Longstreet Goes West, part four: Discord

In the immediate aftermath of Chickamauga, Bragg and his generals were all gripped by a measure of collective uncertainty. Early on, it seemed as if Rosecrans might just abandon Chattanooga, falling back to his railhead at Stevenson, Alabama, on the north bank of the Tennessee River. As the days passed and it became apparent that the Federals were in fact going to remain, entrenching furiously; uncertainty gave way to frustration.

In one aspect, the reaction within each army – both the victors and the vanquished – was remarkably similar: a purge ensued.

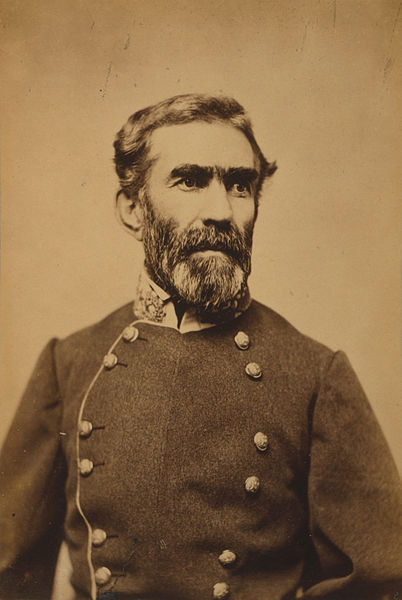

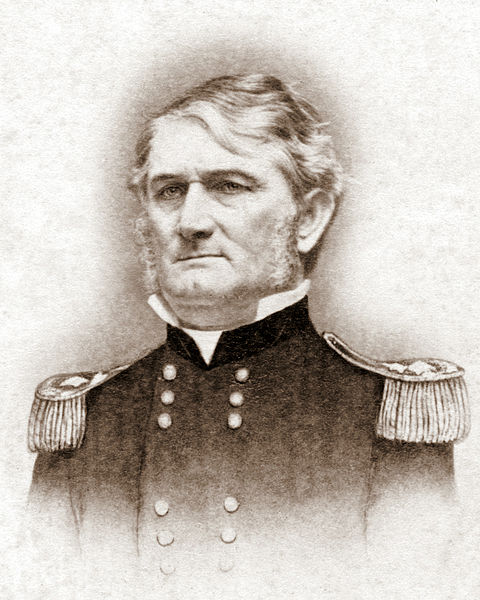

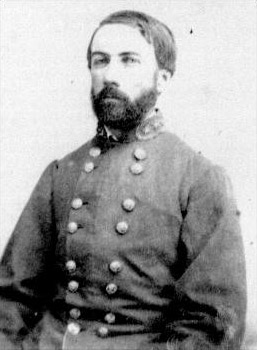

The defeated Yankees shed one divisional commander, two corps commanders, and, ultimately, Rosecrans himself. On the southern side, Bragg retained command, but also rid himself of a divisional commander (Thomas C. Hindman) as well as two corps commanders, Leonidas Polk and (eventually) Daniel Harvey Hill. He also reshuffled his table of organization, hoping to minimize the effectiveness of his remaining critics. Bragg created such havoc within his own army that no less a figure than President Jefferson Davis himself would have to travel west in order to try and resolve the crisis.

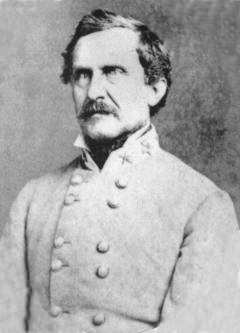

There has been a tendency among some historians to view the post-Chickamauga discord within the Army of Tennessee as primarily a power struggle between James Longstreet and Braxton Bragg – fueled, in part, by Longstreet’s ambition.

I view this as a mistaken interpretation.

It was really a power struggle between Bragg and his principal subordinate, Episcopal Bishop & Lieutenant General Leonidas Polk. This struggle began in the spring of 1862, and blew up into the army’s first command crisis the following year, in the spring of 1863, the result of fallout from both the Perryville and the Murfreesboro campaigns. Much to Bragg’s growing frustration, Polk, though popular among the men, proved consistently incapable as a commander. The Bishop paid very little attention to military discipline, relying instead on the fact that he was a West Point classmate and close personal friend of Jefferson Davis to paper over any missteps.

Bragg was very nearly relieved of command in March of 1863, saved only by Joseph E. Johnston’s own reluctance to assume that position in his stead and thus appear to be scheming against Bragg for his own gain. Davis’s decision to retain Bragg while at the same time sustaining Polk, however, resolved none of the army’s core issues.

This time Bragg intended the showdown to be final. As he told his wife, Elise: “Again I have to complain of Genl Polk for not obeying my orders, and I am resolved to bring the matter to an issue this time. One of us must stand or fall.”

On September 22, Bragg dictated a tersely worded formal note to the Bishop: “GENERAL: The General commanding desires that you will make as early as practicable a report explanatory of your failure to attack the enemy at daylight on Sunday last in obedience to orders.”

Polk, who fully understood what was coming, immediately began marshalling his own resources. On the 23rd, he paid visits to D. H. Hill and James Longstreet, soliciting their support. Polk intended to write to the President, and wanted to name Hill as a supporter. Polk also wanted Longstreet to write a letter to Davis, an independent corroboration of his criticism. Hill, increasingly certain he was about to be “scapegoated,” agreed to let Polk list him as in agreement. Longstreet chose not to write Davis directly, but on September 26 penned a lengthy letter to Confederate Secretary of War James G. Seddon – a mere fig leaf, for Longstreet had to know Davis would see any such letter within minutes of it hitting the secretary’s desk.

Though he was unaware of Polk’s plot, Bragg struck first. On September 25, in a private letter to President Davis, Bragg detailed the problem officers as he saw them:

In McLemore’s Cove, wrote Bragg, Hill and Hindman “fail[ed] to execute” their orders. On September 20, the fault lay with Polk.

“Genl Polk . . . is luxurious in his habits, rises late, moves slowly, and always conceives his own plans the best. He has proved an injury to us on every field where I have been associated with him.”

And Hill?

“Genl Hill is despondent, dull, slow, and tho gallant personally, is always in a state of apprehension, and upon the most flimsy pretext makes each report of the enemy about him as to keep up constant apprehension, and require constant reinforcements. His open and constant croaking would demoralize any command in the world. He does not hesitate at all times and in all places to declare our cause lost.”

Bragg reserved praise for four officers; Patrick Cleburne, the badly wounded John B. Hood, as well as (ironically) James Longstreet and Simon B. Buckner.

Polk’s letter to Davis warning the chief executive of Bragg’s “incapacitation,” suggesting he was incapable of leading, and asked Davis to “send Lee or some other” to take Bragg’s place.

Longstreet’s letter to Seddon was scathing. After setting forth a litany of detailed complaints, Longstreet closed with a sweeping indictment of Braxton Bragg. The head of the Army of Tennessee, he observed, “has done but one thing he ought to have done since I joined this army. That was to order the attack upon the 20th. All other things that he has done, he ought not to have done.”

Polk and Longstreet both also wrote separate letters to Robert E. Lee, appealing for that general to come west and replace Bragg. Lee declined.

On September 28, having launched his covert salvo against Bragg, Polk replied to Bragg’s demanded explanation. Unhesitatingly, the duplicitous Bishop threw his ally, D. H. Hill, under the proverbial omnibus. In a detailed response, Polk listed multiple points where Hill was to blame for the delayed attack. Bragg remained unswayed. On September 29, Bragg suspended both Polk and Hindman (who was already absent, recovering from a neck wound) and Polk departed for Atlanta. A court-martial now seemed in the offing.

Longstreet and Hill remained with the army, though when Hill saw Polk’s explanation of the September 20 failure he was shocked and dismayed to discover that he was the main target of Polk’s blame-finding. Polk’s departure, however, resolved nothing. Bragg was determined to squash any and all opposition, which, if anything, only hardened the dissension among Bragg’s remaining senior officers.

Chief of Staff William Mackall foresaw what was to come. Also on September 29, in a private letter to Joseph E. Johnston, Mackall predicted that “if Bragg carries out his projects, there will be great dissatisfaction. I have told him so, but he is hard to persuade when in prosperity, and I do not think my warning will be heeded until too late.”

Bragg and Davis exchanged lengthy telegrams through the first couple of days in October, with Davis pointing out that Bragg had exceeded his authority by suspending Polk (the army commander could arrest and prefer chargers, but not unilaterally relieve officers – that was the President’s prerogative.) Bragg offered up the idea of swapping Polk for Hardee, then in Alabama; that idea would come back into play later. Davis, however, was also concerned that Bragg had suspended two officers, but left Hill alone; this seemed like selective judgement to the President.

From this turmoil stemmed the infamous “Petition.” This extraordinary document was prepared as an indictment of Bragg’s performance. It informed President Davis that the Army of Tennessee was in a state of “complete paralysis,” which was why Rosecrans was able to retreat safely into Chattanooga, that the Confederates needed reinforcements, and, finally, requested that Bragg be relieved of command for the “sufficient reason” that “the condition of his health unfits him for the command of an army in the field.”

Who wrote it? In 1890 William Polk, Leonidas’s son, provided a copy for the official records, which, he wrote, was “supposed to have been written by [Simon B.] Buckner.” Another suggested author was Daniel Harvey Hill, who denied having penned it, though he did later say that he “signed it willingly.” In his memoir, written eight years after Hill’s death, Longstreet stated that Hill told him that he was indeed the author. Whatever the origin, Hill certainly kept it at his headquarters, where a number of officers eventually signed it: Longstreet and Hill, as the army’s two ranking corps commanders; divisional commanders Bushrod R. Johnson, William Preston, and Patrick R. Cleburne, and six brigade commanders. Polk was of course not present, and John C. Breckinridge declined to sign, arguing that his well-known pre-existing troubles with Bragg would only prejudice the document.

The petition’s existance was an open secret. Trouble was in the wind, and the whole army was now talking about discord in the senior ranks. On October 5, Brig. Gen. James R. Chesnut – Davis’s personal aide and currently acting as envoy in the west, telegraphed the alarm from Atlanta: “Your immediate presence in this army is urgently demanded.”

The showdown was at hand.

Ol’ Braxton didn’t age well, did he?

He has always looked – to me, anyway – like I expected him to, based on his reputation. Which doesn’t seem to bode well for him.

Dave Powell writes in the first sentence of this piece: “In the immediate aftermath of Chickamauga Bragg and his generals were all gripped by a measure of collective uncertainty.” Very true. Another glaring example of the dysfunction that existed in the leadership of this army. That is a violation of one of the key facets of Operational Art, which is “Timing and Tempo,” which means continuing to harness initiative as not to allow your opponent to mount a successful defense.

Now, Longstreet was consulted by Bragg on the morning of the 21st what he thought they should do? Longstreet stated this army should be moving already to press the initiative. He got it. Between the 21st and maybe the 23rd Bragg still had an opportunity to attack. On these days the Union army was atop Missionary Ridge and had an open flank on their left, which could have been attacked before they pulled back into Chattanooga to begin defensive position improvement there. This uncertainty squandered that opportunity. After that, the only other option for Bragg was to go after Bridgeport/Stevenson and shut down the entry point for reinforcements and supplies.