Appomattox and Bennett Place: A Remarkable Contrast

I had the honor and privilege of attending and participating in a portion of the weeklong commemoration sof the surrenders at Bennett Place on April 18, 2015, the 150th anniversary of the signing of the initial peace treaty by Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman and Gen. Joseph E. Johnston. Sadly, I won’t be there for the commemoration of the final surrender or to see the ceremonial stacking of the guns. The weather did not entirely cooperate. A heavy thunderstorm rolled through that inhibited attendance. It’s fair to say that several hundred visitors attended, perhaps as many as a thousand or so over the course of the day, but I cannot give a precise number. I have no doubt that the final surrender commemoration will draw substantially more attendees, and I hope that it does do so.

I was not at the commemoration of the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox, but in speaking with Ranger Bert Dunkerly and others who attended the events, I understand that approximately 30,000 people attended the commemoration. The stark contrast in the attendance figures reflects the differences between the two sites and the way that these important events are remembered today.

The entire village of Appomattox Court House was purchased by the War Department and was turned into a shrine. It’s now part of the National Park Service, with many of the buildings–including Wilmer McLean’s handsome home–having been reconstructed as replicas of the original structures on their original sites. The McLean house is furnished with some of the original furnishings or with exact reproductions. The Appomattox Court House National Park consists of 1800 acres and includes 27 original structures. There are numerous monuments, and the small battlefield area–the fight was brief and aborted when Lee realized that Union infantry had arrived and that his plight was hopeless–is well interpreted. There’s even a small Confederate military cemetery on site. The entire surrender field is also fully preserved. There is a large Eastern National Park & Monument Association bookstore with an excellent selection, and a visitor center with a nice museum.

In addition, the site of the fight at Appomattox Station, which occurred on April 8, 1865, the day before Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia, has recently been acquired by the Civil War Trust, and is in the process of being interpreted and made available to the visiting public. Further, the Museum of the Confederacy has constructed and opened a branch museum site close to the national park boundary and near the Appomattox Station battle site.

In short, Appomattox is a place well worth visiting. One could easily spend a couple of days seeing everything that there is to see, all of which presented beautifully.

I’ve already written about the surrenders at Bennett Place here—see Events Larger than One Person—and I need not repeat those posts here. There is no question that Robert E. Lee was a great man. It took a great man to swallow his pride—“I would rather die a thousand deaths,” to use his words—and surrender his army for the betterment of the entire country the way he did. There is a reason why Lee is as revered of a figure as he is to this day.

But the comparative greatness of Joseph E. Johnston is all too often overlooked. Let’s remember that Confederate President Jefferson Davis fired Johnston during the Atlanta Campaign and that he had gone off into retirement afterward. At Lee’s request, Johnston voluntarily returned to duty to attempt to help to save the cause. He had the difficult task of reassembling and refitting the remnants of the Army of Tennessee and also gathering the remaining Confederate forces in the Carolinas and Georgia to try to resist the advance of Sherman’s army. It was a long shot at best.

Unlike Lee, Johnston inflicted a severe blow on Sherman at Bentonville, and then escaped with his army intact and able to fight another day. Unlike Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, Johnston’s army was never surrounded or brought to bay by Sherman. Instead, after the surrender of Lee’s army, Johnston recognized that the cause had been lost and that there was no reason at all to continue the shedding of blood for no good reason. Johnston recognized that the time had come to bring an end to the war, even though doing so meant that he would disobey the direct orders of Jefferson Davis. It took a man of real depth and character to do what Johnston did, and he has never gotten the credit for what he did that he deserved.

It’s important to remember that after Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox, there were still three major Confederate armies in the field: Johnston’s army in North Carolina, Richard H. Taylor’s army in Alabama, and Edmund Kirby-Smith’s army in the Trans-Mississippi. Contrary to popular belief, Lee’s surrender did NOT end the Civil War. Johnston had a nearly insurmountable lead over Sherman’s army, and Sherman would have been hard-pressed to bring Johnston to bay had Johnston not decided that further bloodshed would have been completely useless. There were approximately 90,000 Confederate soldiers still under arms after Lee surrendered at Appomattox.

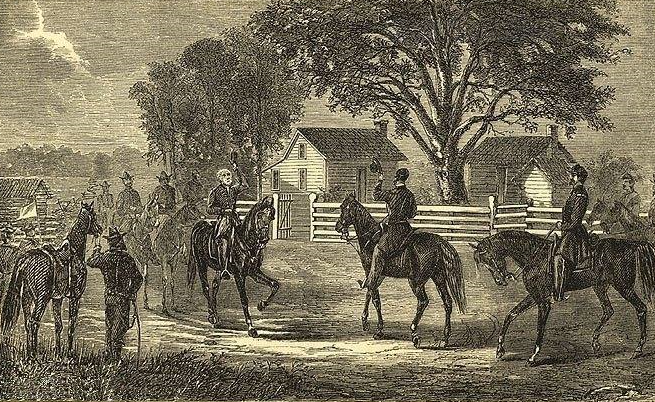

Disobeying Davis’ direct orders, Johnston asked for a truce, and arrangements were made for Johnston to meet Sherman at James and Nancy Bennett’s farm, about four miles from Durham, NC. There, on April 17, the two commanders met and negotiated not just the surrender of Johnston’s army, but peace. They negotiated an end to hostilities as well as the surrender of Johnston’s army. Sherman gave Johnston extremely generous terms, and they signed an agreement on April 18, subject to government approval. Although Jefferson Davis readily approved these liberal terms, an angry Federal government, still stinging from the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, rejected them. Grant then ordered Sherman to re-negotiate the terms with Johnston to match those given to Lee at Appomattox.

Davis, opposed the surrender of Johnston’s command under the terms given to Lee, ordered Johnston to disband the infantry and escape with the large force of cavalry attached to Johnston’s army. To his undying credit, Johnston disobeyed those orders, met Sherman again on April 26, and surrendered the nearly 90,000 Confederate troops still under arms on the same terms given to Lee’s army at Appomattox. The troops included men in the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida. Only after Johnston surrendered did Taylor and Kirby Smith finally surrender, too. The last Confederate soldiers did not lay down their arms for a couple of months.

In many ways, what happened at Bennett Place is more remarkable, and more important, than what happened at Appomattox. However, the Bennett Place episode has long lingered in the shadow of the events at Appomattox, which is very unfortunate.

One explanation for the fact that Bennett Place has long been overshadowed by Appomattox is the fact that Abraham Lincoln was assassinated a few days after Appomattox and before Bennett Place. The President’s death, the hunt for the assassins, their trials and executions, and the slain president’s funeral occupied the attention of the public for months afterward. Harper’s Weekly did not even mention Johnston’s surrender to Sherman until May 27, devoting four paragraphs to the story, which shared space with an article titled “Paris Fashions for May” on the sixth page.

The Bennett Place surrender site is a North Carolina state park that occupies about 39 acres, counting a recent acquisition of another two acres. Unfortunately, nobody thought to preserve the rest of the 200-acre Bennett farm decades ago when something could have been done about it, and the site is now surrounded by extensive residential and commercial development near the Duke University campus, which limits the possibility of expansion. The park opened in 1962.

The park features an exact reproduction of the Bennett farmhouse and one of its outbuildings that stand on the foundations of the original structures. A small portion of the original dirt road still runs by the house, and is the same dirt road that carried Sherman and Johnston to their epic meetings. A handsome and very moving Unity Monument commemorating the reuniting of the country was installed on the grounds. There is a bandstand, and a commemorative bench.

The visitor center features a full reference library with more than 2,500 volumes and other research materials for those wanting to investigate the events that occurred at Bennett Place. The visitor center has a full gift shop with a nice selection of books, toys, and other souvenirs. It also features a beautiful little museum with a brand-new set of displays that was dedicated on April 17, 2015, and also has a small theater that tells the story of the events that occurred at Bennett Place. Finally, there are a number of picnic tables and nature trails for those who want to explore the site.

The contrasts between the two sites are remarkable. The National Park Service has devoted very substantial resources to telling the story of what happened at Appomattox and had the foresight to preserve the entire site, while it completely overlooked and neglected Bennett Place. The State of North Carolina has done a great job with what it has there, but unfortunately, the hands of time cannot be wound back, the rest of the Bennett farm cannot be saved, and the extensive development that landlocks Bennett Place cannot be undone. John Guss, the site director, and his excellent staff do a great job with what they have. But the contrast between Appomattox and Bennett Place remains stark.

Traditionally, historians have given much more focus to Appomattox than they have to the events that occurred at Bennett Place. There have been many books written about the surrender at Appomattox, including one in the Emerging Civil War series sponsored by this blog. There has only been one deeply researched scholarly study of the events that took place in North Carolina: Mark L. Bradley’s excellent This Astounding Close: The Road to Bennett Placehttp://www.amazon.com/This-Astounding-Close-Bennett-Place/dp/0807857017/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1430135448&sr=1-1&keywords=this+astounding+close+the+road+to+bennett+place published by the University of North Carolina Press in 2000. Even in terms of scholarly historical treatment, Bennett Place lingers in the shadows of the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox.

Recently, Savas Beatie published Bert Dunkerly’s work in the Emerging Civil War Series To the Bitter End: Appomattox, Bennett Place and the Surrenders of the Confederacy. This book not only examines the surrenders of Lee and Johnston’s but the capitulation of the other Confederate armies.

The contrasts are stark. But both sites are well worth visiting, and are well worth studying. To truly understand the story of the end of the Civil War in 1865, one must study both surrenders, because focusing only on the events at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865 excludes the extraordinary events that occurred in Durham, North Carolina on April 17, 18 and 26, 1865, where the Civil War really ended, thanks to the greatness of William T. Sherman and Joseph E. Johnston, who were determined to begin the process of healing the wounds inflicted by four years of brutal war.

Ha! You can practically see daggers shooting out of Kilpatrick’s and Hampton’s eyes in that modern painting.

“Disobeying Davis’ direct orders, Johnston asked for a truce…”

“…even though doing so meant that he would disobey the direct orders of Jefferson Davis.”

“… Davis, opposed the surrender of Johnston’s command under the terms given to Lee, ordered Johnston to disband the infantry and escape with the large force of cavalry attached to Johnston’s army. To his undying credit, Johnston disobeyed those orders,”

Like he and Davis were on the best of terms. It probably motivated him that Jeff Davis didn’t want to give up.