BookChat with Cody Marrs, author of Not Even Past

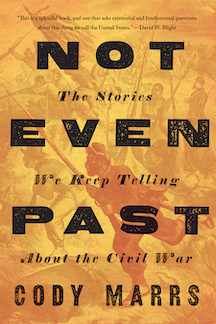

As a big fan of the Civil War in pop culture, I was especially looking forward to Cody Marrs’ new book Not Even Past: The Stories We Keep Telling About the Civil War, which deals with the ways “the story of the war has been retold in countless films, novels, poems, memoirs, plays, sculptures, and monuments.” The book was published this year by Johns Hopkins Press (find out more about it here). Dr. Marrs was kind enough to to take a few minutes to chat with me about his book.

As a big fan of the Civil War in pop culture, I was especially looking forward to Cody Marrs’ new book Not Even Past: The Stories We Keep Telling About the Civil War, which deals with the ways “the story of the war has been retold in countless films, novels, poems, memoirs, plays, sculptures, and monuments.” The book was published this year by Johns Hopkins Press (find out more about it here). Dr. Marrs was kind enough to to take a few minutes to chat with me about his book.

1) I’d like to start with the book title, if I can, which is a reference to a famous William Faulkner quote: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” How did you decide to draw on that as inspiration and context for your book?

Well, I’ve always enjoyed Faulkner’s writing, and Faulkner has played a vital role in the consolidation of Civil War memory. So that’s part of the reason I start there. But I was also drawn to the idea conveyed by the quote, which sums up—better than anything else as far as I’m concerned—the Civil War’s non-resolution in such a succinct and indelible way. After spending years poring over the Civil War and everything it left behind—the books and films, the statues and legacies—I came to see it as a live conflict, albeit one that’s experienced differently now than in the past.

2) How does your work situate itself among other memory studies of the war, such as David Blight’s Race & Reunion or Gary Gallagher’s work? (I saw that Blight wrote a nice blurb for you, BTW!)

I have learned a lot from that work. Actually, what first drew me to the Civil War—what got me hooked—was the work of David Blight, Gary Gallagher, Alice Fahs, and other scholars who study Civil War memory. There are two things in particular I learned from them, which inform nearly everything I do. First, cultural memory is anything but natural; it’s something that’s made and continually remade. Second, you don’t simply get history and then memory, in a neat sequence. There’s a feedback loop between the two, and that’s what endows literature and the arts with their power—they tap into this enduring struggle we call “the Civil War.” If there’s a difference between those books and my own, it’s mostly just a matter of emphasis: I’m inordinately fascinated by stories. I’m addicted to narrative. Not Even Past began as an attempt to reverse-engineer the defining stories about the war and figure out why they became so effective.

3) The book talks about the different ways the war has been remembered and memorialized: an emancipatory struggle, a divisive fratricide, a fight for Southern independence, a dark period defined by its brutality, and others. Is there truth to all of these versions, or are some “truer” than others?

The narrative of emancipation is the only one that faithfully captures the struggle’s underlying historical spirit. From the beginning, it was a fight over slavery; by 1863, it was also a fight over the possibility of multiracial democracy. The other narratives tend to occlude that, in one way or another. But they do contain kernels of truth. (If they didn’t, they never would have become so influential.)

The Civil War was mostly fought in the South and it was devastating for many of the white people who lived there. It was inarguably a “dark and cruel” war for those who lost loved ones, and for people whose families were severed, the Civil War was certainly an interfamilial struggle.

It would be easier, politically and psychologically, if there was no gray area, but that’s now how history works. Even the narrative of emancipation contains an element of fiction, since emancipation was never fully secured. As soon as emancipation was proclaimed, black freedom was undermined in both legal and illegal ways and, by the 1880s, most of the advances of Reconstruction had been either attenuated or undone. What that tells me, as a student of this era, is that the Civil War was never truly resolved: it ended an armistice but the war has continued to be waged by other means and in a variety of registers.

4) What or who do you see as the seminal texts or creators that really cemented these different traditions of memory?

It’s hard to pin them down, since the archive is so massive! That was a little overwhelming at first. I wanted to examine the Civil War’s afterlife in American memory not in part but in its entirety—to look at everything said and written from the 1860s through the 2010s—so I found myself awash in tens of thousands of texts. For a while I felt like I was drowning.

But the more I read, the more evident it because that a few particular stories and storytellers have exerted an unusual amount of influence on the Civil War’s memory. Lincoln is a central figure around which all of these narratives revolve. One could spend one’s scholarly life studying how and why Lincoln has been quoted, remembered, and represented, and it wouldn’t be a wasted life. There are Lost Cause versions of Lincoln (Thomas Dixon, Jr., for example, loved Lincoln); revolutionary depictions of Lincoln; stories about Lincoln as our Mourner-in-Chief. The list goes on. The literature of and about Lincoln is a major subtradition of American literature, in my view.

Beyond Lincoln, there are several texts that have played an especially vital role in the war’s remembrance, like Gone with the Wind (both the novel and the film), D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage, and Edward Pollard’s The Lost Cause. One of the interesting things, from my perspective as a literary critic, is that there’s often very little connection between a story’s aesthetic quality and its cultural influence. Birth of a Nation is a terrible film, and most of it is incredibly boring. Evelyn Scott’s The Wave and Margaret Walker’s Jubilee, in contrast, are terrific novels, but they’re rarely read or discussed in the same breath as Griffith’s film.

5) You write that we keep telling these stories “because we thirst for closure,” yet the book also contends “the Civil War is an ongoing conflict.” Is it even possible for us find closure, even a century and a half later?

Great question. I do think it’s possible to eventually find closure—to truly turn the page on the Civil War—but doing so would require reckoning with the struggle’s central paradox: the Union that was rescued in 1865 was the very Union that led to the war in the first place.

Consider this thought experiment: imagine a different country, in a different part of the world, that went through a similar event. Say they staged a revolution and, like the U.S., forged a new country. Then they created a Constitution that, decades later, led directly to a devastating civil war in which both sides claimed be the Founders’ true heirs. Then the winning side, instead of starting over, simply amended the Constitution that had led to the war in the first place. What would we say? We’d probably view their political structure as fragile at best.

From my view, the Civil War is indeed “an ongoing conflict” not only in the realm of cultural memory but also in the realm of politics more broadly. As for what it would take to get to the other side—to truly be post-Civil War—your guess is as good as mine, but I suspect it’s impossible without creating a more equitable and sustainable democracy than we have now.

And here are a few short-answer questions:

What was your favorite source you worked with while writing the book?

Probably Terry Bisson’s Fire on the Mountain. It’s a highly imaginative and evocative novel in which John Brown succeeds. Tubman joins him, they win at Harper’s Ferry, and they spark a revolution which eventually leads to the creation of a new country, Nova Africa. It’s one of the most thrilling narratives of the Civil War I encountered, and it was a lot of fun to write about.

Who, among the book’s cast of characters, did you come to appreciate better?

W.E.B. DuBois. I’d always loved and admired Black Reconstruction, but I didn’t realize, until writing Not Even Past, just how much the Civil War loomed in DuBois’s imagination. He returns to the struggle again and again, in almost everything that he writes, from the beginning to the end of his long career. And some of those writings—such as DuBois’s devastating (and utterly true) essay about Robert E. Lee—are some of my favorite texts about the Civil War.

What’s a favorite sentence or passage you wrote?

“If the Civil War was supposed to be a defining moment in American history, no one ever told Mark Twain. When the violence erupted in 1861, the famed humorist was still Samuel Clemens—an unpublished, 20-something riverboat pilot from the hamlet of Hannibal, Missouri—and he responded with decidedly little interest or enthusiasm.” Sometimes I have a hard time with introductions, and I must have written a dozen crappy versions until I came up with this. I wanted to capture Twain’s sense of removal and provide a setup for his story, “The Private History of a Campaign that Failed.” It took awhile to discover that the only way to do it, and do it well, was to tell a story myself.

Interesting interview, Chris, thank you. Ironically, I just read today a review of this book in the current edition of Civil War Book Review. Speaking of which – perceptive book review by you in the same forum of The Wilderness in Myth and Memory by Adam Petty. You are one busy man!