Looking Back to Cowpens: William J. Hardee and the Battle of Averasboro

After abandoning Fayetteville, North Carolina to Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s army group, Lieutenant General William J. Hardee withdrew his corps north of the city. Hardee had ordered the Clarendon Bridge over the Cape Fear River destroyed, removing the possibility of a vigorous pursuit by the Federals. The situation for the Confederates, however, remained dire. Hardee’s immediate superior, Gen. Joseph Johnston, was in the process of assembling a makeshift army to delay Sherman’s advance. By the middle of March, the forces that Johnston hoped to consolidate were still scattered throughout the state. More time would be needed for the Confederates to rendezvous. Since Hardee’s corps was naturally positioned to contest the enemy as they left Fayetteville, it would fall to him to engage Sherman once he resumed his march. The veteran officer would prove to be more than equal to the task.

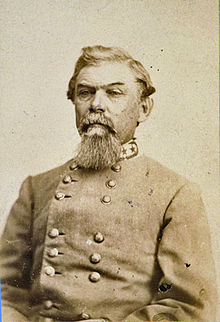

A native of Georgia, Hardee was a West Point graduate who served in the War with Mexico. Known as “Old Reliable”, Hardee had forged this sobriquet at Shiloh, Murfreesboro and at the gates of Atlanta. Leaving the Army of Tennessee after Jonesboro, Hardee transferred to command the Department of Georgia, South Carolina and Florida. Fayetteville was yet another major city that Hardee was forced to abandon in the face of Sherman’s juggernaut. First came Savannah and then Charleston. This fact may have eaten at the quiet professional. Taking up a position between the Cape Fear and the Black Rivers, Hardee would have an opportunity to exact payback to the Yankees. Rather than looking into his own past for inspiration, Hardee may very well have looked to a battle in America’s past that fit his plan for delaying Sherman.

Hardee possessed an acute military acumen. In the early 1850s, then Secretary of War Jefferson Davis had commissioned Hardee to compose a manual for drill. The work, Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics, would become popular with officers on both sides of the Civil War. A student of American military history, quite possibly could have formulated his battle plan on that which Daniel Morgan used to defeat Banastre Tarleton at the Battle of Cowpens during the American Revolution. During the engagement, Morgan utilized what is known as a defense in depth to defeat a counterpart that both exceeded his own force in numbers and experience

A defense in depth dictates that defending troops form parallel lines, usually several hundred yards behind one another. The first line will fight as long as possible and then withdraw to the next line behind them. This position, with added numbers then engaged the enemy. Once it became untenable, these troops would fall back to the next position, which is made up of veteran soldiers. If the first lines are able to hold off the attack long enough, by the time the last line is reached, fatigue and exhaustion will have set in and they are vulnerable to a counterattack by the combat hardened veterans.

On March 16, 1865, 150 years ago today, what became known as the Battle of Averasboro was joined between Hardee’s corps and elements from Maj. Gen. Henry Slocum’s Army of Georgia. Exactly as the tactic called for, Hardee had arranged his men into three parallel lines. Col. Alfred Rhett’s brigade, under the direction of Col William Butler, manned the first position. A couple hundred lines behind Butler was Col. Stephen Elliot’s men. Hardee used Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws to backstop the position.

The engagement began to take shape according to plan. As Slocum’s infantry came on, Butler’s men put up a stiff fight, forcing the Union commander to bring and deploy the XX Corps divisions of Brig. Gens. Nathaniel Jackson and William Ward. Finally, Col. Henry Case’s brigade pried Butler from his position by turning his left flank and the Confederates withdrew to Elliot’s line. Elliot’s men were able to hold until they were overwhelmed by the oncoming blue divisions. Falling back to McLaws’ position, Hardee reinforced this line by deploying Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler’s cavalry to McLaws’ right flank. This decision proved fortuitous, as the Federals attempted to replicate Case’s earlier attack. An advance by Col. William Vandever’s newly arrived brigade from Brig. Gen. James Morgan’s XIV Corps division was blocked by Wheeler’s troopers. Darkness and heavy rains finally brought an end to the fighting.

That night, Hardee decided to abandon his position. The fight he had orchestrated had served its purpose. It had bought Johnston a precious day to consolidate his forces. Three days after Averasboro, Johnston struck the Federals at Bentonville. The determined stand by “Old Reliable” had made it possible. Similar to John Buford’s covering force action northwest of Gettysburg on July 1, 1863, Hardee’s battle was a tactical wonder.

Following the end of the war, Hardee moved to Selma, Alabama and the former soldier became a planter. He passed away on November 6, 1873 and is buried there. Averasboro stands today perhaps as his greatest military achievement.

So well written I could vizualize Hardee’s formation and the play-out of his tactic. Still in the big picture of the war Sherman and his men never lost momentum or did Appomattox lead the opposition to decide further fighting was useless and would only cause more death?

Thank you for the kind words, they are much appreciated. Sherman, indeed, never lost momentum. He had planned to strike north from Goldsboro, North Carolina to cut off the Southside Railroad leading into Petersburg. This never materialized as Petersburg fell before Sherman could fully implement his plan. Instead, he decided to march west in an effort to seize Raleigh and keep Lee and Johnston from uniting. Sherman had only made it as far as Smithfield when he learned of Lee’s surrender at Appomattox.

Lee’s surrender was a result of him being surrounded in the Appomattox River Valley and thus he decided that any further effusion of blood would be useless. Jefferson Davis, however, viewed the surrender as the loss of just one of his armies, but would ultimately be overruled by his military officers as far as opening communication with Sherman on the discussion of surrender.

Dan: Great article as usual. But I just have to ask: How could Hardee be “in the wake of the advance”? Was he behind it or in front of it?