Dan Welch: Interpreting Stonewall at Second Manassas

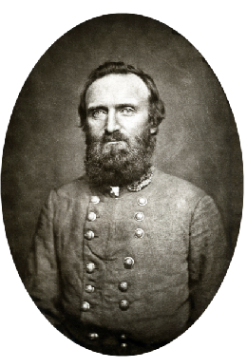

The concentration of this year’s ECW Symposium will examine great defensive stands of the American Civil War. The multi-day event will look at numerous commanders, command decisions, and battlefields along the way, including both theaters of the conflict. For me, my task will be to interpret just one of those defensive stands, “Stonewall” Jackson at Second Manassas. But how does one go about preparing or even interpreting such a large-scale action as the several day battle and put it into a confined window of time miles from the battlefield itself?

Before we can even tackle that question, we have to come to a mutual understanding of what a defensive stand is, how it works, and why it is chosen over other tactical methods of warfare such as the attack, or offensive. In its most basic definition, a defense is where a commander and his unit wait to receive the attack of an opposing force. This does not mean that at the army level, the artillery remains silent as the foe is marching towards you, or your cavalry remains in the rear avoiding further military opportunities. Simply, the main body of your force stands and waits for the foe to come to you.

Now there are many reasons a commander may choose to go on the defensive, rather than the tactically, or even strategically, offensive. First, it may be a command style. Some commanders are naturally more reserved, not aggressive, and prefer to fight defensively. Second, it may have to do with the size of the force that the commander has with him. If the commander feels that his force is smaller than his foe, prudence dictates fighting defensively. Fighting defensively, including from prepared positions, acts as a force multiplier. In military terminology, a force multiplier theoretically takes a solid fighting force number and multiples it to a larger number because the defenders are on preferred terrain, stationary, and offered cover and concealment. The idea of a force multiplier could then even the odds when the attack is received.

Yet, there are still more reasons as to why a commander may choose to fight defensively. Terrain may be one of the biggest influences. If the surrounding area provides beneficial terrain to fight defensively the commander may opt for it. The ground may provide anchors for the flanks of the unit, such as strong geographic features that do not allow them to be turned. It may also provide height, or high ground, where the unit can fight from the military crest of it. The ground may also provide force multipliers, such as: stonewalls, fences, ditches, or cuts in which to place your unit behind and fight from a prepared, partially concealed and covered position. Although there are still many other reasons to employ this tactic, or in a larger sense, strategy, we will examine just one final one here, politics. Politics has always influenced armies in the field, and the Civil War was no different. Top-ranking politicians, such as a president, or cabinet member, could have immense influence on what takes place in the field where these units operate. In this case, it may be to have those units under that influence fight defensively.

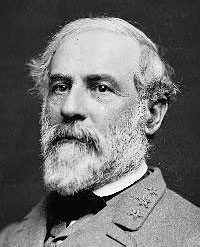

Here in this post, as well as in my presentation in August, we had to reach common ground as to why a defensive stand would be employed on the battlefield and how it works. From there, we can begin to explore the stand, in this case, that Jackson took with his corps on the former battlefield of Manassas. Before an interpretation and thus presentation of these events can occur, I need to look at as many primary sources as I can find at the command level. These sources will help me to establish why the defensive was chosen in this particular action, and ultimately, how it worked for those units on the ground that participated in that stand. The best source for this material is the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies in the War of the Rebellion, better known as the Official Records or ORs. The Official Records contain not only real-time communications in their correspondence volumes, but also official after action reports of different campaigns and battles from regimental commanders on up to army commanders. We will start at the top, with army commander Robert E. Lee.

By the time of the Second Manassas Campaign, Lee had only been in command of the Army of Northern Virginia for several months. If anything, those past months had demonstrated that at the strategic level, Lee was loathe to fight defensively. He was an aggressive commander that needed to maintain the strategic initiative as part of this command style. As we look at Lee’s report of the Second Manassas Campaign, it is clear that there were not any intentions of Jackson fighting defensively. Writing the report during the Gettysburg Campaign nearly a year later, Lee believed “that the most effectual way to relieve Richmond from any danger of attack from that quarter would be to re-enforce General Jackson and advance upon General Pope.” Certainly, language such as “advance” does not coincide with a tactical defensive stand. As Lee’s report continues,

however, it becomes clear as to why Jackson must make a defensive stand. Deep in Union occupied northern Virginia, with Longstreet’s Corps still miles to the rear, and a much larger force attacking him at Bristoe Station, “General Jackson’s force being much inferior to that of General Pope, it became necessary for him to withdraw from Manassas and take a position west of the turnpike road from Warrenton to Alexandria, where he could more readily unite with the approaching column of Longstreet.” Lee’s campaign had been offensive in nature to this point, but now with an entire Federal army boring down on Jackson’s lone corps, as Lee wrote, Jackson needed to take a defensive stand where his fewer numbers would be in a better position to push back any attacks while awaiting the arrival of reinforcements. Jackson, on the other hand, wrote differently of those moments.

Just days before the fighting at Chancellorsville raged and Jackson would be wounded, Stonewall submitted his report on the Second Manassas Campaign. Although aware, through Stuart, that Pope’s army was shifting towards him in the vicinity, Jackson did not feel the need to go on the defensive yet. Numerous times in his report with regard to the late afternoon and early evening of August 28, 1862, Jackson wrote that “Dispositions were promptly made to attack the enemy…,” and, “I determined to attack at once….” This engagement, at Brawner Farm, would be the last time Jackson’s command would be able to go on the offensive in such a significant way at Manassas. Unlike Lee’s report, Jackson made no intimation as to why he had to switch from the offensive to the defensive. Rather, he simply noted that his “…troops on this day were distributed along and in the vicinity of the cut of an unfinished railroad (intended as a part of the track to connect the Manassas road directly with Alexandria), stretching from Warrenton turnpike in the direction of Sudley’s Mill. It was mainly along the excavation of this unfinished road that my line of battle was formed on the 29th….” It was from these dispositions that Jackson’s command would receive numerous attacks from Pope’s army.

Thus, with respect to Jackson’s command having to tactically fight on the defensive at the end of that August, Lee conceded that it had to do with Jackson’s disparity in numbers against the forces in his front and the necessity to await reinforcements from Longstreet’s Corps.

But what did those numbers actually look like? Certainly the mythology of the Civil War tells us at the baser level that the Federal armies were always massive, with unlimited men and resources. The opposite can be said of the Confederate armies during the war. At this point in the campaign, Jackson’s command could fulfill the mythology’s notion. Stonewall had been hemorrhaging since the spring. The arduous Valley campaign of the spring had resulted in numerous casualties from many skirmishes and battles. The demands of that campaign had also reduced many in his ranks to combat ineffectiveness. Jackson’s Valley campaign was quickly followed by a transfer to the outskirts of Richmond and another campaign. According to former Confederate Gen. Joseph Johnston during the postwar years, writing in his Narrative, Jackson brought with him to the outskirts of Richmond “above” 16,000 troops. General Jubal Early concurred with that number. An ardent exchange on these numbers was found in the first volume of the Southern Historical Society. That number seems to align with what historian Stephen Sears estimated in his book To the Gates of Richmond.

Following the fighting of the Seven Days, and the immense casualties that the combined Confederate forces under Lee had sustained in the past month of fighting, these commands faced reorganizations in both officers and men. For Jackson it meant the formalization and expansion of his corps under Lee. At the beginning of the Second Manassas campaign, William Allan, a former colonel and chief ordnance officer with Jackson’s corps, wrote in 1880 that Stonewall’s command numbered 23,823 men. Not long into the campaign, however, Jackson and his corps fought at the battle of Cedar Mountain. In Allan’s account of the campaign in May 1880, he noted the loses at Cedar Mountain as 1,314; thus, Allan estimated that Jackson took with him 22,500 men northward towards Manassas. By the time Jackson attacked the Union column at Brawner Farm nearly three weeks after Cedar Mountain, and twelve days after Allan estimated his force at 22,500, surely that number had shrunk. For several days after Cedar Mountain, temperatures remained in the mid 90s. Although there would be several days where temperatures only peaked the 70s, most of the remainder of the month stayed in the mid-to-upper 80s. The high heat, and certain, yet immeasurable humidity, added to the weight of their gear, daily distance traveled, and heavy clothing would have thinned Jackson’s ranks considerably. No doubt if one trailed his column during their march from Culpeper County northward towards Prince William County hundreds of men, if not more, overcome with sunstroke and heat exhaustion would be found along the sides of the road. If we conservatively estimate that Jackson’s force suffered three percent of this type of casualty between August 16 and August 28, his corps arrived to Brawner Farm with 675 less men, and probably even more on the verge of collapse.

What exactly was Jackson facing in his front in Prince William County? One historian estimated that Gen. Pope’s Army of Virginia, coupled with those corps of the Army of the Potomac that arrived to the front, number 77,000. Jackson was then operating in a sphere of military influence where he was outnumbered three-to-one. Following the engagement at Brawner Farm on August 28, Pope brought his forces to bear against Jackson piecemeal. Between 8:00 am and 10:00 am only parts of Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel’s First Corps of the Army of Virginia, and a division of Third Corps, Army of the Potomac, moved against Jackson’s position, roughly 17,000 men. Jackson still maintained a numerical superiority in this scenario, not including the force multiplier that was his position. By late on August 29, more reinforcements for Pope had arrived. The remainder of the Third Corps, Army of the Potomac, approximately 10,000 men, as well as the remainder of the Third Corps, Army of Virginia, 11,000 men (less King’s division). Minus Jackson’s casualties throughout the day, the statistical data shows equal with the latest threat to his line, again, not counting the force multiplier Jackson had for his defensive position. Yet again, Pope’s newest forces on the field did not act in perfect concert, and Jackson and his men would not have to face all of these forces at once. The following day, August 30, Pope brought even more men to the field to bring against the Confederate position. Not all of these forces would be brought against Jackson in the end. With the arrival of Longstreet the afternoon prior, and later his massive assault, the numerical pressure on Jackson was partly relieved. So despite Jackson operating in a military sphere of numerical influence, the in-depth analysis demonstrates that at no time was Jackson against superior odds in his front. However, this may be a bit of historical hindsight. Jackson could not have known that Pope would not bring his entire force against him at once.

In the end, Jackson’s defensive stand held. The stories of the men that lined his position, as well as those that attempted to wrest it from the Confederate army are ones of courage, bravery, heroism, and long-odds. Join me at the Emerging Civil War Symposium, August 4-6, 2017 to hear the words of those that stood with Jackson like a stonewall at the unfinished railroad cut in August 1862.

1 Response to Dan Welch: Interpreting Stonewall at Second Manassas