Book Review: A House Built by Slaves

A House Built by Slaves offers a portrait of Abraham Lincoln, as seen through the eyes – the usually-but-not-uniformly-sympathetic eyes – of black visitors to the White House. The narrative also combines accounts of these visits with accounts of the background circumstances which prompted the visits.

A House Built by Slaves offers a portrait of Abraham Lincoln, as seen through the eyes – the usually-but-not-uniformly-sympathetic eyes – of black visitors to the White House. The narrative also combines accounts of these visits with accounts of the background circumstances which prompted the visits.

The book comes out at a time of debate about whether Lincoln was a racist. The short answer is “yes, but as the war went on he got a lot better.”

But be that as it may, many people today are genuinely interested in the question of Lincoln’s racism. Professor Jonathan White is largely on Lincoln’s side, emphasizing Lincoln’s fellow-feeling with those held in bondage, and his willingness to strike at slavery when political or military needs aligned with his own antislavery values.

The book also shows Lincoln evolution from a colonizationist – who wanted to free the slaves and then send them outside the country- into someone willing to have blacks and whites live together in the United States, on terms seemingly evolving toward equality.

Professor White, when confronting one of Lincoln’s racist prewar public statements, calls Lincoln “a man of his times.” Lincoln was also a man for his times, and as circumstances evolved, he was affected by that evolution and sometimes gave it a push, all in the direction of more freedom and equality for blacks. Though this was not always done as swiftly as black leaders would wish.

Professor White’s narrative shows that Lincoln saw no intrinsic need to put his personal antislavery principles into politics. I would suggest that Lincoln only mixed his antislavery views with his antebellum politics when he came to believe that an organized Slave Power was scheming to extend American slavery’s reach into new lands, like Mexico and Kansas. Unlike abolitionists, in short, Lincoln only took on slavery when he thought the Slave Power had introduced the question into national politics, to the detriment of the free states.

Lincoln went into the Civil War at first as a “mere” Unionist – forcing the country back together, not waging a war of slave-liberation. He even supporting sending back fugitive slaves under the fugitives-from service clause of the Constitution. If the war had ended promptly with an early Northern victory, Lincoln might not have evolved beyond this stance – keep the South in the Union, keep the slaves in the South, keep slavery from spreading to new areas.

But – spoiler alert – the war turned out to be prolonged, and the more prolonged it got, the more Lincoln was willing to free slaves where slavery actually existed. He hoped this could hasten the aid of the war and rid the country of an evil institution which had become an incubus and a threat to national unity.

When Lincoln began receiving prominent black people in the White House, it was in the context of this evolving stance on slavery and race in connection with the military and political situation.

We come to a White House meeting which Professor White calls one of Lincoln’s most “regrettable” moments: the lecture he gave to several prominent black figures on August 14, 1862, about the alleged need for blacks to emigrate out of the United States and enjoy whatever freedom they gained…elsewhere. “Without your race among us,” said Lincoln, “there would be no war.” Unlike other political meetings with black visitors, which were generally cordial and informal, this meeting came complete with a secretary to note down Lincoln’s remarks for publication in the newspapers.

The Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation was coming up, and so were the 1862 midterm elections. Lincoln was aware that racist Northern white voters would be worried about their communities getting flooded with slaves who had been freed by the Proclamation. So as Professor White suggests, Lincoln made his remarks with an eye to these white voters. And from Lincoln’s own point of view at the time, freedom did not necessarily mean equality, at least not equality within America.

But as Lincoln came to accept the recruitment of freed slaves, and black people generally, into the ranks of Union private soldiers, his enthusiasm for emigration may have faded as he realized that those who were good enough to fight for their country were good enough to live in it. In his final speech – in a passage which angered a listening John Wilkes Booth – Lincoln suggested that some black people should vote, showing that he’d changed considerably from his insulting leave-America remarks in August 1862.

Between the August 1862 meeting and the Booth-provoking speech, when Lincoln’s views were still in evolution, several black visitors came to Lincoln to have serious discussions (not just lectures) about the state of the country. Frederick Douglass visited the White House on more than one occasion to urge Lincoln to greater boldness in vindicating black rights. Douglass was accustomed to disrespectful treatment from whites, even whites who were fellow-abolitionists. But Lincoln impressed Douglass with a courteous and friendly attitude, such as the President might assume in talking to a white person.

Lincoln also showed his genius as a politician – saying “no” in a charming and ingratiating way. When Douglass pressed for the appointment of black officers to lead the black troops, Lincoln said he’d be happy to sign commissions for black officers – if Secretary of War Stanton sent the commissions for Lincoln to sign. The thing is, Lincoln wouldn’t order Stanton to send commissions, and Stanton wouldn’t do it on his own initiative, so Lincoln’s answer was basically a no. Even this slipperiness didn’t sour Douglass on Lincoln.

Also, Lincoln, on paper, had authorized reprisals against Confederate prisoners if Confederate forces killed or enslaved black Union soldiers. But Lincoln indicated to Douglass a squeamishness about actually carrying out such threats, especially when it came to killing Southern hostages. Reprisals might lead to a cycle of killing against victims who were personally innocent. Douglass believed that only by enforcing the reprisal policy could the Union protect its black soldiers against enemy atrocities. Yet Lincoln did not enforce the reprisal policy, and black soldiers continued to face far more risks than white soldiers if they fell into Confederate hands.

Without going over every meeting covered by Professor White, black visitors who came to the White House for policy-related discussions tended to react as Douglass had – with gratified surprise at being treated on equal terms vis-à-vis white visitors. Some of the fulsome praises in black visitors’ accounts are revealing – not only of Lincoln’s personal friendliness but of the insulting and demeaning treatment these black leaders were otherwise accustomed to getting from white people. And of course, by the time of most of these meetings, Lincoln had ordered the freeing of most U. S. slaves, and had urged the freeing of still others. Would it be too much to say that long-suffering black leaders went into these meetings giving Lincoln more benefit of the doubt than in the case of some other white man?

Policy discussions didn’t mark the only occasions in which black people visited the Lincoln White House. Professor White describes Lincoln’s kindly relations with his black servants, his help to a black woman begging at the gate, and so forth. This all shows Lincoln to be a very kind man, but such stories could probably be gathered about many “benevolent whites.” These particular stories don’t show Lincoln making a distinctive contribution to race relations in the broader sense.

Professor White notes, with regret, that Lincoln sometimes allowed racial discrimination at the White House. This was not a consistent policy – some daring black visitors broke the color barrier at White House receptions, which previously been as all-white as the house itself. But at the White House New Year’s ball in 1865, cops who were guarding the door kept blacks from attending as guests. The cops may have been acting without specific orders, but to coin a phrase, Lincoln bore “command responsibility” for the policies of his own White House.

The most intriguing parts of the book, as I’ve suggested, are about those black leaders like Frederick Douglass who came to the White House to discuss policy with the President. Except with the emigration speech, the Great Emancipator treated these visitors as fellow-citizens to be consulted about urgent issues facing the country – a first for a White House denizen.

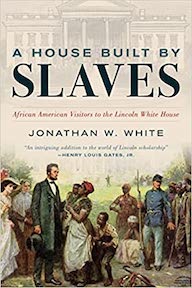

A House Built by Slaves

Jonathan W. White

Rowman & Littlefield

249 pp. with notes and index; $26.00

Sounds like a very intriguing book that takes a “behind the curtain” look at Lincoln’s values while in the White House. Does the book mention how his Republican platform on free labor evolved while in office? The free labor ideology contradicted the institute of slavery, and though I can’t cite the speech, Lincoln had voiced some sentiments toward equal economic rights for blacks, though not exactly condoning civil or political rights before he became president. Something along the lines of “every man deserves to work for his bread” which aligned with the free labor thought. I personally was shocked when I learned in my own studies of Lincoln’s support of colonization, but that “solution” to the slavery question was so widely accepted by many anti-slavery and abolitionist thinkers of the age.

I’ll have to add this to my wish list. Thanks for the review!

Lincoln was not a racist

a skilled politician yes, racist no.

Entirely too many folks are posting false comments

Lincoln loathed slavery not because of the artificial racial barriers, but because it deprived a man, or woman of the value of their labor. The title of the book in many ways reflects this cruel paradox. The fact that the labor was enslaved in no way, however, diminishes the quality of the work. And it should never be forgotten that in the 18th and mid 19th century slave labor was common in Africa and Asia, and that among Islamic cultures it was tinged with an aura of superior/inferior as well.

I am a definite Lincoln scholar and fan, and this book and review post touches on one of my fave subjects connected to the Civil War/War Between The States and related era, Black American colonisation.

Now, it is true that Black American colonisation as advocated by a large segment of the American Colonisation Society and other White Americans whom supported this drive did so for outright racist reasons, as did a fair to high number of Abolitionists and especially, Northerners. The opposition to slavery often took the form of opposing that it had brought Africans to America, at all. The solution as this wide group of people saw it was to ‘send the African back home’, so to speak. And alternatives such as Central and South American were offered, (during the war, Denmark offered to re-settle emigrant Black Americans in their Caribbean island possessions.)

The above is very true; you can see a good deal of evidence of the eyes that looked on Black colonisation through the scope of racism and that this would ‘get rid of a problem’.

It is true that Lincoln looked upon Black colonisation through this very prism for a long time and when you realise this in combination with other evidence, you can clearly see that for a large segment of White Northerners, their opposition to slavery in no way, shape or form meant they were any less racist; in truth, the desire to halt the expansion of slavery/end it, combined with Black colonisation meant something else entirely, that this was an alternative form of White Supremacy, that of White Northerners.

Lincoln’s hero, Henry Clay, aspired to Black colonisation through this perspective, too.

BUT!, and this is a big but, there was another ‘fork in the tree branch’ regarding Black colonisation and it was this perspective of it that Lincoln came to embrace.

Lincoln very likely did not ever give up the idea entirely of Black colonisation, as Benjamin Butler stated and as Philip Magness wrote in his book; but it is very true that how Lincoln viewed the scheme through DID.

The other fork that is so overlooked today about Black colonisation was this: This was a way of convening equality for Black Americans abroad, to recognise them with the same status and rights as what White Americans abroad would enjoy from the end of the Revolution to almost the start of WWII. The other fork meant that Black Americans were seen by themselves and others, (including the US government!), as AMERICANS abroad.

White Americans whom left America in the timeline above did not see themselves as leaving America; they saw themselves as ‘bringing America to the world’. Such persons and parties were seen as harbringers and ‘de facto agents’ of American values and polity by their very being wherever they settled and were seen by foreign governmental bodies and citizenry as ‘Americanising influences’ whom effected change wherever they settled and went, by their living status as Americans, often distrusted as ‘fifth column’ elements.

The examples of this are endless, Texas being the most famed example, but the process starts much earlier than that, with how after the Revolution, many White Americans whom had supported this took up the British Crown’s offer of free land in what is now Canada. When the War of 1812 started, the Congressional ‘War Hawks’ were sure that these American settlers would rise up and support the land of their origin, and the British/Canadians had fears of this, too.

In Australia throughout the 19th Ce., Americans had evoked an enormous impact on the development of the country, politically and in terms of militancy, (Mexican-American War veterans and other Americans had been some of the foremost persons in the Eureka Stockade and the authorities there were drastically concerned with the ‘American influences’ that these evoked). American concepts eventually found themselves into the Constitution and other incidents like the Catalpa Affair.

Other Americans had had an enormous impact around the globe, such as Robert E. Peary in the High Arctic, the Americans in British Columbia during the Cariboo Gold Rush and the Yukon during the Klondike, on the Canadian prairies, (one of the major reasons the RCMP was created was to protect Canadian sovereignty there and from the Whiskey Traders), Central and South America, like David Walker of Tennessee, Henry Morton Stanley in Africa, American whalers in New Zealand, Winston Churchill’s mother, Eamon De Valera of Ireland and all the Fenians and proto-IRA raids after the war from America. Etc, etc, etc.

The ‘other fork’ of Black Colonisation was to see Black Americans as fitting into this neatly. It was a way of convening to them the same equality, rights and status which their White counterparts enjoyed for almost 150 years. Lincoln became aggressively adamant that the only Black Americans whom would leave America would be those whom wanted to leave and they would do so with the full support and recognition of the American government. That’s why in 1863, when Lincoln asked the British for some land for a settlement for USCT-veterans and their families, the British refused; they feared that landing trained and professional soldiers and their families on their territory would soon see the American flag run up the pole and no choice but to either go to war or concede it an American territory.

For when you look back over the records, what you quickly see is that not all Black Americans agreed with those whom Lincoln met with in August of 1862, and again that year at Christmas, at all; a lot of Black Americans thought that emigrating ‘back to Africa’ and abroad was a VERY good idea. And when you review the evidence of what happened when they did, you quickly see that they were looked at in exactly that light; as Americans abroad and all that that conveyed.

-Starting in the 1820s, in newspapers of what is now Canada, the arrival of Black Americans fleeing slavery were described in Canadian newspapers as bringing, ‘American influences’ with them.

-John Joseph was a Black American from New York and a miner in Victoria, Australia. He and a number of other Black Americans fought at the Eureka Stockade and he was the first to be tried for treason by the authorities there, citing in part his Americaness as being a problematic influence. His acquittal was an absolute landmark, along with the others, in the treason trial as heralding Australian democracy.

-When Lord Trenchard, the later founder of the Royal Air Force, led an expedition of the British in Africa

-MW Gibbs had been a colleague of Frederick Douglass and attempted settlement by Black Americans in California. They were driven from there and eventually settled in the (then) two separate British colonies of British Columbia and Vancouver Island, forming a rifle militia unit in the latter. They constantly faced suspicion as being ‘American influences’ and distrusted for this, despite again and again pledging their loyalty to the British Empire. Gibbs would eventually be one of the first Black Americans elected to public office on the continent. His autobiography is, ‘Shadow & Light’, and there is a score of info about him and the other settlers.

He later returned to America about 1867 to take up a Reconstruction position in Arkansas.

-Martin Delany led several attempts to form colonies in Africa for emigrant Black Americans, attempting to arrange treaties with the local African tribal nations. He also lived in Canada and during the war, he became the highest-ranking Black American in the US Armed Forces, being commissioned as a Major. He met with Abraham Lincoln in February of 1865, wherein he received his commission. During their conversation, Lincoln stated he knew all about Delany and respected him, but they never once broached the subject of Black colonisation. If Lincoln viewed the scheme only and solely through the eyes of, ‘you and those like you get the heck out of here!’, (which he no longer did), or, ‘I want to create a safe haven for yourself and those like you, as I fear you will never be able to reside peacefully and equally in America’, (which he did to an extent, though at least this perspective was rooted in concern and humanitarianism), then here was the ultimate opportunity to enact Black colonisation in detail. But Lincoln didn’t. This, I would argue, tacitly indicates that Black colonisation was no longer foremost as the plan to be enacted for Black Americans in Lincoln’s mind following emancipation, exactly as he had asked Frederick Douglass during the 1864 election to prepare a ‘rescue plan’ to extricate as many enslaved Black Americans as possible out of bondage and evacuate them to Union-held areas.

Timmy Hodge portrays Delany and his knowledge and presentation as the Major is simply mind-blowing. I can not more heavily encourage all whom would want to know of Delany to contact Timmy.

https://uniongenerals.org/meet-the-generals/major-martin-robinson-delany/

&,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bRa82atFquc

[Accessed 14 July 2022].

Delany wrote several works and was also involved with newspapers, he was a medical doctor and like Gibbs, was heavily involved in education for Black Americans. His espousal for Black Colonisation was one reason he and Frederick Douglass eventually parted ways. Delany’s biography is available for free online, ‘Life & Public Services of Martin Delany’, by Frank A. Rollin

-Thomas Morris Chester, like Delany, was another Black American whom was heavily involved in Black colonisation. Born in Pennsylvania, he was very educated and made about five trips to Liberia and for all his life, promoted this. He was highly historic, being among the first Black Americans to be armed, when made an commissioned officer in the state militia to help repel the Army of Northern Virginia in 1863 and was the only Black American reporter for a major newspaper on either side during the war. His articles for the ‘Philadelphia Press’ are some of the best information on not just the USCT, but of life and events during the war and shortly after. He also became the Commander of militia in Louisiana in Reconstruction and fought at Liberty Square. He was central in helping Liberia as a colony and even published newspapers there and helped found a university and other educational facilities. He also became a ‘de facto’ American consul at the court of the Russian Czar in the winter of 1867-68, (give or take a year), and was the first Black lawyer to graduate and practice in the U.K., (he practiced there opposite Judah Benjamin and Chester’s skill in the courtroom was heavily noticed).

The book, ‘Thomas Morris Chester: Black Civil War Correspondent’, by R.J. Blackett ought be compulsory reading and/or curriculum material in every Civil War university course in the world.

With all the above and more like Black Americans abroad, you can see ‘American’ notions and influences shaping everything they do and these being seen in and about them by the foreign powers that be. It is true that Black colonisation could be a vehicle of racism, there is no denying that. But it was not the ONLY means of either at the time or in posterity viewing the phenomenon. It was also a way of convening equality, status and rights to Black Americans.

I am not sure we read the same book as evidenced by your comment, “The book comes out at a time of debate about whether Lincoln was a racist. The short answer is “yes, but as the war went on he got a lot better.” Nowhere does the author state Lincoln was a racist. Neither could I find your quote, which is without citation, anywhere in the book.

A more accurate statement of the author’s argument might read; White contends that with the exception of a stunningly preachy and “terribly condescending” (p. 43) meeting with African American leaders, where he lectured them on the benefit of their leaving the United States for some unknown colony in Central America, Lincoln’s further interactions African Americans were uniformly respectful and substantial.

The author argues that throughout his presidency, Lincoln displayed a “willingness to welcome black leaders into his orbit when discussing great matters of state” (p. 50). White notes that in a 19th century context, Lincoln took extraordinary political risk with Democrats by hosting African Americans in the White House — Frederick Douglass, Daniel Paine (leader of AME Church), Sojourner Truth, former slaves and U.S.C.T troops. Finally, this was a time when even shaking hands with African Americans was deemed inappropriate in polite society. Yet the President took time to talk to and shake hands with African American callers and formerly enslaved people on the street treating “them with dignity and respect … as he would a foreign dignitary or congressman” (p. 176).

If this comment about Lincoln being a racist who “got a lot better as the war went on” is your personal view, i suggest a little more scholarship on Mr. Lincoln is in order. While African American leaders — Frederick Douglass, W.E.B. Dubois — have often criticized President Lincoln, and sometimes justifiably so, no serious historians make a case that he was a racist.

I was quoting myself and never claimed otherwise.

Now, the thing is, I went to the uttermost verge of hero-worship regarding Lincoln, but apparently, if I am to avoid receiving personal insults, I must also engage in *blind* hero-worship.

I’ll limit myself to citations to the very book under review, which you claim you read also:

“To be sure, Lincoln infamously – and unfortunately – declared at the Lincoln-Douglas debate at Charleston, Illinois in 1858 that ‘I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races.’ Nor did he claim to advocate granting black men and women the right to vote, hold office, or sit on juries. Still, he continued, ‘I say upon this occasion I do not believe that because the white man is to have the superior position the negro should be denied everything.'” (p. 13).

“However, in one infamous case Lincoln argued on behalf of a Kentucky slave owner who had brought slaves into Illinois. The *Matson Slave* case has proved a stumbling block for scholars who wish to depict Lincoln as antislavery from the beginning of his political career, although some have ventured plausible explanations for why he may have taken the case. For instance, Lincoln might have been following the advice of George Sharswood, the eminent nineteenth-century legal commentator, that lawyers ought ‘not to pass moral judgments on potential clients'” etc. (p. 7)

These quotes appear near the very beginning of the book, increasing the likelihood that you read them.

My entire review shows how Lincoln grew so far in the direction of egalitarianism as to help persuade Booth to kill him.

In short, Lincoln needs no defense from me.

thanks Max … i wasn’t expecting a defense of Lincoln — that’s the author’s job, not yours … instead, your opening salvo calls President Lincoln a racist “who got better” during the war … that’s an interesting personal opinion, but just not appropriate for a scholarly review.

in the reviews i have read, the reviewer states the author’s argument, how the author makes his case, and evaluates whether or not the author is effective … then, depending on the length of review, commentary on sources, organization, writing style, and who might enjoy reading the book are appropriate.

that’s it — the lecture is over, schools out, and i eagerly await your next review … and thanks for writing this review by-the-way — not an easy task as they take some time … i mean that sincerely.

PS — this ain’t personal my friend … but when you (not the author) call President Lincoln a racist you can expect some respectful push-back … that’s what makes the blog so much fun! 🙂

That’s OK, it’s not as if the Civil War were some neutral and noncontroversial field. I had wondered if I came across as a tad defensive but I’m glad you didn’t take offense at my defense.

It’s really a great book and if my personal comments (which are not the author’s fault!) took away from analyzing the book I shall try to be a tad better in future. My thought was I’d build up from what I saw as a necessary acknowledgement of where Lincoln started from, preceding an analysis based on the book to show how Lincoln really transformed (not “grew,” transformed) while in office.

What gave me an extra appreciation of Lincoln many years ago was that as I studied his contemporaries I realized that for the most part they didn’t live up to his standard, so I was actually converted to the conventional wisdom of him as the Great Emancipator. (But also he was largely Honest Abe, so if he said something unfortunate I regrettably assume he was telling the truth of his position at the time).

Peace and goodwill,

Max

I am of the opinion that 99.9 % of the Caucasian population in the US in 1860 was racist to a degree. I guess it depends on “your” definition of racist.

I don’t look at the “Matson Slave ” case as a stumbling block Lincoln was a professional, a lawyer. One definition of professional is…a person you go to when you have a problem, for redress. Lawyers are professional, physicians are professionals. And being a professional, you defend the position of your client, no matter your beliefs.

For instance, the ACLU defended the right of Nazis to march in Skokie Illinois

And I know you all are aware of the fact that the law of the land, the United States Constitution, was a racist document, in 1860. Why? Because of the 3/5ths clause which gave the slave holding states more representation in the House of Representatives ,more votes in the Electoral College, and thus the ability to nominate judges to the Supreme Court who would back the institution of slavery The 3/5ths clause affected all 3 branches of our Government. Even the 2nd Amendment provides for a militia which the Congress could call upon to put down any (slave) insurrection.

If there was one thing slave owners feared, it was a slave insurrection. Even during Braddock’s march to the Monongahela, Virginia slave owners were reluctant to part with their militias.

It seems to me inescapable that most persons of many stripes were “racist” in 1860. In a time when many educated Englishmen were convinced the Irish were inferior simply because the circumference of their heads indicated poor mental ability and the like. Science was so limited at that time, or hat passed for science.

But, more so because “racism” is not a discrete state of mind. It is not an either/or proposition. Racism, like all the -ism’s is a continuum. Some folks are more racist than others. Some folks are racist in certain situations, and not so much in others. Those of us, like myself who sue folks for discrimination see this phenomenon every day. A white manager who hires a brown man may be fine with that brown man – until that brown aspires to a white collar job. Females in the work place may be fine until they become pregnant. Had a lawsuit not that long ago, where a well-known ex-football start had a nice business relying on the internet. He needed an IT expert. He hired a blind IT expert who had excellent credentials. The former football star would on occasion make the worst fun of the IT expert, play with his walking cane, walk with his eyes closed, etc. On paper, it looked like the former football star was fine with disabled people. He hired one, after all. But, in reality, that was the worst sort of prejudice one could find. The -ism’s are complicated.

Racism is nuanced. It is not an either/or deal. I defer to Max or the author on their knowledge of Lincoln. But, even my lesser reading of Pres. Lincoln suggests he likely evolved in his understanding of racial issue. But, that does not make Lincoln an early version of a 1960’s era civil rights activist. This is a history blog, after all. We expect historical studies, not modern ones.

Tom

Nice comment.

From my readings, Lincoln seems to evolved too.