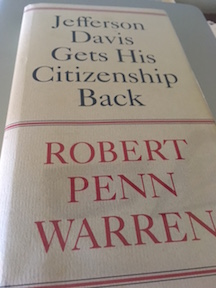

Robert Penn Warren’s Reflections on Jefferson Davis’s Citizenship

As I mentioned in a post a couple weeks ago, I had the opportunity recently to pick up Robert Penn Warren’s short 1980 book Jefferson Davis Gets His Citizenship Back. It’s beautifully written, and Warren’s ambivalence about his native South imbues the piece with thoughtful reflection.

As I mentioned in a post a couple weeks ago, I had the opportunity recently to pick up Robert Penn Warren’s short 1980 book Jefferson Davis Gets His Citizenship Back. It’s beautifully written, and Warren’s ambivalence about his native South imbues the piece with thoughtful reflection.

Warren originally wrote the piece in 1979 for The New Yorker after special Act of Congress restored Davis’s citizenship, an act signed into law by President Jimmy Carter—like Warren and Davis, a Southerner.

Warren’s portrait of Davis, whom he considers too old-fashioned for the maelstrom he found himself thrust into, is quite sympathetic, and it helped me understand Davis a bit better. Warren was less fond of his and Davis’s fellow native son, Abraham Lincoln. Sherman and Grant, Warren contends, were “modern men,” although Warren wrote at a time when Grant’s reputation was in the pits, and that comes through in Warren’s own interpretation. Only through his end-of-life writing project, his memoirs, did Grant seem to redeem himself (an unsurprising interpretation coming from Warren, himself a writer.)

One of the things I do when I read a book is mark the pages where I find good writing or thought-provoking ideas. Typically, I fold over the corners—which mortifies book-collector friends—but I don’t make any marks on the pages themselves. That way, down the road when I revisit the book, I have to reread the page in order to find the passage that originally intrigued me. This has two advantages: First, it might allow fresh passages to jump out at me that didn’t the first time through; second, it’s a chance to test whether the original passages still resonate with me.

With Jefferson Davis Gets His Citizenship Back, I didn’t fold page corners. Instead, I tucked slips of paper in as bookmarks. Rather than writing a full review of the book, I thought I’d share a couple of the passages that struck me as most thought-provoking. I’m still mulling them over, so perhaps you’d like the opportunity to mull them over, too.

- On Davis’s (and Lee’s) insistence on loyalty to their home states over the national government: “How odd it all seems now—when the sky hums with traffic, and eight-lane highways stinking of high-test rip across hypothetical state lines, and half the citizens don’t know or care where they were born just so they can get somewhere fast.” (49)

- On the waning days of the Confederacy: “Merely some notion of Southern identity remained, however hazy or befuddled; it was not until after Appomattox that the conception of Southern identity truly bloomed—a mystical conception, vague but bright, floating high beyond the criticism of brutal circumstances.” (59)

- On the question of “What If?”: “Wars tend to be iffy. And there were undoubtedly ifs in the Civil War—historians are still engaged with them.” (68)

- A quote Warren passed along by Gerrit Smith, one of the so-called “Secret Six” who financed John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry: “I have ever held that a sufficient reason why we should not punish the conquered South is that the North was quite as responsible as the South for the chief cause of the war . . . the mercenary North coolly reckoned the political, commercial, and ecclesiastical profits of slavery, and held to it.” (84)

- On Jefferson Davis getting his citizenship back: “Davis died without rancor, and wishing us all well. But if he were not now defenseless in death, he would no doubt reject the citizenship we so charitably thrust upon him. In life, in his old-fashioned way, he would accept no pardon, for pardon could be construed to imply wrongdoing, and wrongdoing was what, in honor and principle, he denied.” (112)

I’d be interested to hear what you think about any of these points….

Thought provoking. I think the final conclusion about Davis is correct. Most of us in his position would reject any idea or admit to any wrong.

Interesting, and book I have never read. He is a fine writer, but I think goes over the top in an effort to be poetic and flowery, which in turn undercuts the factual force or truthfulness or accuracy of what he is trying to convey.

(Passage 49)

“Highways stinking of high-test…” Ha. I wonder how many know what that even means today? I do because I am old.

Playing attorney a bit….state lines are not hypothetical. If so, than we elect hypothetical governors, hypothetical legislatures, pay hypothetical taxes, etc. “Invisible” might have been a better word.

Half the people don’t know where they were born? Or care where? Odd. And surely false.

(Passage 59)

I don’t think reading the letters or diaries or newspaper accounts from 1860 (or arguably, before) through 1865) one can state that the notion of Southern identity was not firmly planted or as separate and distinct as the notion of being a frontiersman or city dweller. I am not a Southerner, but I don’t buy this at all. Now perhaps he means Lost Cause? If that is the case it is sloppy writing.

(Passage 68)

Agreed.

(Passage 84). Some reflected responsibility, I think is correct. Quite as responsible? Seems like overkill to make a point.

(Passage 112)

His best point, and he is surely correct.

Interesting exercise, Chris, and one I am sure others will take umbrage with. Such is the fun of the genre.

Here’s the full passage from pg. 59 for context: “So, with states’ rights obviously bringing on disaster, King Cotton dethroned, and blacks wearing Confederate gray, little was left of the ideas that had made the Confederacy—only secession, in fact. But with the armies of Sherman and Grant closing in and defeatism stalking the land, what would become of that notion—a notion that for many eminent Southerners, including Davis and Lee, had been from the first dubious or rueful? Merely some notion of Southern identity remained, however hazy or fuddled; it was not until after Appomattox that the conception of Southern identity truly bloomed—a mystical conception, vague but bright, floating high beyond the criticism of brutal circumstances.”

I’ve pondered “hypothetical” versus “invisible” versus “arbitrary.” I think he does mean hypothetical in the context in which he’s using it because he’s talking more about the notion of being “American” than being from a state, and so the state lines seem less important and less relevant. They’re there, but do they really matter? His argument was that, in 1979, no, they didn’t. What mattered was freedom and speed of movement.

Like you, I don’t agree with his “don’t care” comment.

Interesting Chris. Thanks for sharing.

I’ve never read Warren’s book and appreciate the report. I think the idea that I find most intriguing is what Warren identifies as the “vague” notion of Southern identity pre-Appomattox. That certainly fits with the home front accounts I have read from that time which mostly adhere to a more state-centric outlook and makes me wonder when and how the shift occurred. I wonder if the engine of change was the return of Confederate veterans to their homes post-Appomattox, bringing with them the commonality of having served a cause that transcended home-state distinctions and divisions.

I have read the book and enjoyed it; Davis remains an interesting American character .