Shenandoah Subordinates: George Crook and the Controversy of Fisher’s Hill

Part three in a series.

Jubal Early’s Confederates tramped through the night of September 19. After being routed off the battlefield at Winchester and chased through the town, the Army of the Valley headed south. They did not stop until they reached the prominence of Fisher’s Hill, just below the village of Strasburg. The Rebels were familiar with this position, having occupied it the month before. Early knew that Phil Sheridan would not be long in following his army. He also knew that Fisher’s Hill offered a formidable challenge to any attacker. Rising near Massanutten Mountain in the east, this natural defensive position extends westward for four miles to the base of Little North Mountain. Prying Early from this “Gibraltar of the Valley” would require a monumental effort from the Federals.

On the morning of September 20, the boys in blue marched in pursuit of the Confederates. Their spirits were buoyed from the recent victory on the fields east of Winchester. Reaching Strasburg that afternoon, the column came to a halt, the Confederates looking down on them from above the Valley floor.

Sheridan decided to reconnoiter Early’s position. Peering up at the enemy earthworks on the crest, he decided that “Fisher’s Hill was so strong that a direct assault would entail unnecessary destruction of life, and…be of doubtful result”. Little Phil elected to call a conference of war at his headquarters and discuss the situation with his subordinates. While Sheridan observed the Confederate lines, Brig. Gen. George Crook was conducting his own scouting mission along the Back Road near the Confederate left flank near Little North Mountain. Interestingly enough, Crook would come to a different conclusion than his superior.

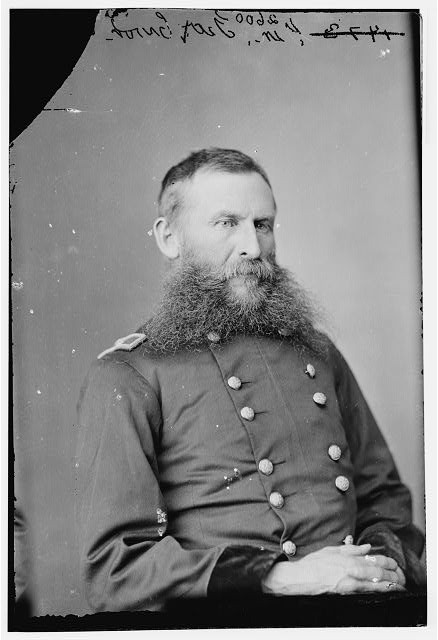

Crook was born outside of Dayton, Ohio on September 8, 1828. Graduating near the bottom of the West Point Class of 1853, Crook served in the 4th U.S. Infantry prior to the outbreak of the war. In the fall of 1861, he was appointed Colonel of the 36th Ohio infantry and served in western Virginia. Crook would command a brigade during the Antietam Campaign and lead his men in action at South Mountain. After the Battle of Stones River, he would be transferred to the Army of the Cumberland to serve in the Union cavalry. He would participate in the Tullahoma Campaign and fight at Chickamauga. With his service over in the West, Crook returned to western Virginia, where in August, 1864, Crook was appointed to command the Department of West Virginia. When the Middle Military Division was created with Phil Sheridan at its head, Crook’s Department fell under Sheridan’s command. Crook had known his new superiors since their West Point days, where they had been roommates.

Crook’s two divisions-known as the Army of West Virginia-were a nice complement to Little Phil’s army. As the name implied, the bulk of Crook’s men came from West Virginia, with other regiments hailing from Ohio, Pennsylvania and Massachusetts. These tough minded soldiers were proud to call themselves “Crook’s Buzzards” and had rendered valuable service to Sheridan during their attacks at Third Winchester. Unbeknownst to them on the evening of September 20, they would be called upon to play an important part in the upcoming operations.

Sheridan would meet with his subordinates in the yard of the Hupp House, just north of Strasburg. Present, along with their respective staffs were Crook, Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright, commanding the VI Corps and William Emory, commanding the XIX Corps. Crook also brought along one of his division commanders, Col. Rutherford B. Hayes.

The group quickly concluded that attacking the Rebels head on would be suicidal. Moving against the Confederate right, buttressed near the Shenandoah River also posed problems, as the Federals would come in view of the Confederate signal station atop Massanutten Mountain. Then it came time for Crook to present his idea. The enemy left was lightly defended; Early had posted some cavalry videttes along the Back Road. A flanking force could easily move along the base of Little North Mountain to a position astride the Rebel line, overwhelm the pickets and then strike Early’s left flank. Crook then asked Hayes to add his opinion as to the feasibility of such a maneuver. Somewhat skeptical, Sheridan finally relented and agreed to Crook’s and Hayes’ suggestion. Wright and Emory would support the assault by attacking the Confederates in their front, but only after Crook’s attack moved forward and if it showed signs of success.

The next day, the VI and XIX Corps marched out of Strasburg to take up a new position directly opposite Fisher’s Hill. This general movement was designed to induce Early into believing the Federals were indeed going to launch a frontal assault. As the Yankee infantrymen lumbered into position, “Crook’s Buzzards” waited impatiently under cover north of town near Cedar Creek. As day faded into night, Crook’s divisions moved to the north bank of the stream. Around 2 p.m. on September 22, the march toward Little North Mountain began.

Crook himself led the way. He would later write that he traversed “a succession of ravines, keeping my eyes on the signal station on top of the mountain so as to keep out of their sight, making the color bearers trail their flags so they could not be seen. As soon as I got under cover of the timber, I halted and brought up my rear division alongside of the first, and in this way marched the two by flank, so that when I faced them I would have two lines of battle parallel to each other…the slope of the mountain was one mass of rocks…covered with a small growth of timber, amounting to underbrush in places. Having reached the desired distance, I faced the command to the front, and then had two lines of battle, one in the rear of the other. I gave instructions not to yell until I gave the word”. The clock had reached 4 p.m. and Crook gave the order to go forward.

Down the slope of the mountain the Buzzards went, crashing into Early’s cavalry. The gray horsemen quickly collapsed, and the Yankees continued onward, toward the infantry lines. Crook wrote that the “batteries from the bluffs toward the center of the enemy’s lines, together with some troops near there, were making the ground hot for us. Some of my men were disposed to linger in the edge of the woods. I gathered my arms full of rocks and made it so uncomfortable for this rear that they tarried no longer”.

Crook’s divisions struck Early’s left, defended by Maj. Gen. Stephen Ramseur. The North Carolinian attempted to shift some of his brigades to deal with the threat, only to find that Wright’s divisions were storming his immediate front. Caught in a vise, the Rebel line atop Fisher’s Hill began to collapse. The added weight of Emory’s assault on the right made it crumble and Early’s infantrymen scurried for the rear. While a few units managed to make a brief stand, the Confederates continued their retreat along the Valley Pike. Darkness finally brought an end to the pursuit. For the second time in three days, Phil Sheridan’s army had dealt another defeat to Jubal Early.

Credit, however, for the victory would remain a question for years to come. In his Official Report of the campaign, Sheridan claimed that it was his idea to launch the flank attack. Writing his memoirs later in life, Sheridan stated that he “resolved on the night of the 20th to use…a turning column against his [Early’s] left…to this end I resolved to move Crook…over to the eastern face of Little North Mountain”. These musings on the part of Sheridan were a downright insult to not only a personal friend, but to a man who had served him faithfully through the fighting in the Shenandoah Valley. It is quite possible that Sheridan made these statements to further his own career.

Fortunately, some of Crook’s subordinates knew better. Hayes, who was present at the council of war when the assault was planned wrote “at Fisher’s Hill the turning of the Rebel left was planned and executed by Crook against the opinions of the other Corps generals”. Crook’s Chief of Artillery, Henry DuPont corroborated Hayes’ account “it was fully understood by everyone…that Crook had suggested this movement and asked permission to move his infantry…so as to turn the enemy’s left”.

Ironically, Crook is better known today for his post-war exploits than for his actions during the Civil War. He would command a column during the 1876 Sioux War-a campaign that saw the defeat of George Custer at the Little Bighorn-and fight against the great Apache war chief Geronimo in Arizona. His last post was commanding the Military Division of the Missouri. Crook died on March 21, 1890 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Interesting post; thank you.

I have a soft spot for George Crook. He commanded a division of cavalry ably under Rosecrans. He says in his memoirs that he regretted his transfer back to West Virginia, because he thought he had a good chance of being promoted to command all the Army of the Cumberland’s cavalry once David Sloane Stanley was transferred to an infantry command. I think he would have done a better job for Sherman than Elliott or Kilpatrick managed.

Very good article.

The more I read about Phil Sheridan, the more he seems like a nasty piece of work.

Yes, Sheridan could be egotistical and greedy. Yes, he tried to give the impression, both in his official report and his memoirs, that the flank attacks at Third Winchester and Fisher’s Hill were solely his ideas. Notwithstanding this, he gave George Crook his due.

On 23 September 1864, he recommended Crook for promotion full major general of volunteers: “His good conduct, and the good conduct of his command, turned the tide of battle to our favor at both Winchester and Fisher’s Hill.” (Crook was promoted as soon as a vacancy was available.)

On 2 May 1866, Sheridan recommended Crook for a brevet major generalcy in the Regular Army for his actions at Winchester & Fisher’s Hill: “His skill and courage in these two battles was called upon at the decisive periods of the engagements and to him may be given the credit of the first decisive success and entitles this brevet to date from the battle of Opequon, September 19, 1864” “His service in the East, in West Virginia, then in the West, then in the East, give him a better record than many of those recommended by the Army Board, of which I was an absent member .”

In August 1866, Sheridan recommended his friend for a full colonelcy and regimental command in the new Regular Army: “My Dear Crook: I wrote to General Grant this morning as soon as your letter was received, asking him to give you a regiment if possible. I have previously recommended you. I hope this last letter will make the appointment certain. I have always thought you were entitled to one of the regiments… Believe me your sincere friend, P. H. Sheridan…”