Nobody Can Truly Understand the Battle of Gettysburg Without a Solid Understanding of the Battle of Chancellorsville

Although I am best known as a “Gettysburg guy,” I have long been absolutely fascinated by the battle of Chancellorsville. Last month, I spent 2.5 days leading a tour of the sites associated with the Chancellorsville Campaign for several fellows who hired me. The preparation re-focused me on the battle, and my primary theme for the tour was “in order to truly understand Gettysburg, you have to have a very solid understanding of Chancellorsville.” It was one of our major focuses, and after finishing the tour, I am more convinced than ever that this is a true statement. I’ve written about this topic previously on my blog, but I have come to further conclusions that only further validate my thoughts on the subject.

Although I am best known as a “Gettysburg guy,” I have long been absolutely fascinated by the battle of Chancellorsville. Last month, I spent 2.5 days leading a tour of the sites associated with the Chancellorsville Campaign for several fellows who hired me. The preparation re-focused me on the battle, and my primary theme for the tour was “in order to truly understand Gettysburg, you have to have a very solid understanding of Chancellorsville.” It was one of our major focuses, and after finishing the tour, I am more convinced than ever that this is a true statement. I’ve written about this topic previously on my blog, but I have come to further conclusions that only further validate my thoughts on the subject.

The most obvious implication for Gettysburg is the mortal wounding of Stonewall Jackson. When his own men inflicted a mortal wound on Jackson, it meant that there would be tremendous changes ahead for the Army of Northern Virginia. At the time of the battle, the ANV consisted of two extremely large corps, commanded by Jackson and James Longstreet. Most of Longstreet’s command was not at Chancellorsville; all but McLaws and Anderson’s divisions were besieging Suffolk. It appears that Robert E. Lee had already decided to restructure the army into three corps even before Jackson’s wounding, but doing so would have required identifying only one new corps commander.

After Jackson’s mortal wounding, Lee now had to identify two new corps commanders, and not just one. He restructured the army by transferring some units from Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s First Corps and units from Jackson’s command to create the brand new Third Corps. Other units from the defenses of North Carolina were added to the Second and Third Corps as well. Only Longstreet—Lee’s “warhorse”, as he called Longstreet—had any experience commanding such a large body of men. The other two—newly promoted lieutenant generals Richard S. Ewell and A. P. Hill—were both returning from wounds (Hill was wounded with Jackson by friendly fire) and both were in questionable states of health. Hill was the likely candidate for promotion since he had excelled at division command, but he proved to be nearly a non-factor at Gettysburg due to his delicate health. Ewell, who had lost a leg to a combat wound, was understandably not the same man after his wound. High strung and nervous under the best of circumstances, Ewell eventually proved incapable of handling the stress of corps command and was unceremoniously relieved of command after a near nervous breakdown during the 1864 Battle of Spotsyvlania Court House.

I have never been a fan of “what if’s”, and the question about what Jackson might have done at Gettysburg drives me nuts. My normal response is “Had Jackson been at Gettysburg, he would have been in an advanced state of decomposition.” However, one point about this bears making. Lee was used to giving Jackson vague, discretionary orders with a high degree of confidence that Jackson would make the right decisions. Rather than adjusting his style to reflect the personalities of Ewell and Hill, Lee continued the same practice with Ewell, in particular. At Gettysburg on July 1, Lee gave Ewell a vague, discretionary order to take Culp’s Hill “if practicable.” That undoubtedly had a different meaning to Ewell than it would have had to Jackson.

Others argue that with the passing of Jackson, the Army of Northern Virginia lost its offensive punch. While I don’t necessarily agree, there is no disputing the fact that the Army of Northern Virginia would never again be the same. The restructuring of the army and its being broken out into three corps meant that it took the field in its most important battle with two untested and inexperienced corps commanders instead of one. There is no way to determine just how critical that was, but there is unquestionably no doubt that it had a significant impact on the outcome of the battle.

I also believe that a deep understanding of Chancellorsville also adds insight into what Lee was trying to do at Gettysburg. Even after the great tactical success of Jackson’ s flank attack, the Federals still had a decent chance to fight Chancellorsville to a tactical draw if Hooker had not panicked, ordered some questionable reactive moves, and eventually retreated from the field. Confederate forces again had a major tactical victory on the first day at Gettysburg and Lee followed up on the second day with his divided forces attacking at several points involving both of Meade’s flanks. In my opinion, Lee’s victory at Chancellorsville involved a collapse of the morale and moral fiber of the Union high command more so than a collapse of the Union fighting men. An attempt by Lee to do something similar to Chancellorsville failed at Gettysburg because Maj. Gen. George G. Meade—Hooker’s successor as commander of the Army of the Potomac—and his lieutenants were far more resolute and had confidence in their ability to shift forces to blunt Lee’s thrusts than was Joe Hooker, who admittedly lost his nerve.

At the same time, the lopsided Confederate victory had one very real and unforeseen consequence. The combination of the two stunning victories at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville made both Robert E. Lee and the men who followed him into battle believe that they were invincible. Lee’s plan at Chancellorsville violated virtually every conventional rule of war: he was outnumbered more than two to one, he divided his army in the face of the enemy, and he took the offensive against the accepted odds. Incredibly, those incredibly risky gambles paid off, and his army thrashed Hooker at Chancellorsville, even if it came at a frightful toll. Such success inevitably made both Lee and his troops believe that they were invincible, and those men paid the price for that arrogance eight weeks later at Gettysburg, especially those who led the Pickett-Pettigrew-Trimble charge on July 3, 1863.

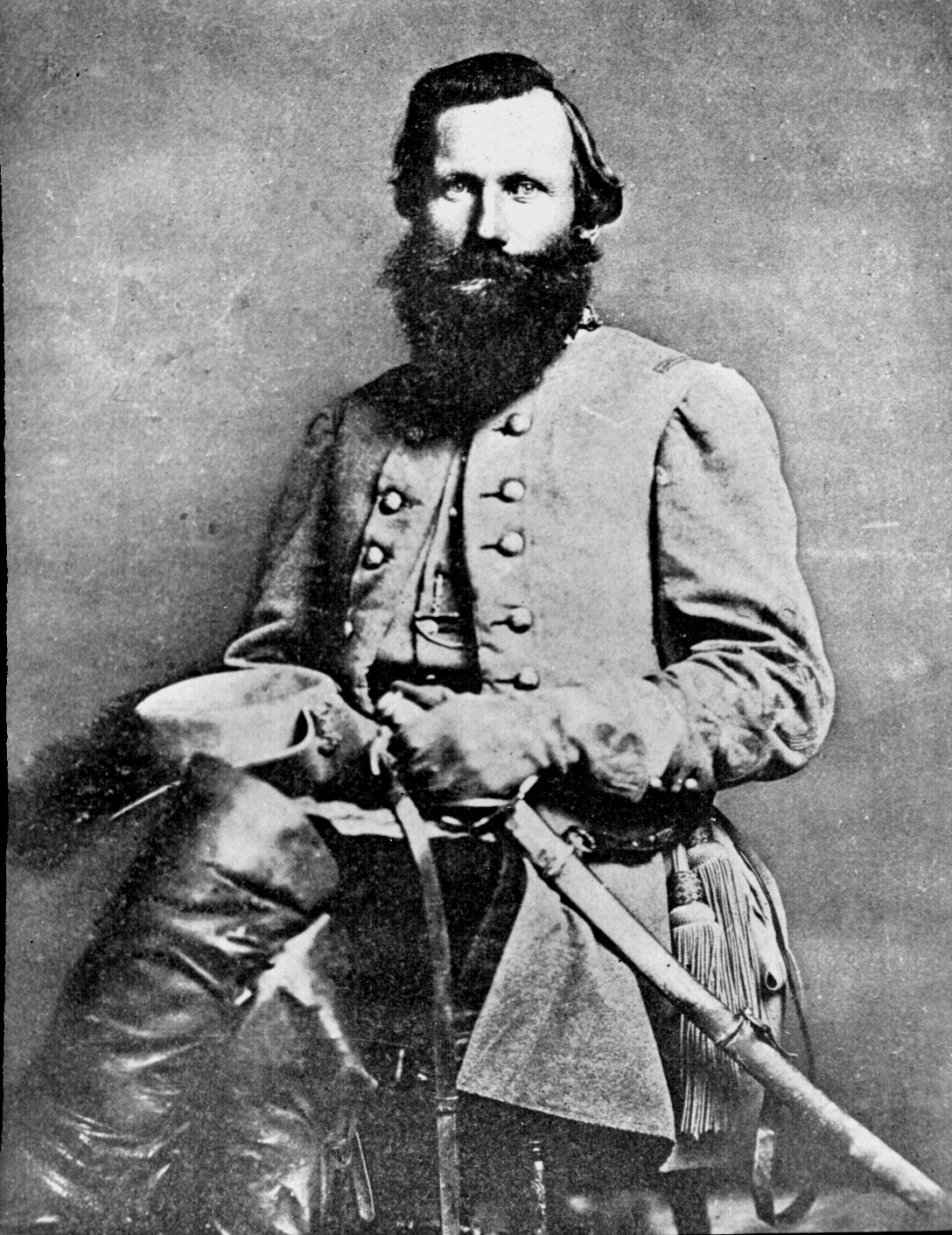

Courtesy LOC

When both Jackson and Hill were wounded at Chancellorsville, the next ranking officer in the corps, Maj. Gen. Henry Heth, had just been promoted to divisional command and was in no way prepared to assume command of a very large corps. Neither was Maj. Gen. Robert E. Rodes, who was also brand new in divisional command. Rodes recognized his shortcomings and deferred command to Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, Lee’s cavalry chief. To Stuart’s undying credit, he performed magnificently in that role, leading Jackson’s battered men in a hard day of brutal, bloody fighting on May 3. Stuart wanted permanent command of the corps and felt he had earned it by virtue of his fine performance at Chancellorsville. Lee, however, evidently felt that the army was better served by having Stuart remain as the eyes and ears of the army, and returned the cavalier to his regular command after the battle. Some armchair psychologists have speculated that Stuart’s disappointment over not being given permanent command of Jackson’s corps caused him to become determined to do something spectacular in order to prove that Lee was wrong. Personally, I don’t buy this theory for a moment, but it’s very persistent and it’s worthy of attention.

Just as important, the heavy losses among the Army of Northern Virginia’s brigade commanders changed the army’s complexion at Gettysburg. As just one example, Brig. Gen. Frank “Bull” Paxton, Jackson’s successor in command of the legendary Stonewall Brigade was killed on May 3 during the heavy fighting for the Chancellorsville intersection. Brig. Gen. James Walker took command of the Stonewall Brigade, which took little part in the Battle of Gettysburg.

Lee took 28 brigades into Chancellorsville. Nine of those brigades lost their commanders during the battle, and of those nine, three brigades lost multiple commanders. Lee also lost 64 of 130 regimental commanders at Chancellorsville. As a result of those losses, many of Lee’s brigades went into battle at Gettysburg with inexperienced unit commanders.

The Army of Northern Virginia went into battle at Chancellorsville with approximately 61,000 men. It took nearly 14,000 casualties there, or nearly 22% of the army’s total strength. This, in turn, even with the return of the rest of Longstreet’s command and the addition of some reinforcements, the Army of Northern Virginia’s combat strength was significantly reduced by the time that the Battle of Gettysburg opened on July 1. It meant that Lee’s army, which was clearly the aggressor at Gettysburg, had a significant numeric disadvantage.

By contrast, the Army of the Potomac numbered nearly 134,000 at the outset of the Chancellorsville Campaign. Hooker sustained 17, 197 casualties at Chancellorsville, or just over 10% of his army’s total strength (although a significant number of two-year regiments saw their enlistments expire just after the battle, thereby greatly reducing the strength of Hooker’s army). Even with the mustering out of the two-year regiments and the Chancellorsville losses, the Army of the Potomac took the field at Gettysburg with a significant numeric advantage. Further, the Union army did not take the heavy losses in its command structure that Lee’s army suffered, even though Hooker’s army suffered two division commanders killed (Hiram G. Berry, Amiel Whipple) and another one wounded (Charles Devens).

Lee’s audacity in defying every accepted rule of warfare at Chancellorsville caused the unlikely Confederate victory there. Lee divided his much smaller army in the face of the enemy and took the offensive even though it was outnumbered more than two to one. He left only 13,000 men in place to hold the body of the Army of the Potomac while sending the bulk of his army off on a daring and perilous flank march. The success of this audacious plan set the stage for the debacle that befell the Army of Northern Virginia on July 3, 1863. The success at Chancellorsville apparently persuaded Lee that his army could not be beaten and that his men could do the impossible as they were asked to do during the Pickett-Pettigrew-Trimble charge on July 3.

In the next installment, we will examine the strategic implications of the results of the Battle of Chancellorsville for the Army of the Potomac.

I have long believed that the most important result of Chancellorsville was Lee’s mistake in understanding what had happened. He thought that his army had beaten the Federal army, and therefore could just about do the impossible; hence, Gettysburg. The reality is that Lee had beaten one man, and one man only: Joe Hooker.

And the officer losses at Chancellorsville place a significant number of new officers in corps, division and brigade command at Gettysburg, where the officer corps takes a beating again. The bleeding of the ANV officer corps continues through the Overland campaign. Lee couldn’t find enough competent replacements at the pace he was losing them.

Sickles move to high ground in the Peach Orchard was directly related to his move off the high ground at Chancellorsville

Again, excellent work by Mr. Wittenberg. Spoken by a true attorney, no fluff, just the facts!