interspersed on Culp’s Hill. Morning would bring the renewal of heavy fighting and for those Southern soldiers hailing from Maryland, the chance to march back to their beloved state victorious down the pike that bore the name of a city of such symbolic pride.

However, they were only 500 yards.

That was nice. I thought there would be more comments about the “poor” showing of German-American troops holding the right flank of the Cemetary Ridge. They almost broke, which would have been the rolling back of the whole Cemetary Ridge and Culp’s Hill being outflanked on the Union troop’s left flank.