Bivouacs of the Dead

When touring battlefields on my own or leading a group, I always try and stop by the cemeteries that are there – both to meet the men but also to reflect on the events. I try to do this whether the field is in the United States, Asia, or Europe. As I’ve done so (and contemplate future visits), I’ve noticed there’s a definite change in how the large scale of death of the Civil War and the World Wars impacted how the dead are recalled. Let me explain.

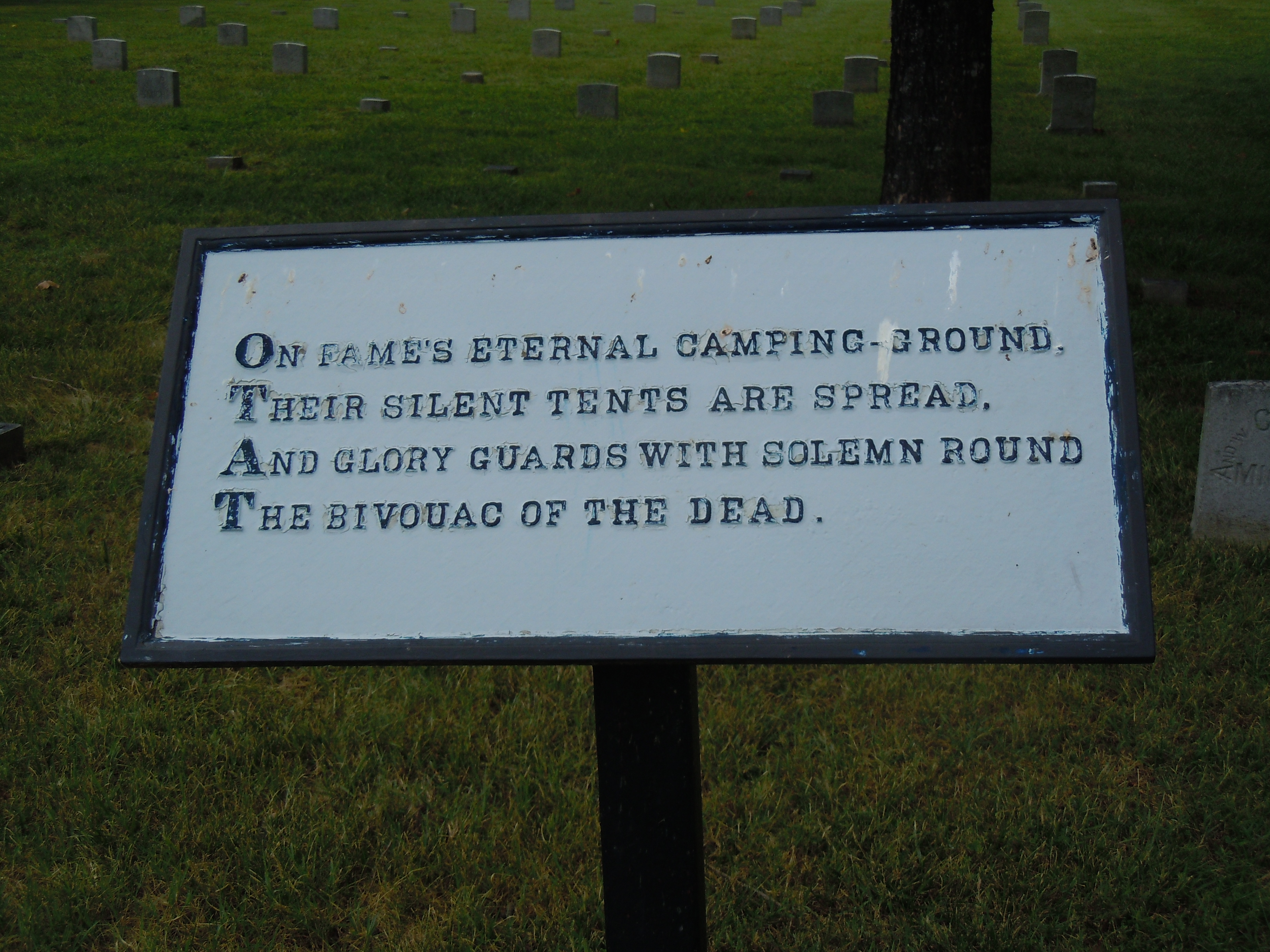

Visitors to Civil War-era National Cemeteries are often familiar with Theodore O’Hara’s poem The Bivouac of the Dead, verses of which are often on display. His poem, written in 1847 to honor Mexican War dead, has a somber tone that encourages contemplation and mourning. The inclusion of his poem sets a fitting tone for the National Cemeteries.

The Civil War was the bloodiest conflict in American history, inflicting death and destruction on a scale never before seen. From May to November 1863, over 116,000 total casualties were sustained in the war, the rough equivalent of the total American losses in the Korean War. While O’Hara took a mourning tone for a smaller war, by 1863 people sought to do more than just mourn – there needed to be some meaning or legacy. Abraham Lincoln addressed this need in the Gettysburg Address, commenting that the dead “shall not have died in vain.”

This need to assign meaning and legacy to battlefield deaths extended into the 20th Century. John McCrae’s In Flanders Fields (which turned 102 on May 2) both caught the contrast of the modern battlefield and issued a challenge from the dead to the living: “To you from failing hands we throw the torch.” It is an exhortation to fight on, but the lines about not breaking faith also suggest something deeper and lasting beyond war’s end or even a single generation.

The Imperial War Graves Commission (now Commonwealth War Graves Commission) echoed this feeling of legacy and permanence with the inscription in every major cemetery: “Their Name Liveth For Evermore.” American overseas cemeteries took up a similar line, exhorting visitors to “Think not upon their passing remember the glory of their spirit.” American unknowns rest “In honored glory.”

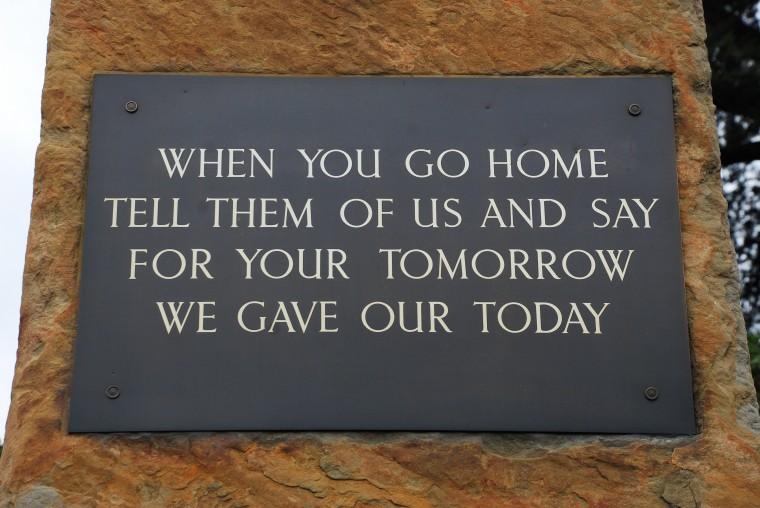

World War II’s famous and profoundly moving “Kohima Epitaph,” displayed on the 2d Division Memorial in Kohima, India, takes it a step further. (See picture at top.) It is a missive from the dead, but also contains a clear charge to the viewer to “tell them of us” and the dead’s sacrifices. Kohima came in 1944, 97 years after O’Hara wrote his poem, and is the clearest contrast of how the mass deaths of the Civil War and the World Wars affected the protagonists and their memory of war dead.

Bottom Left: The British Cemetery at Thanbyuzayat, Burma (Myanmar).

Bottom Right: Lines from O’Hara’s poem displayed in the Fredericksburg National Cemetery, Fredericksburg, Virginia.

Reblogged this on seftonblog.

O’Hara was a Confederate.

It is interesting and compelling to compare war monuments of different eras and their inscriptions– for me especially compelling on this Memorial Day, when I happened to open Chris’ blog posting. Moving through history from Chris’ example of WWII monuments, I offer a link to a description of the Vietnam Veterans Monument in Pittsburgh: http://www.pghmurals.com/Vietnam-Veterans-Monument.cfm. The webpage includes photos, an interpretation of the monument and a picture of the brass plaque with the poem copied below, written by U.S. Marine veteran T.J. McGarvey (Vietnam, 1967-68). Erected in 1987 (five years after the dedication of The Wall on the National Mall), this is a monument to men and women killed during the war, as well as to the service members who came back. The memorial and the poem offers remembrance for those killed-in-action as well as hope for new beginnings for those returned. It is just one example of how war monuments evolve, from war to war through history. And from year to year. Contrast the Pittsburgh monument to The Wall.

WELCOME HOME

Welcome home to proud men and women

We begin now to fulfill promises

To remember the past

To look to the future

We begin now to complete the final process

Not to make political statements

Not to offer explanations

Not to debate realities

Monuments are erected so that the future

might remember the past

Warriors die and live and die

Let the Historians answer the political questions

Those who served – served

Those who gave all – live in our hearts

Those who are left – continue to give

As long as we remember –

There is still some love left.

T.J. McGarvey

Outstanding – thanks for sharing. I’ve never been to this memorial, but next time I’m in Pittsburgh I will have to stop by.

And thank you Chris for your thoughtful piece which got me thinking about this. If you are interested in pursuing this topic further, check out “Monument Wars: Washington, D.C., the National Mall, and the Transformation of the Memorial Landscape” by Kirk Savage. It’s a fascinating study of the evolution of monuments and public remembrance as seen through the lens of the history of the National Mall. http://www.ucpress.edu/book.php?isbn=9780520271333

Thanks! I’ll check it out.