Williamsburg’s Dividing Line

Today, we are pleased to welcome back guest author Drew Gruber.

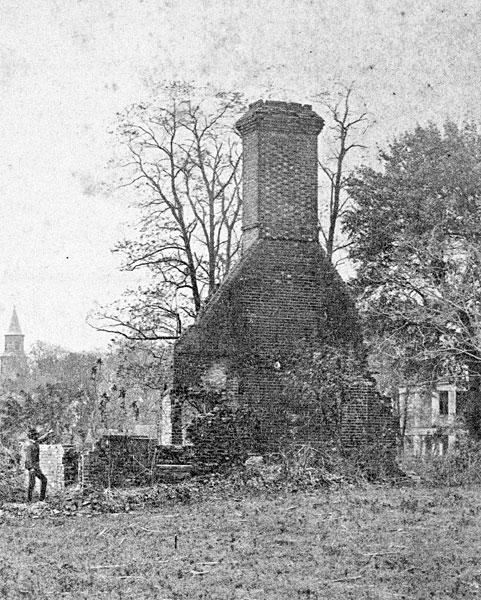

As Rockefeller’s team began the great restoration of Williamsburg to its appearance in the colonial era, most of the town’s newer structures were razed. However, 88 original 18th century buildings were preserved, providing the literal foundations for today’s venerated historic area. In doing so, Rockefeller inadvertently provided our community with a largely intact urban landscape in which the Civil War’s lesser studied dramas played out. Williamsburg’s streets, residents, and sentinels experienced the realities of war behind the lines including partisan raids, martial law, inflation, and the effects of the Emancipation Proclamation.

On the eve of the Civil War, Williamsburg was a quiet, almost forgotten Tidewater town whose heyday had passed with the armies in 1781. However, of the 1,900 residents recorded by the 1860 census about 750 were enslaved.[1] With most able-bodied males having enlisted after 1861, Williamsburg’s population consisted of women, the enslaved and inmates of the Eastern Lunatic Asylum. While the vast majority of the town was less than thrilled to host the invading army, Williamsburg’s enslaved population was both excited and nervous—having the most to gain or lose depending upon the war’s outcome.

With the exception of a few scattered days and during the 1863 Siege of Suffolk, Williamsburg was continually occupied by Union soldiers from May 6, 1862 until September 1865 who inadvertently provided a refuge, albeit a tenuous one, to the region’s slaves. While some of Williamsburg’s enslaved population made their way to the camps at Yorktown and Fort Monroe, the majority initially stayed behind, providing an asset to the Union garrison. Making the best of this free (and idle) labor source, Union authorities frequently utilized local slaves in fatigue and engineering projects. With their future uncertain at the ‘colored camps’ as well as with the Union army’s reverses in 1862, slaves on the Peninsula were in a frenzied state—but they weren’t the only ones on edge. For the Union soldiers who policed the town, the war on the home front was a less glorified, yet equally dangerous assignment. Besides the relative safety and comfort of the quarters at Fort Magruder, Williamsburg was not a hospitable place. Venturing past the College of William and Mary, by even a few dozen yards, could be life-threatening with Confederate units controlling the ‘no man’s land’ between Williamsburg and Richmond. It was suspected that white residents coordinated with the partisans just outside of town, providing them the information then needed to harass Union operations on the Peninsula. To complicate matters further, Union Provost Marshall David Cronin mentioned the likely espionage of both a mulatto man and a free black couple in Williamsburg who frequented Union headquarters and likely aided the Confederate raiders. [2]

Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation added a new dynamic to the complicated situation at Williamsburg. Besides policing an unruly white citizenry and an anxious garrison, officers like Cronin now had to interpret the ramifications of sweeping legislation to several hundred formally enslaved people. The proclamation which freed slaves in areas currently in rebellion included a list of exceptions. York County, Virginia was included in the exceptions and this fine print is worthy of a closer examination.

Walking down today’s Duke of Gloucester Street, visitors roughly follow the dividing line between James City County and York County as it existed in 1863. James City County, on the south side of the street, continued west, past the College into Confederate territory, and included roughly half of the town’s residences and businesses. The section of town on the north side of the street, however, was within York County. This jurisdiction continued east, past Fort Magruder toward Yorktown and was squarely within Union control. This municipal line, which was now cited in an executive order (which freed slaves on one side and left slaves on the other in bondage), was by no means enforceable or practical due to the nature of Williamsburg’s built environment.

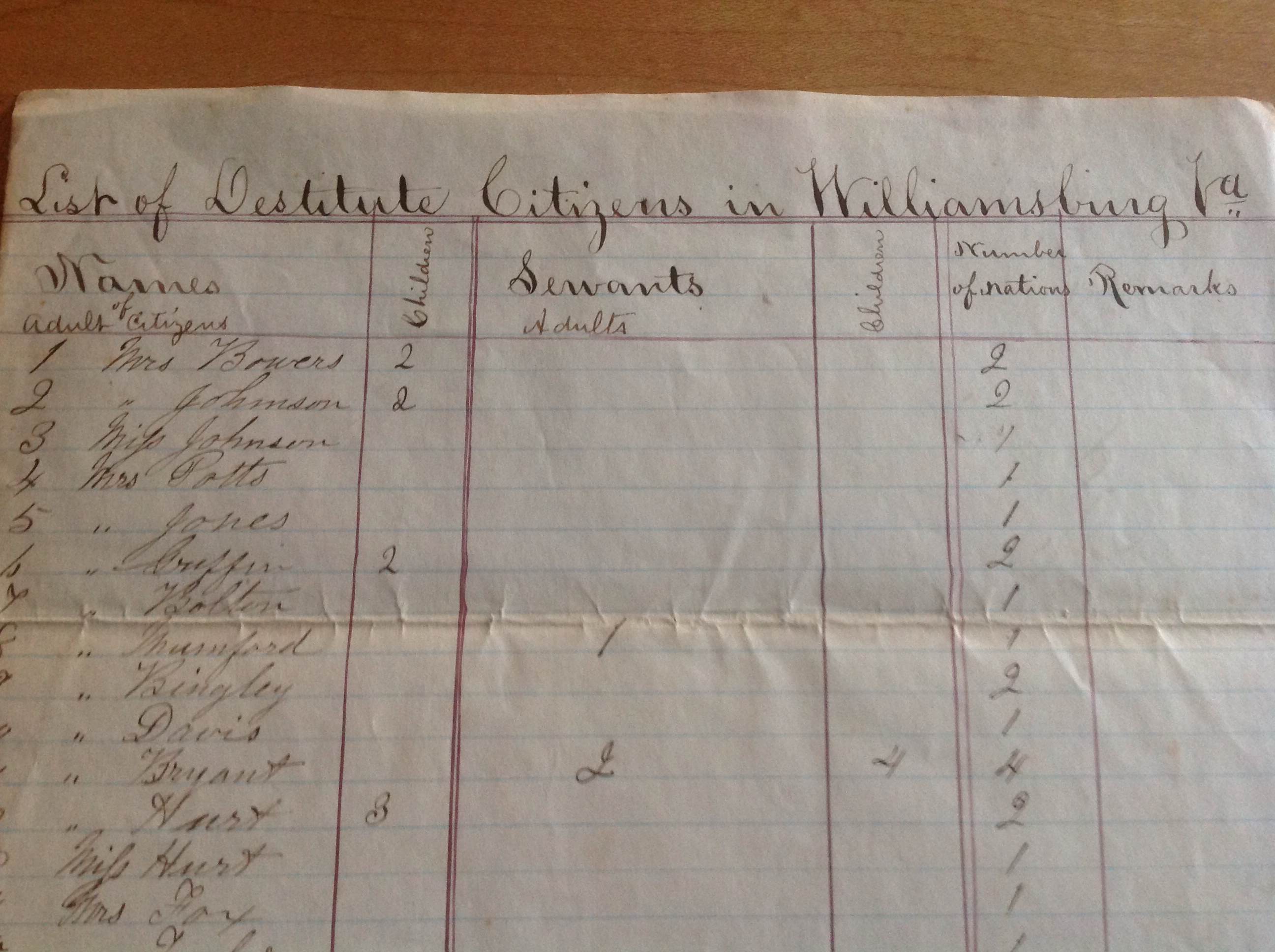

A second Confederate raid into town in March of 1863 proved to the remaining inhabitants that despite Lincoln’s decree, actual emancipation was far from certain. Union General Busteed, in an attempt to better control the increasingly volatile situation issued an order revoking the ability of residents to buy and sell goods. Additionally, he required residents to swear an oath of allegiance and limited their ability to travel into and out of town.[3] The combination of orders effectively curtailed the ability of white and black residents to access ample food stuffs and dry goods. Still a large number of white residents refused to sign an oath and by the middle of 1863 a list of “Destitute Citizens” was recorded at Union headquarters. This list documents the 95 white residents and 29 slaves who drew 119 rations from the quartermaster stores. [4] While it is not known how many of Williamsburg’s 750 slaves gained their freedom prior to 1865 or how many joined locally raised United States Colored Troops, the list of “Destitute Citizens” provides a rare insight into 29 slaves who remained in the war-torn town.

Despite all these challenges, Lincoln’s vision was slowly coming to fruition. Historian Carson O. Hudson has asserted that “the validity of the proclamation within the city’s limits was questionable, but evidence suggests the provost marshal liberally interpreted the decree and considered all the slaves in the area free.”[5] Walking Williamsburg’s historic area today we are able to interact with the spaces and places where the war on the home front took place. In this instance, it offers an intimate study of the Emancipation Proclamation—just scratching the surface of the myriad dramas which played out in this old Colonial Capitol.

[1] Eighth Census of the United States and the 1860 Census of Virginia.

[2] David Edward Cronin, “The Vest Mansion…1862-1865.” Earl Gregg Swem Library, Special Collections.

[3] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series 1, Volume 18. Chapter 30, Page 204.

[4] Manuscript is in a private collection.

[5] Carson O. Hudson. “We Bow our Heads to Yankee Despotism.” Colonial Williamsburg Journal, Summer 2000.