Ed Bonekemper’s Lost Cause Fact-Check (part two)

Part two of two

Part two of two

During his adventures traveling the country, talking to Civil War groups, Edward Bonekemper III kept encountering the same Lost Cause quandary. “I continued to speak to well-informed groups of people and was surprised by the great number of them who didn’t have all the facts,” he says. “In particular, I was surprised by the number of them who still believed the Civil War was caused by ‘states rights,’ not by slavery or white supremacy. I decided, ‘I have really got to dig into this question.’

“The fact that there has been this ongoing Confederate flag controversy—not just this past summer but for the past few years—provided a good reason to look into it,” he added.

Bonekemper began his investigation by framing his research questions: “What did the Confederacy stand for? What was the myth of the Lost Cause and what aspects of it deserved deeper probing?”

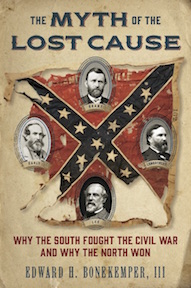

His new book, The Myth of the Lost Cause: Why the South Fought the Civil War and Why the North Won, lays out a series of questions that derive one from the next:

- What Was the Nature of Slavery in 1861?

- Was Slavery a Dying Institution?

- Was Slavery the Primary Cause of Secession and the Civil War?

- Could the South Have Won the Civil War?

- Was Robert E. Lee One of the Greatest Generals in History?

- Did James Longstreet Lose the Battle of Gettysburg and Thus the War?

- Did Ulysses S. Grant Win the Civil War Simply by Brute Force and Superior Numbers?

- Did the North Win by Waging “Total War”?

“There are probably 100 smaller issues you could identify,” he admits. “But here are the primary tenets of the Lost Cause as I understand them.”

To answer his questions, he began peeling back a century and a half of confusion, supposition, and conventional tradition. “What were the facts at the time of Secession and founding of the Confederacy?” he asked.

Doing so, he says, immediately debunks the idea that the Civil War was about states rights, not slavery.

“The myth suggests that slavery was this benevolent institution. Whites were looking out for blacks, who couldn’t rise above the level of being slaves,” he says. “Then there’s a counterargument made—that is, I think, conflicting with that—and that’s that slavery was on its way out.”

Bonekemper says evidence from the time suggests otherwise: “Slave prices were on the rise. Cotton prices were on the rise. Southern values of assets related to slavery were on the rise. Slaves were working in mines and factories, not just on farms—it wasn’t on its way out. Southern leaders talked about having $4-6 billion in slave property that had to be protected.”

Examining slavery took him to his next question: How did Secession and the formation of the Confederacy become necessary?

“The myth says that it was states rights and certainly not slavery or white supremacy,” he says.

But if “states rights” was the issue, then why did only slave states secede, he asks, pointing out that “The secession resolutions of six of the first seven states cite only slavery-related issues.” (His book offers plenty of specific examples.)

The Lost Cause then suggests that the South’s fight was a forlorn hope, doomed to fail in its good fight against a better-equipped, numerically superior foe. “Brave soldiers and brave officers did the best they could with what they had,” Bonekemper explains.

That doesn’t match up against one of the South’s most important advantages, though: its sheer geographic size. Because the North had to conquer the South, a stalemate would have been a Southern victory. But instead, Bonekemper says, the South, under Robert E. Lee’s leadership, squandered its manpower, gambled, and lost.

The myth puts an extreme focus on Gettysburg as the major battle of the war—and on James Longstreet as the man responsible for the Confederate loss. Bonekemper says the postwar attacks on Longstreet—the scapegoat—consisted of blatant falsehoods and are insufficient to get Lee “off the hook” in light of all the errors the army commander committed at Gettysburg.

Bonekemper’s previous work has criticized what he calls “the deification of Lee.” A corollary of that process is the tearing-down of Lee’s chief opponent, Ulysses S. Grant. “The other side of that is that Grant only won by brute force and sheer numbers,” Bonekemper says. “The myth is that he was a butcher. There are other Grant myths—that he was a drunk, that he was a failure—but that’s the main one.”

Bonekemper decided to pit the generals head to head in a statistical analysis—something he was surprised no one had done before. “How effective was Grant?” he asks. “How effective was Lee?”

He was amazed at what he found.

Grant commanded five armies in three theaters (Tennessee, Mississippi, and Virginia). During his tenure, his armies sustained 154,000 casualties while inflicting 191,000 casualties among his opponents. That’s a net in Grant’s favor of +37,000.

Lee, by contrast, commanded one army in one theater—“which he lost,” Bonekemper points out—sustaining 209,000 casualties while inflicting 240,000 casualties among his opponents. That’s a net in Lee’s favor of +31,000.

“Those numbers demonstrate how erroneously Lee conducted his activities,” Bonekemper contends. “The South suffered a 3.5-to-1 numerical disadvantage among men of fighting age, yet Lee was fighting like he was a Union general with unlimited resources—at a time when he needed to be defensive, when the South needed to be defensive strategically and tactically.

“Time and time and time again Lee launched frontal assaults that were massively damaging to his troops,” Bonekemper says, rattling off examples: Start with the week of attacks in the Seven Days campaign. Then there’s Chancellorsville, where most people think of Jackson’s Flank attack, but for the rest of the time, Lee launched frontal assaults. “At Gettysburg, days two and three of the battle were nothing but a long nightmare of frontal assaults,” he says. “One could even make the argument that in the Wilderness, Lee was as much of an attacker as Grant was.”

Premise by premise, Bonekemper uses historical evidence to eviscerate the mythology. “All that I can do as an individual historian is go back to the original evidence,” he says. “What were the demographics? What were the slave prices? What did the Confederate constitution say? How did the South behave? What about the South’s failure to assure potential foreign allies that slavery and the illicit foreign slave trade would be ended? What about their non-use of black troops? What about their refusal to take part in one-on-one prisoner exchanges involving black troops—which would’ve been of great benefit to the South?”

Bonekemper surprised even himself with his findings. “It seems as though the Confederacy became more concerned about preserving slavery than winning the Civil War,” he says, “which is pretty mind-boggling!”

His book will, no doubt, stir controversy, and Bonekemper acknowledges that there will be some willful resistance to the facts he presents: stubborn as those facts might be, devotion to the Lost Cause can be even more so. “In many ways, that myth has been America’s most successful propaganda campaign,” he’s conceded.

Thanks Chris. The above is a very readable summary of Bonekemper’s important book and caused me to order it. Would it be worth a conference of its own?

Bonekemper just another in an ever growing number of revisionist historians bent on re-writing history to fit a PC agenda. Slaves were property, legally held. The war was fought over Constitutional issues regarding restriction by the Federal Govt. of a US citizen’s right to do with his property as he saw fit. The South’s right to secede was no different than the colonials right to secede from the British Empire. The only difference? The South lost and winners write the history of war.

Your oversimplification overlooks the fact that slaves were not just property but people, and focusing on the legal angle sidesteps the inconvenient moral implications of that. At least your own logic does lay out slavery as the cause of the war, which some people still try to ignore altogether.

The war was fought over the right of states to secede from the Union. Secession was due to the southern states seeing that, in the long term, if they stayed as part of the USA, free-states would gain eventual numbers to amend the Constitution and outlaw slavery. They also misrepresented Lincoln’s stated positions that the was not intending to impact slavery in existing slave states. Although the south fired the first shots at Fort Sumpter, they were not intending to start a war, just to evict what they now regarded as a foreign power (i.e., the USA) from occupying a fort in their territory. The moral issue of slavery was an issue that many southern gentlemen (including George Washington and Thomas Jefferson) wrestled with, but were reluctant to part with the wealth that their slaves, as property, represented. Too often the cause of secession and the cause of the war are mistakenly assumed to be one and the same. Robert E. Lee, for example, opposed secession. But once his home state, Virginia, voted to secede, his loyalty to his state caused him to resign from the US Army.

South Carolina initiated the attempted violent overthrow of the United States government.

South Carolina seceded most directly in response to the election of Lincoln. The consequent taking of federal assets was an act of rebellion and crime. Whether an act of war debatable only in light of US refusal to confer national defectionstatus to the Confederacy. The de facto war started with the siege of Sumter.

Lincoln in his wisdom understood the illegitimacy of secession thusly: a state of the Republic will abide by the outcome of a national election. If the unpalatable result, of a lawful plebescite, be grounds for breaking the union, the experiment will have failed.

Is the notion that all white Southerners supported secession one of the “smaller issues you could identify”. Revisionist histories like those of Thomas Woods never mention Southern Unionists in such regions as:

— the Appalachian highlands from Maryland to Georgia

— the “Quaker Belt” of the North Carolina Piedmont

— the Kentucky/Tennessee/Alabama “Highland Rim”

— the Ozarks of Arkansas and Missouri

— the “Missouri Rhineland” west of St. Louis

— the German Hill Country of Central Texas

It’s hard for me to think that opposition to secession in those regions had no impact upon the South’s ability to win the Civil War. This opposition meant that three hundred thousand slave state whites were fighting (or were provoked by the slaveowners or Lincoln into fighting) for the North – turning the South against itself!