Soldier-Artists and the Battle Experience (Part I)

This is the first of two posts regarding soldier-artists and their depictions of the experience of battle.

“Pshaw. It’s no use, they can’t picture a battle,” exclaimed the young son of Reverend A. M. Stewart of the 102nd Pennsylvania Volunteers, a recent observer of the battles of Williamsburg and Fair Oaks, as he indignantly threw down a copy of Harper’s Weekly with images depicting those engagements. By 1862’s end, Stewart noted that pictures “of officers with drawn swords riding before their men into battle” led the enlisted men to “shout out with mocking irony; all played out.”[i] It seemed that war pictures, to those who had seen war, weren’t all that war-like.

But armies are composed of individuals, no matter how uniform military officials might attempt to make them, and so some men disagreed. In June 1864, George Oscar French wrote a letter advising his home-circle “to get Harpers Weekly of the 11th June. All the pictures about the Army of the Potomac are very good.” Two months later, he recommended another image for his father’s observation, noting that it was “perfectly lifelike” and could be studied for “ten minutes to good advantages.”[ii] But whilst most of the rank-and-file gauged the accuracy of conventional war images around campfires and in their correspondence, there were those decided to take up pencils and paintbrushes to make their own.

These soldier-artists are generally rendered peripheral in our comprehension of the conflict, despite the prolific outpouring of scholarship in recent decades on both Civil War artwork and the ordinary soldier. Men such as Alfred Bellard, John J. Omenhausser, Robert Knox Sneden, Charles Wellington Reed, Alfred E. Mathews, and Adolph Metzner, all unknowingly contributed to the creation of a collective visual scrapbook that provides insight into the totality of the soldier’s war experience. Much of the artwork is now published, but it rarely receives the scholarly consideration of historians: high-art painting and prominent photographs enjoy their focus. But the soldier’s artwork, no matter how folkloric or even primitive it may appear, holds much potential for analysis. Soldiers weren’t merely attempting to record the sights they encountered. They were making artistic statements about their war experiences.

By briefly comparing two Union soldier-artist’s depictions of the Battle of Stones River, one can gain an appreciation of the ways soldiers employed artwork to convey differing sentiments about the battle experience. Adolph Metzner, a captain in the 32nd Indiana Infantry, and Alfred E. Mathews, a musician in the 31st Ohio Infantry, both made pictures of Stones River, but their subjects, techniques, and intended audiences result in markedly dissimilar images. Metzner produced his image for himself, or at most a close circle of associates or family members. Conversely, Mathews had his ambition set on commercial success, and so his picture would pass through the censoring gaze of the printmakers to be made digestible for the northern citizenry.

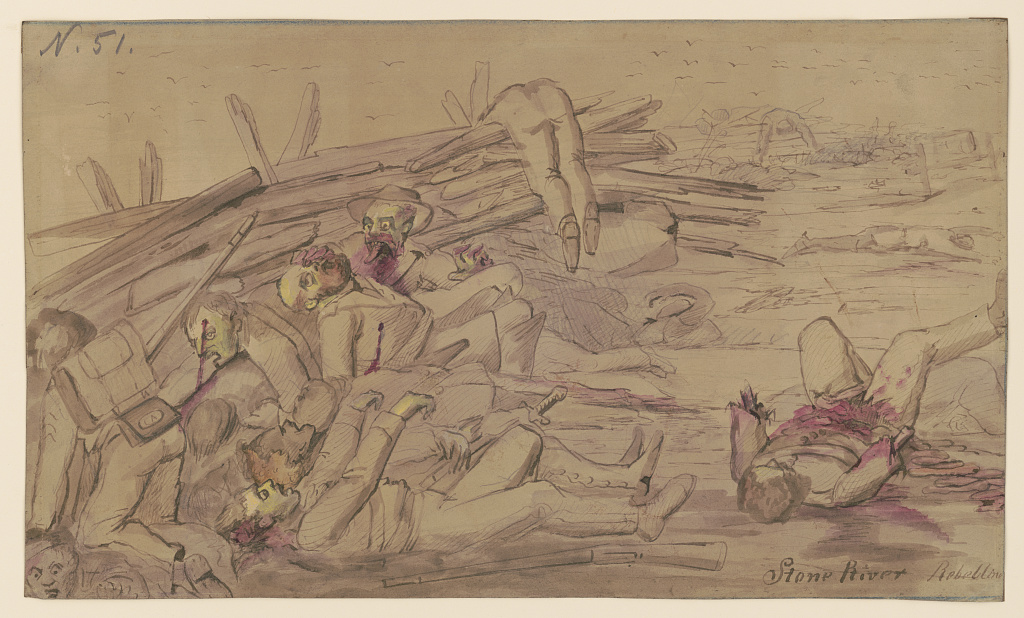

Metzner’s artwork initially exhibited an exaggerated and comical outlook towards the war, but shifted to show the turmoil his regiment experienced following the loss of comrades at Rowlett’s Station in December 1861.[iii] By Shiloh in April 1862, the comedic elements notable in his early works were irretrievable. One of the most graphic of Metzner’s images was The rebel line at Stones River, (Murfreesboro), Jan. 1863. “A cozy corner.” The watercolour depicts a portion of the Confederate line following the battle. Soldiers of all ranks lay pell-mell in heaps. A sword, a symbol of martial authority and of southern honour and chivalry, is notable protruding from the mass of the dead.

There is no formal hierarchy in this death scene. Soldiers are rendered anonymous as they die facedown or are mangled by their wounds from the storm of bullets and shells. The carrion birds gather above the mass as they prepare to feast on the slain, emphasising fears regarding the appropriate treatment of the dead. Civil War soldiers worried greatly about their remains, as one Confederate wrote: “It is dreadful to contemplate being killed on the field without a kind hand to hide one’s remains from… the gnawing of… buzzards.”[iv] Metzner’s scene depicts the soldier’s anxiety over the futility of such improper deaths.

Of particular note in this image is the almost religious and sacrificial symbolism of the figures at centre-left. The pyramidal composition, which is traditionally employed to represent order and stability in conventional artwork, is that which draws the eye to the one soldier’s desperate attempt to grasp at his comrade. It is rendered the most humane act in this depiction of battle. It is no coincidence that the two subjects form a pieta, particularly in view of the similarity in the location of the bullet wound on the officer’s right breast and Christ’s chest wound caused by the Holy Lance. But in this representation, such sacrifice is revealed as useless, for the only reward is to face an impending and unheroic death in Metzner’s paradoxically Cozy corner.

But Metzner’s scene reveals sympathy rather than any hatred for the enemy. This is no exhibition of the triumph of Union military might, but instead a mournful scene illustrating the traumas of modernising warfare. Though new innovations in armament development occurred in the antebellum era, most combat continued to occur at a range of about one hundred yards, meaning that it was impossible to facilitate emotional distance from destructive acts.[v] Metzner’s work reveals the internal struggle that countless soldiers battled with, as the work of killing marked a significant departure from their understandings of themselves as human beings and Christians.[vi] His watercolour is not a visual assault on the Confederate soldier, but a terrifying representation of the fate that frequently befell the victims on both sides of the conflict.

[i] Rev. A. M. Steward, Camp, March and Battle-Field; or, Three Years and a Half with the Army of the Potomac (Philadelphia, PA: Jas. B. Rodgers, Printer, 1865), pp. 280; 188

[ii] George Oscar French, ‘letter, to Dear friends, Camp on the Chickahominy, Near Cold Harbor June 10th;’ ‘letter, to Dear Father, Hospital, Annapolis, Sunday morn. August 28th 1864,’ George Oscar French Letters, Vermont Historical Society, http://vermonthistory.org/research/research-resources-online/civil-war-transcriptions/george-oscar-french-letters

[iii] Michael A. Peake, Blood Shed in this War: Civil War Illustrations by Captain Adolph Metzner, 32nd Indiana (Indianapolis, IN: Indiana Historical Society Press, 2010), pp. 2

[iv] Wirt Armistead Cate, ed., Two Soldiers: The Campaign Diaries of Thomas J. Key, C.S.A., December 7, 1863 – May 17, 1865 and Robet J. Campbell, U.S.A., January 1, 1864 – July 21, 1864 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1938), p. 182

[v] Drew Gilpin Faust, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (New York, NY: Random House, Inc., 2008). For more on the destructive power of rifled weaponry, which caused 94% of Union casualties in the war, see Hess’ The Rifled Musket in Civil War Combat: Reality and Myth (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2008).

[vi] Orestes Brownson; Henry F. Brownson, ed., The Works of Orestes Brownson (Detroit, IL: Thorndike Nourse, Publisher, 1882-87), Vol. 17, p. 214

I am living history volunteer at Stones River National Battlefield. One of the most difficult things we face is conveying the true nature of what happened while surrounded by a beautiful landscape. This drawing is the most powerful depiction of the true cost of the battle of Stones River that I know of… its simple, pathetic honesty may be unique.

Mentzer’s drawning above & those in the Library of Congress are not the elaborate stick figure style typical of soldier drawings. His work is carefully observed, buildings are in proper perspective, the comic portraits spot on. He was not a naive amateur. If anybody knows of a good biographical source, I would like to see it.

I think your comments about Metzner are spot on Rhea. He really stands out amongst Civil War soldier-artists. The best and only biographical source I am aware of is Michael A. Peake’s ‘Blood Shed in this War’ (2010), but you might have already come across that!

No, I had not encountered his work until a few months ago. Finding work by a soldier who was also a trained artist is so rare. I am going to incorporate several of his images into my presentations.

As an artist and history geek, I am eagerly looking forward to more posts in this series! What a fascinating idea for a book. I don’t think I’ve seen this subject covered – in this way – before.

As and artist and history geek myself, I eagerly await the next installments! This is also a great subject for a book. I don’t think I’ve seen Civil War soldier art looked at in this way before. Thanks for posting this piece!

You should look at the rest of the file from Library of Congress online.

Thanks for the comment, it is much appreciated. The majority of works on soldier art are published compilations of their wartime images, interspersed with their textual records of the war. There are some brilliant books that exhibit some amazing source material but I’ve always found it frustrating that they don’t delve further into greater analysis of the images. I’m currently working on a PhD that seeks to weave together the numerous collections of war art produced by Civil War soldiers (paintings, sketches, photographs, cartoons, etc.), and to view them as statements about the war experience, rather than just pictures of it. It may well be a book in the future!

I was allowed the great honor of working with this artwork through a gentlemen’s agreement with Metzner descendent E. Burns Apfeld. When arranged chronically, the collection exists as a visual diary of what the 32nd Indiana endured during the first three years of war. The original manuscript married this art collection with a 79-image photograph collection Metzner amassed during his service. Due to the hefty size of the manuscript, much more of the text and a majority of the photographs were eliminated. Each art sample generated a story of its own, often augmented with newspaper soldier letters, reports or diary entries. “Cozy Corner” had a matching account one officer provided to two German language newspapers of the era. The following comes from the original manuscript as a caption to the image: During the early stage of the overwhelming Confederate assault on the Union right, Colonel Erdelmeyer managed to retain control over 200 men of the 32nd Regiment Indiana Infantry as a fighting force that united with fragments of the 15th and 49th Ohio Regiments, creating a defensive line on the other side of Overall Creek with the 89th Illinois. Captain William George Mank later wrote to the Täglicher Louisville Anzeiger declaring, “The position of the 32nd Ind. Regt. was a very difficult one. We barely had a [split-rail] fence for protection and were nearly run over by the fleeing [men] and by the run away artillery horses, but we held our position and fired volley after volley at the enemy until everyone behind their front pulled back, and only after they saw that everything was lost did the valiant Germans have to retreat with large casualties, still escorting rescued cannon. The 32nd Regiment halted often during its retreat and fired effective volleys at the enemy, just as the cannon that still were with us did their best.” In a second letter to the editor of the Indiana Staatszeitung (State Journal or Gazette), Captain Mank described the stand behind a fence and having Rebel infantry close in tightly, but proclaimed “Our number was small; however, each one wanted to sell his life as dearly as possible…Lt. Col. Erdelmeyer who led our regiment, distinguished himself through his bravery, always at the head, he assembled his men, and led them again toward the enemy. Had all the principal officers done their duty on this day like Erdelmeyer, we would not have so many comrades to mourn.”

I am coming in late on your post, but so glad I discovered it. I am an amateur artist and Civil War history buff–for over 60 years. I have been interested in soldier-artists (as well as a few sailor-artists) of the Civil War. I have found some targeted references and bio information on about 50 artists, including images of their works. James, have you completed your PhD research, and possibly a book on the subject?