The man in the corner…

Colonel Anson Stager is not exactly a household name, even to many students of the Civil War.

If your reading has taken you into the arcana of military codes, or if you are a fan of late 19th Century industrialization, you probably have heard of him: he was an instrumental figure in both arenas. He not only invented the primary cipher adopted by the Federal armies during the War; he was also the first Superintendent of Western Union, and at various times, president of the Western Electric corporation, Chicago Telephone, and the Western Edison Company. He died in 1885.

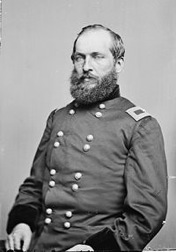

For me, however, his name first popped up in the context of an important interview between James A. Garfield and Union Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, a meeting which occurred on October 20, 1863.

Stanton was seeking details – some might say dirt – concerning the actions and behavior of Garfield’s boss, Major General William S. Rosecrans, during and immediately after the battle of Chickamauga. Rosecrans, you see, was driven from the field before the battle’s close, and rode back to Chattanooga, 12 miles distant; leaving George H. Thomas to continue the fight alone.

Garfield (along with fellow general James B. Steadman) met with Stanton at Louisville, Garfield having left the Army of the Cumberland to take up a seat in Congress. In the wake of the Chickamauga crisis, Stanton rushed west from Washington to secretly confer with Ulysses S. Grant. Stanton offered Grant command of the entire Western Theater, which position Grant accepted.

Though the Grant-Stanton meeting had already occurred, and the order relieving Rosecrans already publicly announced, in time Rosecrans and his supporters would come to believe that Garfield’s testimony now decided his commander’s fate. Garfield, it was whispered, betrayed his old commander, suggesting that Rosecrans lost control of his emotions, and was unfit to retain his command. This testimony supposedly went far towards cementing Stanton’s opinion that Rosecrans had to go.

That last was certainly true: Immediately after the Garfield meeting Stanton wired as much to President Lincoln. Garfield’s “representations,” asserted Stanton “more than confirm the worst that has reached us as to the conduct of the commanding general. . .”

Garfield would go to his grave insisting otherwise. Far from betraying Rosecrans, he instead did he best to defend his commander against Stanton’s hostile accusations. In 1880, Garfield protested to Rosecrans that when Stanton “denounced you . . . I rebuked him and earnestly defended you against his assaults.”

How could that be? Who was right? Garfield would tell his friend and fellow Ohioan, Brig. Gen. Jacob D. Cox, that Stanton – a veteran courtroom lawyer and prosecutor – “not only had dispatches full of information from General [Montgomery C.] Meigs, who now also met with him at Louisville, [but also] . . . [Assistant Secretary of War Charles A.] Dana’s . . . series of cipher dispatches giving a vivid interior view of affairs and of men.” As a result, Stanton demonstrated “such knowledge of the battle . . . that it would be impossible for Garfield to avoid mention of [those] incidents which bore unfavorably upon Rosecrans.”

In short, Stanton was not merely fact-finding. He cross-examined Garfield – and like any good trial attorney, asked no question to which he did not already know the answer. The question remains, however: was Garfield a hostile witness, or a friendly one?

Three other men were present at this meeting. Steadman; Military Governor of Tennessee Andrew Johnson, and the aforementioned Colonel Stager. Neither Steadman nor Johnson left accounts of this meeting.

But what of Stager? In 1881, one of those Rosecrans supporters, Colonel Francis A. Darr (formerly a staff officer for George Thomas) claimed to have met Stager the previous year at West Point’s annual military exercises, where, as Darr related privately to Rosecrans, Stager claimed that “Garfield . . . denounced Rosecrans as incompetent, unworthy of his position, as having lost the confidence of his army, and should be removed.” Darr’s quotation would seem to settle the matter pretty conclusively.

Sort of.

Legally speaking, Darr’s statement is hearsay, second-hand information. But we sit in the court of history, not of law. Darr’s statement has been used extensively by historians – most notably, Rosecrans’s biographer, William Lamers – as clear-cut proof of Garfield’s duplicity.

Even that much might not have come to light if not for the fact that in 1880, James A. Garfield became the quintessential dark-horse candidate for President, winning the election, only to be struck down by an assassin the next year, dying shortly thereafter. Election pressures in 1880 made the controversy between Garfield (the Republican nominee) and Rosecrans (running as a Democrat for congress) into headline news. As the rhetoric heated up, Rosecrans took to repeating Darr’s assertions in his public comments. Garfield’s subsequent death only gave the controversy greater legs. Well into 1882, newspapers were reprinting stories about Garfield, Rosecrans, Stanton, and, inevitably, Stager.

By then, Garfield was dead, and beyond any hope of refutation. Stager was anything but. A respected businessman and public figure in his own right, Stager was living in Chicago. Naturally, the press turned to him for comment. In the June 15, 1882 issue of the Chicago Daily Tribune, when asked about Rosecrans’s statements, Col. Stager replied “that it is not in fact true that he [Stager] told Gen. Rosecrans or anyone else that what occurred at the Louisville meeting with Stanton was the reverse of what was stated by Gen. Garfield.” Stager further asserted that he never even met Rosecrans at West Point.

When it was clarified that Rosecrans was not claiming to have met Stager personally, but instead quoting Francis Darr, Stager appeared in the June 17 edition of the Tribune; giving an even more emphatic denial. “‘I never made any such statement,’ said Gen. Stager . . . ‘to Gen. Darr or anybody else. It wasn’t a fact – Gen. Garfield did not denounce his superior officer – and I couldn’t therefore have said he did. I met Gen. Darr at West Point; but if he says I made such a statement he misapprehended me.'” Stager’s comments spread, via the wire services, to a few other papers – as far away as Sacramento, for example. But though they seemed to get widespread play for a while, as the controversy faded, so too, did Stager’s rebuttals.

For decades, Darr’s version of events has been widely cited as corroborating Garfield’s duplicity. Stager’s denials are very strong evidence that in fact, Garfield was right all along: Far from denouncing Rosecrans, Garfield defended him.

Was Darr confused, mistaken, or being duplicitous? How about Stager? Did Stager say one thing in private and another in print, for public consumption? At this remove, who can be sure? But at the very least Stager’s public statements cast much greater doubt on the question of Garfield’s supposed treason.

William Lamers’s outstanding biography of William S. Rosecrans was first published in 1961. Lamers mined the voluminous Rosecrans Papers extensively, which is where he found the Darr letter. He plumbed a wealth of other sources as well; the Chicago Tribune among them. What he lacked, of course, were the tools of a more modern age – the combination of search engines and digitized, online newspaper databanks that place millions of articles at our fingertips.

With these tools and the right search parameters, researchers can now reduce the endless hours once required to comb newspaper (and other) archives to mere minutes. That ability leads to some fascinating discoveries.

I suspect that there are a great many more such interesting items waiting to come to light.

Great story Dave! I just finished reading Dan Vermylia’s book “James Garfield and the Civil War” so very relevant. It sounds like Dana did the most damage.

My own sense is that Garfield was more loyal than not to Rosecrans. However letters written by Emerson Opdycke after Chickamauga seem to show that Opdycke’s changing opinion of Rosecrans was influenced by things he was told by Garfield and Dana. Pages 99, 101, 115-117 of the book To Battle for God and the Right give examples of this https://books.google.com/books?id=a3CT_V65hG8C&pg=PR11&dq=emerson+opdycke+letters&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjm5a_JmpPMAhWIOj4KHRtNC3oQ6AEIHDAA#v=onepage&q=emerson%20opdycke%20letters&f=false

it is interesting that Garfield gave a forceful speech on the floor of the House of Representatives defending Rosecrans in February 1864. Also important is his response to a question from NY Tribune editor John Russell Young in 1867 in which he said political leaders were “not unwilling to see evil befall him [Rosecrans]” before Chickamauga. Dana stirred up much of the anti-Garfield talk in his NY Sun newspaper. This was done before Dana’s own correspondence with Washington was first published in 1882. Until Dana’s role was made public opinions expressed were based on incomplete knowledge. Certainly Dana’s role was far more more damaging to Rosecrans than Garfield’s Still in the words of a Garfield biographer .”Garfield’s friendship for Rosecrans was stained by a deception that no kind acts or words could wash away.”

I have been reading up on the relationship between Garfield and Rosecrans. It is very complicated. I tend to think Garfield was conflicted, basically loyal to Rosecrans, but also knew his stock in Washington was falling and he was not going to go down with the ship. I do wonder how the relationship would have played out had Garfield lived longer.

It is interesting and important to know that Garfield offered the vice presidential nomination to Rosecrans on the Union (Republican) ticket in 1864. Surely in 1864 whatever doubts Garfield may have had about Rosecrans in the fall of 1863 were resolved. By 1880 when they were both candidates for elective office their relationship had been strained by the allegations fanned by Dana that Garfield had been disloyal to Rosecrans in 1863. Garfield had been somewhat disloyal writing to Chase behind Rosecrans’ before Chickamauga back but Dana claimed he had a letter written after Chickamauga by Garfield. That letter was never produced. The fact that Garfield and Rosecrans were from different parties didn’t help things and led to Rosecrans making a comment about candidate Garfield that resulted in the final break of their friendship. Had Garfield lived it is possible that Rosecrans’ military reputation would have been strengthened by President Garfield. There would have been no reason for Garfield to disavow what he said about Rosecrans on the House floor in February 1864.

Actually, I am not convinced that Garfield was being deceptive at all. I am having trouble finding any real evidence of it. I think Dana is pretty clearly a proven liar. His attempts to smear Garfield aimed at a dual objective – to divert attention from his own duplicity and as a political hit-job on Garfield on behalf of one of his own political benefactors. The evidence via James R. Gilmore is equally unreliable – Gilmore’s various versions of the dinner party story are contradictory, refer to the same spurious letter Dana alluded to, and all appeared decades after most of the principals were dead.

There are many, many reasons to doubt the charge. So much so that I ended up devoting an entire 40 page appendix to the question of Dana-Rosecrans-Garfield in Volume 3 of the Chickamauga Campaign.

good and interesting story . On a side bar if you can , visit the NPS site in n.e. ohio dedicated to Pres.Garfield

Correspondence published in Society of the Army of the Cumberland, Burial of General Rosecrans, Arlington National Cemetery, May 17, 1902 (Cincinnati: Robert Clarke, 1903), pp. 89–97 makes it pretty clear that Garfield had denounced Rosecrans’ generalship.

Montgomery Blair, “in answer to this paragraph: ‘General Garfield’s letters stated that General Rosecrans had fled from the field during the battle of Chickamauga, and that the confidence of the army in him had been broken, if not destroyed,’ says: ‘This was the purport of the statement on which Rosecrans, was removed—which was combated by me and Chase—and which Lincoln told me had been verified by Garfield. Garfield was one of a large dinner party given by my father, subsequent to the removal of Rosecrans, at which Governor Dennison and my brother General Blair were present. There may have been another member of the Cabinet present beside myself, but I do not recollect the fact. Dennison, I recollect, condemned strongly the removal of Rosecrans, and there was a general concurrence of all present in his views, and I recollect that Garfield especially was loud and pronounced in condemning the act. I was of course very much astonished at his duplicity.” [Garfield seems to have picked up some pointers from Stanton about stating opposite opinions to different groups of people.]

In the Boston Globe of June 14, 1882, Rosecrans indicated that he believed that Garfield had been duplicitous.

Another unjust detractor of Rosecrans’ actions at Chickamauga, at least after the war if not during it, was W.F.G. Shanks in his Recollections, pp. 265-66: “The engagement itself was the worst managed battle of the war. The public blamed Rosecrans, and the President relieved him for leaving the field and retiring to Chattanooga, but it is not generally known that Rosecrans never saw the battle-field of Chickamauga; yet such is the fact ; and he has to this day no knowledge of the roads or configuration of that field from personal examination. He did not actually see a gun fired on that field except when Longstreet broke McCook’s corps and pushed through Rosecrans’s quarters, which were in the rear of that part of the field.”

Joseph. “The Burial of General Rosecrans” article is by James R. Gilmore, and is a variation of an article he published several times with various papers, starting in the 1890s. Gilmore’s key evidence is the same as Dana’s – the supposed post-Chickamauga letter to Chase which Chase is supposed to have either read out loud to the cabinet or shown to Lincoln. That letter is a fabrication, and Gilmore should have known it by the time he was writing. I find Gilmore to be very unreliable in his various accounts, so much so that I think he made it up. He was, after all, famous for his fiction.

Blair’s commentary is equally problematic – it is all second-hand, from Blair’s POV, and then related to us 3rd-hand via Gilmore.

There is no question that Rosecrans believed Garlfield’s perfidy, but that is not actual proof of anything except that Rosecrans was duped by the propaganda of the Stalwart wing of the Republican Party – which railed hot and heavy against Garfield, a progressive. Finding real first-hand evidence of Garfield’s duplicity that has not been filtered through the pen of either Dana or Gilmore – both of which are demonstrably false in their own versions of the whole affair – is what I am after. It isn’t there. Given your willingness to re-examine the record when it comes to Grant, you can appreciate how much false history can arise from such “filters.” Dana and Gilmore are highly suspect.

Stager was my one unimpeachable source, admittedly via Darr. But I could find no evidence of Stager being caught up in the political currents that would lead him to denounce Garfield. And then, lo an behold, I find Stager himself saying the exact opposite.

Finally, I relied on Shanks for much, since he witnessed much, but he was a man who let his biases show. This passage concerning Rosecrans is complete nonsense. Of course Rosecrans saw the battlefield. He rode the length of it on September 20. Was he in the front lines the whole time? Of course not. But to claim he “never saw the battlefield” or “had no knowledge of the roads from personal examination” is simply not true. Shanks was a radical Republican, and viewed Rosecrans as a political; enemy for his Democratic views. He performed a hatchet job on Rosecrans whenever he could.

As to Blair’s quotation on page 96 of “The Burial of General Rosecrans” (Garfield’s letter described a fleeing Rosecrans and it was this “statement on which Rosecrans, was removed . . . which Lincoln told me had been verified by Garfield”), Page 352 of Larry J. Daniel’s “Days of Glory: The Army of the Cumberland, 1861-1865” mentions Blair’s post-war affidavit that confirmed Garfield’s letter to Chase had been read before the cabinet. Does Welles’ diary have anything to add?

I certainly don’t put much stock in Shanks’ “unjust” detractions, but I’m also not sure how much Shanks based his reporting on political views compared to his other biases. I don’t think that he was the enemy of either General Grant or Sherman and they certainly weren’t radical. How true is Shank’s claim that he had determined by the morning of September 19th that Longstreet’s two divisions had arrived and that he vainly informed Rosey? It doesn’t seem that likely.

The problem with Blair’s evidence is that A) he wasn’t present when the supposed letter was read, he got that second-hand, B) it is pretty clearly established that there was no letter from Garfield to Chase describing a fleeing Rosecrans (that was the Dana invention) and C) the orders relieving Rosecrans were received in Chattanooga a full day before Garfield had his interview with Stanton. Blair’s account is just full of holes. He heard it from a guy, etc.

Welles and Chase’s Diaries are completely silent on the issue. They record no such reading of any letter before the cabinet, all or part.

Shanks hated Rosecrans. As for the Longstreet claim, yes, he knew that Longstreet’s troops were on the field. He got that from army HQ, however. The part where he claims he tried to inform Rosecrans and was rejected is patently untrue.

Dave,

Thanks. I wasn’t aware that Shanks hated Rosecrans. That would tend, of course, to make the bond between Grant and Shanks that much stronger. I knew that Shanks had trouble telling the truth, at times.

Right after the Battle of Chattanooga, Shanks told of seeing a copy of Grant’s letter to Thomas several days before the battle detailing plans to raise siege “and get possession of all-important Lookout Mountain . . . .” “It was supposed the enemy would defend Tunnel Hill with vigor. Lookout could be held by a small force. Gen. Grant held that, to attack his flanks vigorously, in order to force him to keep his lines lengthened, and thus weakened, would afford a favorable opportunity to test the strength of the centre.” It was decided that Sherman should take 3 divisions of own army with Davis. Hooker was to use Geary, Osterhaus and 2 brigades of Stanley’s to hold rebels there, but being authorized take Lookout if possible. Thomas was to hold Granger and Palmer well in hand in the centre until Grant gave orders to strike. All of this is patently untrue. Either Grant fabricated this order and Shanks was wrong about the date, Shanks was deluded, or Shanks fabricated this order.