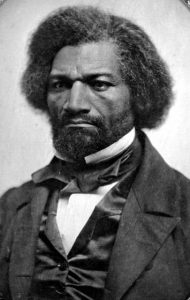

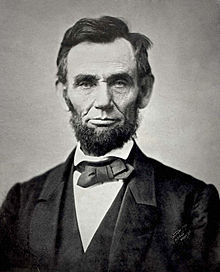

Did Frederick Douglass Influence “The Blind Memorandum”?

The timing. The national circumstances. The reports of what two great men discussed. It raises the question: did Frederick Douglass influence Abraham Lincoln’ decision to draft the document referred to as “The Blind Memorandum”?

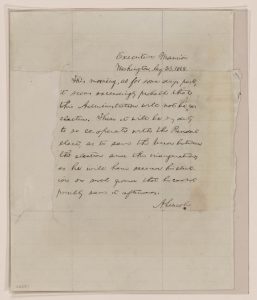

On August 23, 1864 – one hundred fifty-five years ago on this day – President Lincoln wrote a resolution, folded the paper, and somehow got members of his cabinet to sign the document without really knowing the contents. Then the paper was put away, prepared but not needed unless Lincoln lost the election that November.

The paper and written words outlined Lincoln’s resolve to save the Union, even if he lost that election:

This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly probable that this Administration will not be re-elected. Then it will be my duty to so co-operate with the President elect, as to save the Union between the election and the inauguration; as he will have secured his election on such ground that he can not possibly save it afterwards. — A. Lincoln

Restoration of the Union had always been at the top of Lincoln’s list during the Civil War conflict, and most historians have focused on the mystery and political implications of this document. They highlight the struggling military situation prior to the Capture of Atlanta, the strengthening Democrat Party at the end of summer as their platform solidified and George McClellan rallied supporters. They focus on Lincoln’s insight and resolve to reunite the country.

As I’ve been relooking at the Lincoln White House timeline, though, and some other primary sources beyond the election, I noticed the arrival of a key influencer just four days prior to the draft and signing of the Blind Memorandum.

Frederick Douglass visited Lincoln on August 19, 1864, and in later years recalled part of their discussion:

“…Every reverse to his [Grant’s] arms was made the occasion for a fresh demand for peace without emancipation, that President Lincoln did me the honor to invite me to the Executive Mansion for a conference on the situation. I need not say I went most gladly. The main subject on which he wished to confer with me was as to the means most desirable to be employed outside the army to induce the slaves in the rebel States to come within the Federal lines. The increasing opposition to the war, in the North, and the mad cry against it, because it was being made an abolition war, alarmed Mr. Lincoln, and made him apprehensive that a peace might be forced upon him which would leave still in slavery all who had not come within our lines. What he wanted was to make his proclamation as effective as possible in the event of such a peace. He said, in a regretful tone, “The slaves are not coming so rapidly and so numerously to us as I had hoped.” I replied that the slaveholders knew how to keep such things from their slaves, and probably very few knew of his proclamation. “Well,” he said, “I want you to set about devising some means of making them acquainted with it, and for bringing them into our lines.” He spoke with great earnestness and much solicitude, and seemed troubled by the attitude of Mr. Greeley and by the growing impatience at the war that was being manifested throughout the North. He said he was being accused of protracting the war beyond its legitimate object and of failing to make peace when he might have done so to advantage. He was afraid of what might come of all these complaints, but was persuaded that no solid and lasting peace could come short of absolute submission on the part of the rebels, and he was not for giving them rest by futile conferences with unauthorized persons, at Niagara Falls, or elsewhere. He saw the danger of premature peace, and, like a thoughtful and sagacious man as he was, wished to provide means of rendering such consummation as harmless as possible. I was the more impressed by this benevolent consideration because he before said, in answer to the peace clamor, that his object was to save the Union, and to do so with or without slavery. What he said on this day showed a deeper moral conviction against slavery than I had ever seen before in anything spoken or written by him. I listened with the deepest interest and profoundest satisfaction, and, at his suggestion, agreed to undertake the organizing a hand of scouts, composed of colored men, whose business should be somewhat after the original plan of John Brown, to go into the rebel States, beyond the lines of our armies, and carry the news of emancipation, and urge the slaves to come within our boundaries.

This plan, however, was very soon rendered unnecessary, by the success of the war … and by its termination in the complete abolition of slavery. [Emphasis added]

Assuming Frederick Douglass’s report of the conversation is accurate, Lincoln privately equated the promise and protection of freedom with the unity of country more strongly than in his previous statements. In the “Blind Memorandum”, the president did not specifically address the abolition of slavery – again reverting to national reunification – but he wrote about making changes in such a way that any Democrat president could not undo the Lincoln administration’s progress.

Can we speculate that Lincoln’s plan for restoring the Union swiftly and irrevocably in the four months between election results and a successor taking office would likely have included steps to ensure freedom for those still in bondage? It seems quite possible. Douglass’s insight into the conversation just days before August 23rd hints that Lincoln had more than reunion on his mind.

Doris K. Goodwin explains in her study Team of Rivals that Lincoln realized a Democrat presidential victory would likely trigger “an immediate compromise for peace. Slavery would thus be allowed to remain in the South, and even independence might be sanctioned.” (page 648) She follows this statement with explanations of other interviews and primary source quotes revealing that Lincoln “was considering every possible means by which the Negro could be secured in his freedom.” (page 648) In the following days after his interview with Douglass, Lincoln continued to put forward his belief that slavery must end and in one letter, he wrote: “There have been men who have proposed to me to return to slavery the black warriors of Port Hudson and Olustee to their masters to conciliate the South. I should be damned in time & eternity for so doing.” (page 651)

Did Frederick Douglass directly influence Lincoln’s “Blind Memorandum”? The answer cannot be stated either way with emphatic certainty. However, we can conclude that Lincoln sought Douglass’s advice and expressed a strong feeling that freedmen should not be returned to bondage and those enslaved still within states in rebellion should be made aware of their promised freedom. According to Douglass, Lincoln had placed freedom on a more equal platform with unity than ever before. In his written, secretive document, Lincoln made his promise to make it difficult for a successor to agree to a peace that would divide the nation and – by default – allow slavery to continue.

Looking back on this history with the knowledge that Lincoln won the 1864 Presidential Election, it can be easy to overlook the implications of the uncertainties he faced and the bold, secretive steps he pursued to redefine the nation even if he was forced from the executive office. Frederick Douglass had tirelessly pushed Lincoln toward a promise of freedom, and by August 1864, he felt certain such a guarantee ranked high in the president’s thoughts for the political future of the country.

Sources:

“Lincoln’s Blind Memorandum,” by Erin Allen, Library of Congress. https://blogs.loc.gov/loc/2014/08/abraham-lincolns-blind-memorandum/ (Accessed on August 20, 2019).

Douglass, Frederick. Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. Available online at “Documenting The American South” at University of North Carolina. Pages 434-436. https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/dougl92/dougl92.html (Accessed on August 22, 2019)

Goodwin, Doris Kearns. Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. New York, Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2005. Pages 648-653.

Blight, David W. Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom. New York, Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2018. Pages 436-437.

As regards the meeting between President Lincoln and Frederick Douglass in August 1864, I believe you are correct in your assumption: something substantial was discussed at a time when Lincoln was uncertain of the result at Atlanta, and concerned with the imminent November election. Also need to keep in mind: this was the Second meeting at the White House between these two men. The first occurred a year earlier, about August 10th, and marked a departure from Lincoln’s policy of keeping Frederick Douglass at arm’s length (due to the fact Douglass had been a financial supporter of John Brown; and Republicans had denied ANY direct involvement with Brown.) That first meeting in 1863 provided Lincoln and Douglass the opportunity to discuss recruitment of Black soldiers (and how to make that recruitment more effective.) And the newspapers, North and South, barely noticed. And that August 1863 meeting set the groundwork for the August 1864 meeting.

Excellent point. Thank you for adding the 1863 notes for better context!

Just a few bits to add:

Although banished to the Confederacy in 1863, Clement Vallandigham was back in the United States (via Bermuda and Canada) in 1864 endeavoring to topple Lincoln in the November election. In the 19 AUG 1864 edition of the Evening Star (Washington, D.C.) page 2 is to be found details of Peace Campaigner Vallandigham’s recent speech at Syracuse, and stated intention of next appearing in Chicago. In the same edition of the Evening Star (page 3 col.1) is to be found a synopsis of the talk given by Frederick Douglass at Presbyterian Church, Washington (a “benefit for wounded and sick colored soldiers, given evening of August 18th” – and likely contains elements of the matters discussed by President Lincoln and Douglass on August 19). In the September 6 edition of the Chicago Tribune on Page One an impromptu survey conducted aboard a railroad car travelling through Lincoln’s Home State of Illinois revealed the following voting intentions: McClellan 91, Lincoln 75, Fremont 8, and Frederick Douglass 1 (which illustrates the valid worry Lincoln felt about November.) Finally, in “The Life and Letters of John Hay” by William Roscoe (1916) pages 216 – 217 are details of the opening of that sealed “Blind Memorandum” on 11 NOV 1864.

Excellent discussion, Sarah. Thanks.