“Little Photography in Jeffdom:” The Decline of Photography in the Civil War South

In 1862 Humphrey’s Journal of the Daguerreotype and Photographic Arts boasted that “The Photographic Art down South has completely died out in consequence of the war.”[i] Though an obvious overstatement, considering that southern photographers operated throughout the war, the journal was observing the decline of photography in the warring Confederacy. The exaggeration was echoed by Charles A. Seely a year later. Seely wrote in the American Journal of Photography in 1863: “There has been little photography in Jeffdom.… It is only in Charleston and perhaps Richmond that any photographs are made.”[ii] But northern observers had not always reveled over photography’s waning in the South.

Following the 1860 Presidential Election, Humphrey’s Journal mused on the South’s political and photographic future:

There may spring up another demand by-and-by from the South, for they will have to get melainotypes of their candidates for the Presidency of the Southern Confederacy, should our Glorious Union be so unfortunate as to be split in twain…[iii]

The writers anticipated that with the prospect of a forthcoming Confederate presidential election, photography might experience a surge in the South as the candidates employed imagery in their bid for office. This had been the case in the 1860 U.S. election, in which photography had featured with the production of tiny tintype portrait badges of the competing candidates to be worn by their supporters. But this was not the result, hindered in part by the lack of a vigorous two-party system of mass politics as found in the northern states. There were no political parties in the Confederate South, which dissuaded producers of ideological and political imagery from seeking profit in the fledging nation.[iv]

But the Confederacy’s difficult relationship with the photographic art was not caused singly by the lack of a two-party system in the South. The South had always lagged behind its northern counterpart in artistic creativity. The centres of the photographic art were found in the northern metropolises and included New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, whilst centres of the southern graphic arts were not able to influence the creative output of the Confederacy. Baltimore never seceded, whilst New Orleans fell to Admiral David G. Farragut’s Union fleet relatively early on in the war, on April 25, 1862.[v]

Photographic innovation occurred largely in the North. The tintype, a uniquely American form of photograph, emerged in Ohio.[vi] E. & H. T. Anthony & Company, the largest supplier and distributor of photographic supplies in the U.S., was located in New York City. Thomas Cooper de Leon, brother of the Confederate diplomat and propagandist Edwin, noted that the South “in all art matters… was at least a decade behind her northern sisterhood.” Those artists who could afford to received their creative education in the North and “almost invariably settled in the northern cities.”[vii] Photography took many of its creative cues from the traditions of painted portraiture, and many artists practised photography alongside their canvas-based endeavours. The migration of southern artists to the North also hindered Confederate photography.

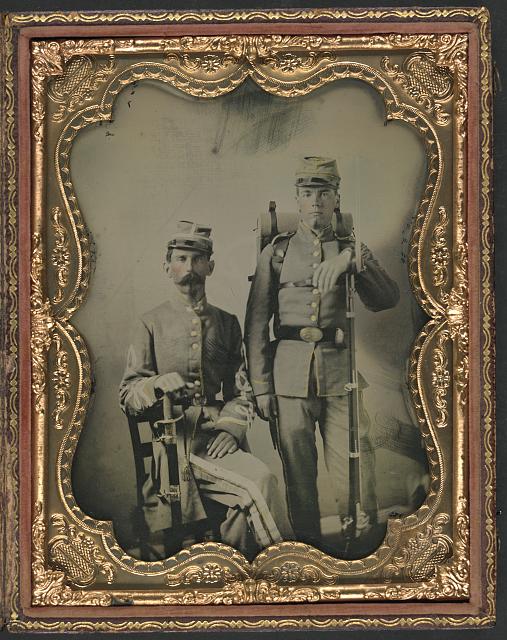

With the war’s outbreak southern photography declined rapidly. Chemicals for photographic development, such as silver nitrate, collodion, and cellulose nitrate had priority for employment in the army over the photographic studio. They were components in medicine and munitions production.[viii] Moreover, the symbolic props and backdrops so common in photographic portraits of Union soldiers were not as easily attainable in the Confederacy.[ix] In December 1862, the Southern Illustrated News admitted a shortage of models and asked its readers to submit photographs of Confederate generals to base the newspaper’s engravings on.[x] Those images that did appear in its pages were mostly reproduced from outdated photographs or even images copied from northern newspapers.[xi] The struggle of a major southern newspaper based in the Confederate capital to obtain recent photographs of Confederate military heroes is illustrative of photography’s dearth in the South.

But ultimately the claims that photography had “died out” in the South, or that it was “only in Charleston and perhaps Richmond” that any photographs were made, were obviously fiction. Such assertions are disputed by the vast archive of Confederate photographic portrait imagery of southern statesmen, soldiers, and civilians that remain in a multitude of archives, such as those held by the Museum of the Confederacy and in the Library of Congress’ ‘Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Portraits.’ There is no doubt that the prominent southern photographer, George S. Cook of Charleston, was producing some of history’s first combat photographs in September, 1863. The South made its contributions to early photographic history, regardless of its disadvantages.

Confederate soldiers observed the employment of photography in the South. B. M. Zettler of the 8th Georgia recalled how the 21st Oglethorpe Light Infantry became the centre of attention for the ladies of Richmond, noting that “more than one Oglethorpe took with him when he left for the front a tiny photograph or a card with a name on it.”[xii] Sam Watkins of the 1st Tennessee reflected on how he had carried his sweetheart’s image alongside a “braid of her beautiful hair” during the war.[xiii] They were as important cultural items to southerners as they were northerners, even if their numbers were limited in comparison. Regardless, the assertions of northern photographic operators suggest the real scarcity of photographers in the Confederate South. Wartime demands inhibited the South’s photographic culture. Photographic images were not the widely-accessible cultural items they were in the North. Confederate photography lagged behind the North on both the individual and national scale.

[i] Humphrey’s Journal of the Daguerreotype and Photographic Arts, v. 13, Jan. 1, 1861, in Smith and Tucker, Photography in New Orleans, pp. 104-105, in Keith F. Davis, ‘A Terrible Distinctness.’, in Martha A. Sandweiss ed., Photography in Nineteenth Century America (New York, NY: Harry N. Abrams, 1991), p. 147

[ii] Charles Seely, “Editorial Department,” American Journal of Photography 6, no. 6 (1863), p. 143, in Welling, Photography in America, in Janice G. Schimmelman, The Tintype in America, 1856 – 1880 (Philadelphia, PA: American Philosophical Society, 2007), pg. 57

[iii] Humphrey’s Journal, v. 12, Dec. 1, 1860, p. 9, in Robert Taft, Photography and the American Scene: A Social History, 1839 – 1889 (New York, NY: Dover Publications, 1938), p. 158

[iv] Mark E. Neely, Jr.; Harold Holzer; Gabor S. Boritt, The Confederate Image: Prints of the Lost Cause (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), p. 6

[v] Neely, Jr.; Holzer; Boritt, The Confederate Image, p. 3

[vi] Schimmelman, The Tintype in America, pg. 37

[vii] Thomas Cooper de Leon, Four Years in Rebel Capitals: An Inside View of Life in the Southern Confederacy (Mobile, AL: The Gossip Printing Co, 1892), pp. 299-300

[viii] Schimmelman, The Tintype in America, pg. 57

[ix] Jeff L. Rosenheim, Photography and the American Civil War (New York, NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013), pp. 47; 128

[x] Southern Illustrated News, December 13, 1862, p. 2, in Neely, Jr.; Holzer; Boritt, The Confederate Image, p. 26

[xi] Jennifer Raab, ‘Painting and Illustration.’, in Maggi M. Morehouse & Zoe Trodd, eds., Civil War America: A Social and Cultural History (New York, NY: Routledge, 2013), p. 222

[xii] B. M. Zettler, War Stories and School-Day Incidents for the Children (New York, NY: The Neale Publishing Company, 1912), p. 46

[xiii] Samuel R. Watkins, “Co. Aytch,” Maury’s Grays, First Tennessee Regiment; or, A Side Show of the Big Show (Chattanooga, TN: Times Printing Company, 1900), p. 153

Excellent article and insight into a sometimes overlooked aspect of the war. It reminds me of the dearth of photographic images from the western theatre as opposed to the eastern. There are some of course, but not many comparable to the number made in the east.

Fascinating information. I really enjoyed the article, especially since I recently had a tintype taken for the first time and I’d been curious about photographs in the South. Do you know if photography was “part of” the Antebellum culture in the South? Were folks who could actually afford it more likely to have a painted portrait made, rather than a photograph? (Or were painted portraits more a Colonial/Jeffersonian Period preference?)

Hi Sarah, I’m glad you enjoyed the article. The tintype process is a wonderful one to say the very least, and gives you a real appreciation of the significance of these unique portraits during the war.

I believe photography was very much apart of antebellum southern culture, though limited in comparison the North. Prior to the war, the South had access to much of the visual culture produced by the North such as photographs, illustrated newspapers, patriotic ephemera, etc. Northern producers of photographic supplies were selling their goods South. In fact, in the initial stages of the conflict some northern illustrated weeklies were reporting very carefully on the unfolding crisis in order to retain their southern subscribers, and some producers of patriotic ephemera in the North were making Confederate stationery for sale in the South.

Though painted portraits (and silhouette portraits) were employed by southerners in the antebellum era, the advent of photography provided a new and novel form of visual self-representation that Americans clamoured for. The NY Daily Tribune estimated in 1853 that 3 million photographs had been made in the U.S. (though it doesn’t offer regional figures, this is a tremendous amount [considering photography’s relative inaccessibility in the early 1850s]) and gives the impression of a “photomania” unfolding in the U.S. As innovations in the process made photography more accessible, lower social classes were able to get their picture taken for as little as 25c. Sam F. Simpson recorded in 1853 that he had taken his camera by boat down the Mississippi River, stopping at around 50 landings and taking over 1,000 photographs. George S. Cook recorded enjoying a booming photographic business both prior to, and during, the war in Charleston, S.C. I’ve seen an account of a Confederate officer using a photographic wagon abandoned after 1st Bull Run as his headquarters. He writes of how hundreds of Confederate soldiers surrounded the van pleading to have a picture taken: though it speaks of the scarcity of photography in the South, I think it shows a familiarisation with photography that would have had its roots in the antebellum era.

Long story short.. it’s difficult to know for sure! I would argue that photography was part of southern antebellum culture, but limited in comparison to the North. With the war and the subsequent severing of ties with the North, transportation limitations, manpower constraints, the devaluing of practically all non-martial skills, the blockade, and the uses of photographic chemicals in war/medicine production, photography was hit a serious blow in the South and thus, we have a far more limited archive of southern Civil War photographs to draw upon today.

Thanks for the extra information. It gives me hope that someday, somewhere, I’ll find photographs of some of the Virginia families I’m researching.

That estimated record of 3 million photographs in 1853 is amazing! I had no idea photography was so prolific at that point in history.

always looking to learn . thank you James